A Loss Only Mariners Baseball Could Cure

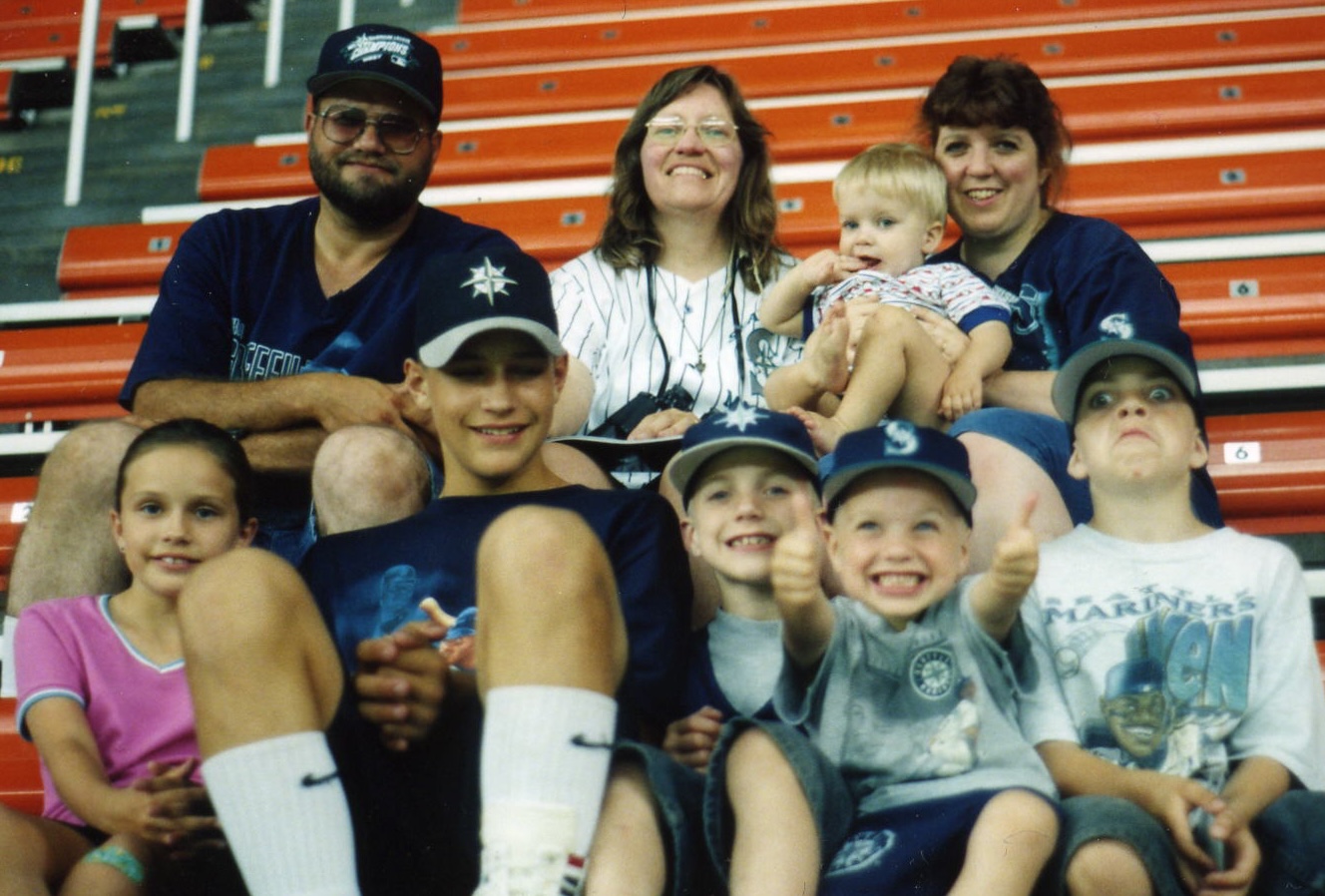

I am not a Mariners fan. I have never been a Mariners fan. I have no intention of becoming a Mariners fan. But the first major league game I ever attended was, in fact, a Mariners game. Here’s what I remember from that game: It took place on July 30, 1998 in the Kingdome. It lasted 17 innings and stretched into the following day. We were sitting on metal bleachers, pretty high up. I knew that some of the big names on the Mariners that year were Ken Griffey Jr., Alex Rodriguez, Randy Johnson and Jay Buhner. I spent most, if not all, of the game reading a book because I absolutely did not care about baseball. That’s it. I know that isn’t much, so here’s some photo proof that I was actually there:

I’m the nine-year-old girl on the left and the only one not wearing Mariners gear. Again, I have never been a Mariners fan. The kid next to me is Roger, my 13-year-old brother (yes, that oversized manchild was really only 13, I triple-checked the math). He was the reason we were at the game and the reason I could name a whopping four Mariners.

Roger started playing baseball before my brain started making conscious memories, so for me, an obsession with the game was a core component of his identity. Even though we lived in northwestern Montana, he managed to play organized ball roughly six months out of the year. My dad got roped into coaching his teams pretty early on. At some point my mom took on official scorekeeper duties, and as if that wasn’t enough, all three of them got into umpiring as well. I truly cannot overstate how much of my childhood was spent at the ballpark, sitting on wooden bleachers with my butt going numb and a book in my hand.

I hadn’t thought much about that game, or how much my brother loved the Mariners, in a good long while. But then on the final weekend of the 2025 regular season, I was at T-Mobile Park, standing on the field during batting practice, waiting to talk to Andrés Muñoz for an article. I was watching Ichiro Suzuki shag fly balls in right field, as he often does during Mariners BP.

I still find standing on a big league field incredibly cool even though I’ve done it plenty of times now; I hope it never stops feeling incredibly cool. But on that day, it occurred to me that I wasn’t just standing on a big league field, I was standing where my brother’s favorite team plays, watching that team take BP and watching one of that team’s legends jog around in the afternoon sun.

Though Roger and baseball are welded together as a single entity in my mind, I have such a glut of baseball memories associated with that I rarely ever think of him as a Mariners fan. But watching Ichiro patrol the outfield, looking basically the same as he always has, shook that memory loose. I wasn’t just doing a cool baseball thing, I was doing a cool baseball thing that would make my brother even more jealous than all the other cool baseball things I’ve done.

This is the part where I have to explain why I had forgotten that my brother was a Mariners fan. He didn’t stop being a fan, but he did stop existing in the mortal plane. He died in March of 2002 at the age of 17. I was 13 at the time, and even though it’s been over 20 years, I still haven’t figured out a “good” way to introduce this part of my family history when, say, someone innocuously asks if I have any siblings. No matter how I phrase it, the conversation winds up cloaked in several layers of discomfort. They’re uncomfortable about dredging up a painful part of my past. I’m uncomfortable about my honest answer to their question making them feel guilty for asking, even though they couldn’t have known. Maybe they’re uneasy with death as a concept because no one close to them has died. I’m self-conscious about seeming heartless because I’m not at all uneasy about death as a concept. I could soften the language I use, but it doesn’t make the reality any softer. Disguising death in phrases like “passed away” doesn’t make death any easier to grapple with. If anything, refusing to talk about death using precise language makes it feel even more unfair when death inevitably comes calling. I’m not an authority on any of this, but after a forced confrontation with mortality at age 13, I do feel entitled to be straightforward and maybe even a little glib about my dead brother. I’m sure he wouldn’t mind, so I hope you won’t either.

By early 2002, it had been four years since we’d sat together in those bleachers at the Kingdome. The 2001 season had concluded a few months prior. Y’know the one where the Mariners won 116 games? Prior to this year, that 2001 season was the last time the M’s had reached an ALCS. So as I spent that September afternoon watching BP, I thought about Ichiro, who got his first and only playoff experience with the Mariners as a rookie in 2001, and I thought about Roger, who got his first and only experience attending a Mariners game on that 1998 trip to Washington.

I confess, I do have one other memory from that first game. At some point during one of the eight extra innings played that night, I decided to briefly engage with the game. I asked Roger if I could have a turn with the binoculars we’d brought. He begrudgingly handed them over, but mere moments into my survey of the stadium, he was pounding on my shoulder, wanting to know who was warming in the Mariners ‘pen. He was hoping that if the game went long enough, Randy Johnson would be pressed into service. He was so excited at the thought of seeing Johnson pitch that he couldn’t simply wait for me to get bored and relinquish the binoculars back to him (which would have taken like two minutes, tops); he had to know immediately. That’s how stoked he was about this game. We went to another game the following night, but that was it. I’ve now been to more games than I can count. He’s been to two.

When I tell people my only sibling died when we were teenagers, no one ever knows what to say, which is fine. The next time someone finds something comforting to say about the death of a loved one will be the first. But here’s what I’ll say about the experience. It sucked a whole lot, and it continues to suck. And the suck never really stops, you just learn to manage it better. The thing about the grieving process is that it’s not actually a process for getting over the pain of a loss, as we’re often led to believe. It’s more a process for learning to manage the pain of that loss. Because it’s never going away.

So I adapted to a version of life without my older brother and one with way less baseball. At least at first. For over a decade, I had no idea what was happening with the Seattle Mariners or any other big league team. And why would I? Baseball was never my thing. That was his thing.

As it turns out, baseball is very much my thing. But as the obnoxious little sister, who existed to push buttons and be a relentless contrarian, I had to come to it on my own terms. Later, as a teenager who won calculus competitions and wanted to be a writer or maybe a dancer, but probably a writer, I didn’t think baseball had anything for me. No one told me about all the storytelling between the white lines, or about the rhythm and grace of infield defense, or how this sport has so much math. Or maybe they did, but I was too much of a stubborn nonconformist to listen. I saw my whole family doing something and immediately decided that I needed to go do something else.

Eventually I found my way to baseball. I was living in Baltimore for grad school and the 2012 Orioles got their talons in me. It was the narrative resonance of that team and the visual art on the field that first drew me in. But it wasn’t long before I got hip to the nerdy stuff too. And the nerdy stuff was my entry point to working in baseball. Over my seven years working in and around the game, first as a research analyst on the team side, then analyzing data for MLB The Show and writing for FanGraphs, I’ve thought often about how Roger and I both developed a love for this sport, but each in our own distinct way. For a long time, I dismissed the whole endeavor in the name of individualism, but now that I’m here, I’m extremely grateful to have something that functions as such a strong point of connection to someone who is no longer physically present.

As I’ve adapted to the pain of his absence, the part that hurts the most is the adult phase of sibling friendship that we never got to experience together. The steadfast presence of baseball provides a medium to channel that relationship in a different form, but it’s not always easy. And that’s why I have to even more explicitly acknowledge this specific Mariners squad. In over two decades, I have never felt even slightly compelled to write about my brother’s death, even though people write about death all the time, and maybe some reader experiencing something similar would have felt less alone. I just couldn’t figure out a way to do it that didn’t reek of cringe. But as I covered their home playoff games, this Seattle team poked and prodded at my feelings so many times that it finally triggered enough genuine emotion to write something other than the usual stew of rote clichés.

It helps that this isn’t just any iteration of my brother’s favorite team. As previously noted, the 2025 Mariners are the first Seattle squad to make the ALCS since 2001 — the last season he was around for — and there were echoes of the 2001 team everywhere you look during this year’s playoff run. It’s not just Ichiro shagging fly balls during BP. Edgar Martinez, iconic DH for the 2001 team, who also has his name on a street outside the stadium, now serves as the Senior Director of Hitting Strategy, meaning he’s back in uniform on a nightly basis (Martinez was also on the 1998 team and had three hits during that 17-inning game). Prior to ALDS Game 2, I found myself sharing an elevator with Jay Buhner, outfielder and alumni of the 2001 squad, who was on hand to throw out the first pitch and was in the building for most, if not all, of the team’s home playoff games this year. Lou Piniella, Seattle’s manager in 2001, handled first pitch duties for ALDS Game 1, throwing to his team’s catcher and current manager, Dan Wilson. Oh yeah, the 2025 Mariners are managed by literally Dan Wilson.

I don’t remember if Roger ever regaled me with the stats on the back of Wilson’s baseball card, but as a fellow catcher, I’m sure he studied Wilson carefully. Roger didn’t just catch though. He also pitched. And played third. And made for a useful first baseman when the kids on the left side of the infield needed a nice big target to throw to. He had the athleticism to play anywhere he was needed, but he mostly pitched and caught. I can’t give you a full scouting report because I was a little kid who wasn’t trying to know anything about baseball. But I am confident he threw very hard. While catching, he frequently threw out attempted base stealers at second without bothering to stand up. He felt his arm was more accurate from his knees, and his throws beat the runner even without the power from his lower half. (Now imagine him excitedly explaining this at the dinner table and me rolling my eyes with a mouthful of mac and cheese, and you’ll understand our sibling dynamic.)

But in the late ‘90s, it didn’t matter what position a kid played, everyone’s favorite player was The Kid. Roger was no exception. As I sat in the press box before ALDS Game 5, I watched the video board as the image of the rear fender of a car with a license plate that read “24Ever” appeared on the screen. It doesn’t take a Mariners fan to figure out who that car belongs to. As Ken Griffey Jr. took the field in a black convertible emblazoned with teal flames, all I could think about was the giddy energy of the 13-year-old kid who sat next to me on the metal bleachers all those years ago, straining to get a glimpse of his idols. And despite not sharing his zeal for Seattle baseball, I let that giddy energy take hold within myself. At least for a few minutes. Feeling I owed it to him, to experience that moment through his eyes.

There have been other times where I’ve made it a point to do the things he wasn’t able to, but I can’t claim that I chose to work in baseball to honor his memory. I’m far too stubborn to let anyone else’s dreams dictate my career path. And baseball wasn’t even my first choice. I test drove several other options before sticking with this one. Part of my initial apathy toward baseball stems from my own competitive spirit. If I’m not convinced I can win, I don’t want to play. Especially not if my opponent is my equally competitive older brother. So it took finding the parts of baseball I could win at to really pull me in. And now I’m in the win-win scenario of getting to gloat for making it further in the sport than he did while getting to carry the family baseball legacy in his stead.

Which brings me to the star of this year’s Mariner squad: Cal Raleigh. A catcher like my brother, but also someone who, like me, carries a family baseball legacy. During the postgame press conference following ALCS Game 5, Raleigh was asked about the significance of his jersey number. As I listened from my seat in the second row of the interview room, I probably I shouldn’t have been surprised to learn that here was yet another thread tugging at my emotional connection to this team. After all, death is a universal experience we all unenthusiastically share. But even still, I felt the Jenga tower in my brain start to wobble as I listened to Raleigh explain that he wears no. 29 in honor of his uncle, who passed away at a young age. It happened well before Cal was born, but he emphasized the outsized impact his dad’s brother had on their entire family. It’s yet another unexpected connection to this team, knowing that Raleigh understands what it’s like when a baseball family loses a ballplaying brother, that he has a ballplaying brother of his own, and that he too, “almost [by] coincidence” (as he noted in his answer to the question) wound up honoring that legacy with his own career by wearing no. 29 on his back.

I know my brother would be equal parts annoyed and proud of everything I’ve accomplished in baseball. If you paused in confusion wondering why he’d be annoyed, it goes back to the whole competitive sibling rivalry thing. We never talked about it, but I’m sure he dreamed of making it to the big leagues one day. Instead, his little sister, who grumbled about spending all summer at the ballpark, is the one with a National League Championship ring with our family name etched on the side. So yeah, he’d be annoyed that I beat him at his own game. But he’d definitely be just as proud too. Just like he was proud when my dance team won at nationals and he watched me walk off the plane carrying a trophy twice as big as anything he’d won playing baseball.

And though I can imagine how he’d react and what our relationship would be like now, I am sad that I haven’t gotten to experience those reactions firsthand or share in any of baseball’s highs and lows with him. But the 2025 Seattle Mariners opened up a portal that brought me closer to that version of reality than I thought possible. Baseball, like life, is marred by loss. So despite a disappointing end to the season, the Mariners did what all great baseball teams do. They furnished the type of shared experience that connects people and bonds them together, both in the here and now and across the decades. For that, I owe them one. So for the first (and probably last) time ever, I leave you with a hearty, GOMS!

Kiri lives in the PNW while contributing part-time to FanGraphs and working full-time as a data scientist. She spent 5 years working as an analyst for multiple MLB organizations. You can find her on Bluesky @kirio.bsky.social.

This is lovely. Go M’s