Side by Side: Liriano and Hernandez

They say that 50 is the new 40, but I like to say that Francisco Liriano is the new Felix Hernandez. Seattle’s Hernandez made a splash in his major debut last year, going 4-4 with a 2.67 ERA and displaying great velocity, control and the ability to keep the ball on the ground. Sadly, he has not performed as well in 2006, though his long-term potential remains intact.

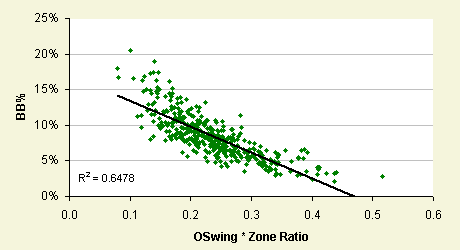

This year, Minnesota rookie Liriano is even better than Hernandez was last year, with a 9-1 record and a 1.99 ERA. Like Hernandez, Liriano strikes out batters, doesn’t walk them and keeps the ball on the ground. But some of you may have forgotten that Liriano actually made his debut last year, when his ERA was very similar to Hernandez’s 2006 ERA (admittedly, in only 23.2 innings pitched). In fact, the two youngsters over the past two years form an “X” on this ERA graph:

Two pitchers, so similar in stuff, have been contrasts the past two years. Let’s take a closer, graphical look at some of their components to see if we can spot the key differences between them last year and this year.

Both pitchers are premier strikeout pitchers, though Liriano is particularly impressive. He leads the major leagues in strikeouts per nine innings and Hernandez is 14th.

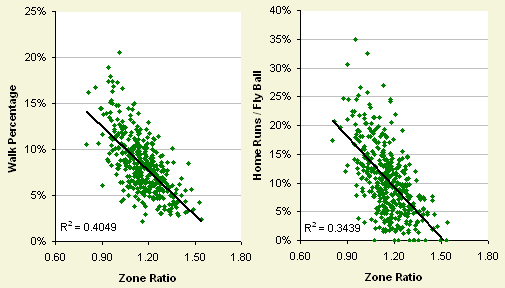

Both pitchers also have great control — Liriano has particularly improved his control this year, a key to his great start…

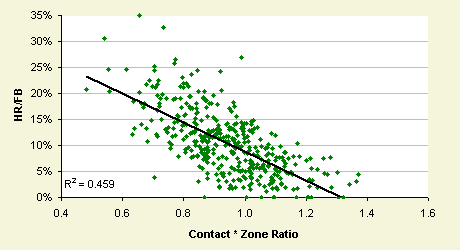

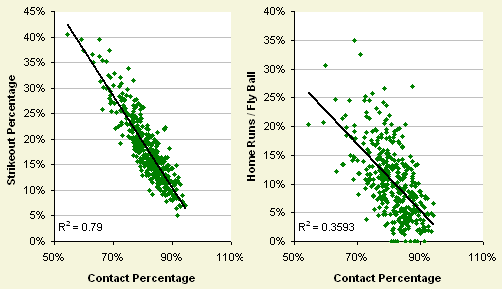

In general, pitchers have the most control over strikeouts and walks — after that, things start to break down a bit. For instance, a big difference between these two young studs in 2006 is the last of the “three true outcomes,” the home run. Hernandez and Liriano have have formed another “X” on either side of the major league average, which partially accounts for Liriano’s improvement and Hernandez’s decline.

Once a ball is hit in play, a pitcher is dependent on his fielders for help. Liriano’s fielding support has remained around the major-league average, but Hernandez’s hasn’t, as you can see in this graph of each pitcher’s Batting Average on Balls in Play.

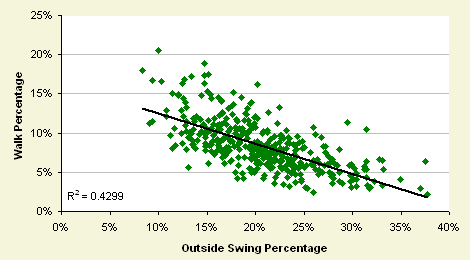

But the most dramatic difference between the two phenoms the past two years has taken place on the basepaths. Take a look at the percentage of baserunners each pitcher has left on base this year and last:

Felix’s LOB% has gone down, and Liriano’s has gone WAY up. Now, this change isn’t entirely random; pitchers with a 1.99 ERA will almost always have an impressive LOB%. But it’s one more part of the equation for each pitcher, which might be summarized as follows:

Hernandez in 2006: more home runs, more hits falling in, more baserunners scoring.

Liriano in 2006: improved control, fewer home runs, fewer baserunners scoring.

These trends mean next to nothing regarding each one’s long-term promise. In fact, the most meaningful difference between the two is one I haven’t graphed, age. Hernandez is two-and-a-half years younger than Liriano, which makes his potential long-term career a bit brighter.

Here are a couple of bonus graphs, the batted ball types for both pitchers. First up is Hernandez’s, and you can see that he hasn’t been as strong a groundball pitcher as he was last year (Note: the green line is the percent of batted balls that are groundballs, the blue line represents the flyball percentage and the red line represents the percentage that are line drives):

Finally, here is Liriano’s graph. The key is that he is getting batters to pound the ball into the turf as often as Hernandez. In fact, the two kids rank fourth and fifth in highest groundball percentage among all league pitchers — an extremely impressive stat.

Remember that combination: groundball pitchers with 95-100 mph fastballs and great control. You can’t beat it.