Jose Altuve Doesn’t Need Exit Velocity

Jose Altuve has been doing the same thing for a long time now. The 35-year-old Astro is closing in on 250 career home runs despite the fact that he’s never possessed the look, or even the swing, of a traditional slugger. Altuve has never hit the ball hard and has always chased a bit more than you’d like, but he’s excellent at making contact, which helps him avoid strikeouts, and he’s excellent at pulling the ball in the air, which helps him make the most of that contact. Altuve has ridden those pulled fly balls to a career 114 SLG+ and 101 ISO+. If we start in 2015, the beginning of the Statcast era and the year he really started to focus on lifting and pulling, those numbers are 119 and 113. This year, however, for the first time, I’m genuinely starting to wonder how Altuve is still doing it.

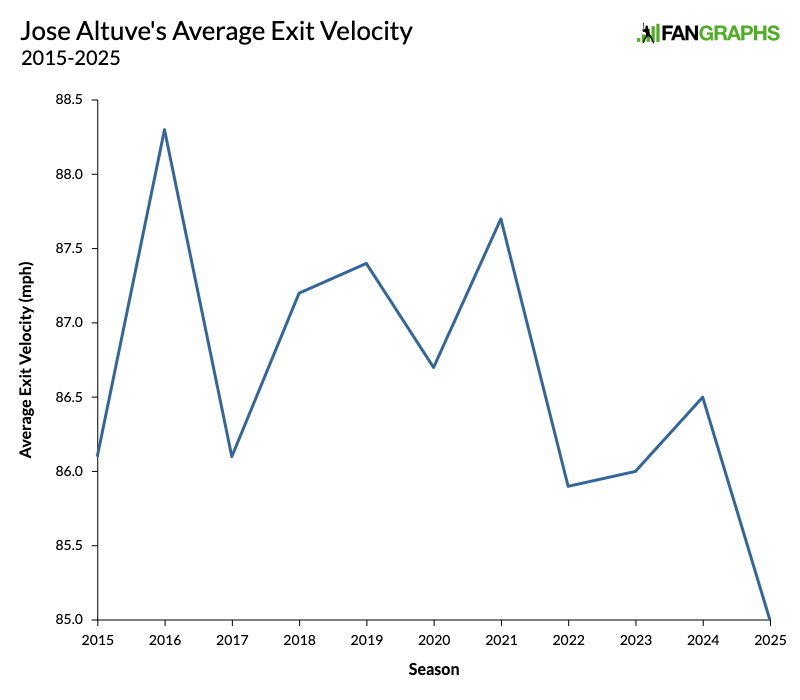

Altuve is running an average exit velocity of just 85 mph. Here’s what that looks like in the context of his career. It’s the lowest mark he’s ever put up by nearly a full mile per hour, and it’s 1.5 mph off the average he put up just last year:

Those numbers look even more stark when we put them in the context of the rest of the league. Altuve is running the second-lowest average exit velocity among all qualified batters. Think of any slap-happy contact hitter – Luis Arraez, Jacob Wilson, Sal Frelick, Geraldo Perdomo – Altuve has a lower average exit velocity than all of them. But like clockwork, Altuve is still running a 120 wRC+ and batting .280. With 19 home runs, he’s on pace for 27, the highest mark he’s put up since 2022. Altuve is still lifting and pulling, lifting and pulling, making contact, avoiding strikeouts, rinse and repeat, even though his contact quality has dropped to about as low as you can possibly imagine.

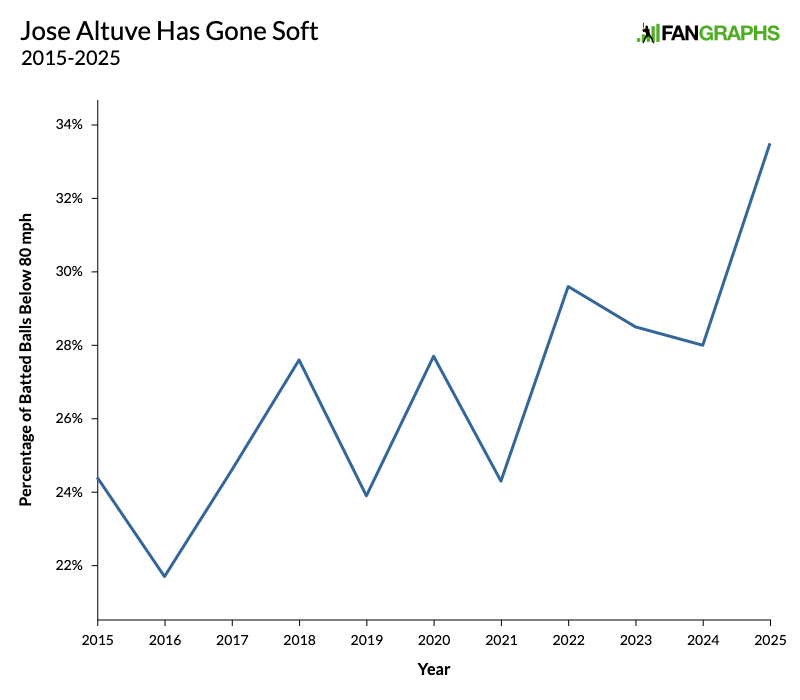

The most important context here is Altuve’s 90th-percentile exit velocity. At 101.5 mph, it’s actually higher than the 100 mph he put up last season, but it’s still the third lowest of his career. Among qualified players, it puts him in just the 12th percentile. When a player has a lower average exit velocity but a similar 90th-percentile exit velocity, it means that their top-end power hasn’t changed; they’re just mishitting the ball more often, trading medium contact for weak contact. The numbers bear that out. On balls that aren’t hard-hit, Altuve’s average exit velocity is 78.1 mph, the lowest mark of his career since 2015. Sports Info Solutions also tracks soft-hit rate, and Altuve’s is 20.6%, the highest since his partial rookie season in 2011. Here’s the best way I can show this to you. The graph below shows the percentage of balls in play that leave Altuve’s bat below 80 mph. Until this season, he had never reached 30%; he’d only surpassed 28.5% once. He’s now at 33.5%:

The advanced bat tracking numbers see the same thing. Altuve’s squared-up rate is down from last season. His average bat speed is holding steady, but it’s slightly faster if you only look at pitches over the heart of the plate, because he’s meeting the ball two full inches further out in front than he did last year (and bat speed increases throughout the swing). In other words, Altuve seems to be getting started earlier in order to meet the ball even further out in front to maximize his lift-and-pull game. At 56.3%, Altuve is running the highest pull rate of his entire career, and he ranks second among all qualified players. He’s tied with Nolan Arenado, another mid-30s lifter-puller, for the highest popup rate among qualified players.

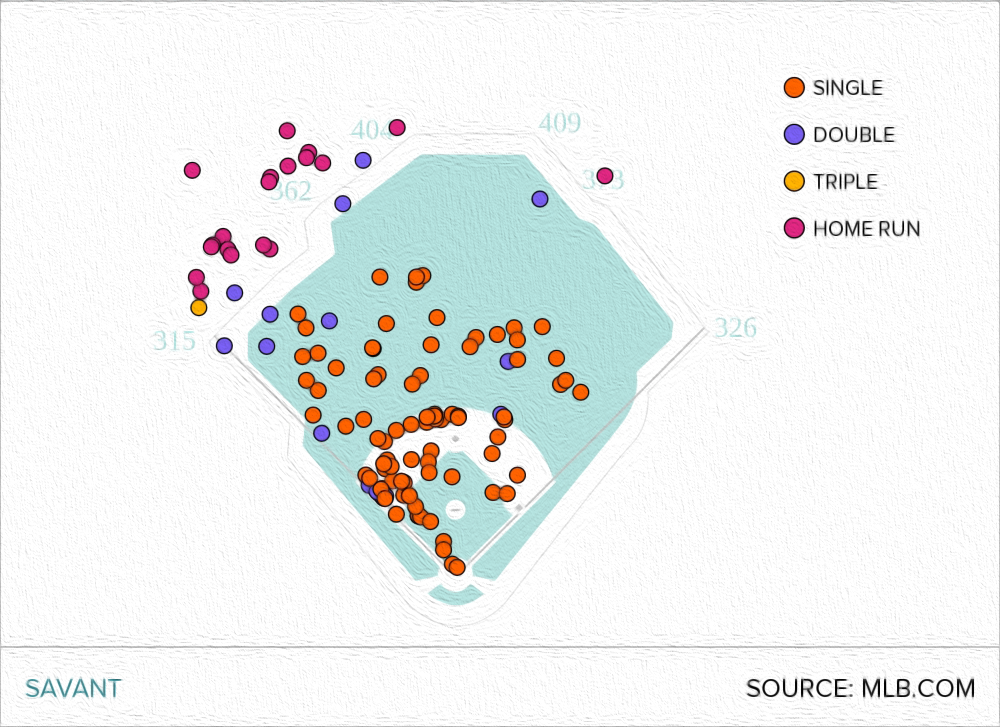

Over the course of his entire career, Altuve’s lopsided spray charts have been works of art. He’s capable of spraying the ball all over the field, but he only hits it hard enough to do damage to the pull side. When you just look at the base hits, the asymmetry is jarring, and this season’s chart is shaping up to be a pointillist masterpiece. He’s hit just one opposite field home run and hasn’t managed to blast a base hit over the right fielder’s head once. It’s a brilliant use of negative space:

I’ve been driving at a familiar narrative here. It’s the story of a player who’s compensating for a slowing bat. Altuve is still hitting well and is still capable of hitting the ball as hard as he did before, but he has to cheat more and more to do so. He’s moved back in the box a bit. He’s getting started earlier so he can meet the ball further out in front, which has caused one of the highest whiff rates of his career and more mishits. It still works because Altuve still makes a lot of contact and is excellent at optimizing it.

To be clear, I don’t know whether that’s what’s actually going on. Altuve could be compensating for some slight injury, or he could have just decided that this is how he wants his swing to look now. He’s also revamped his batting stance, starting even more open this year than he has in the past. But an older player compensating for a slower swing certainly feels like the simplest answer. Altuve is still making it work. He no longer looks like the guy who ran a combined 144 wRC+ from 2016 to 2023, but he’s still a productive hitter on a contending team. I would love to be wrong. Altuve isn’t a typical player for so many reasons, and there’s little he could do that would surprise me. He’s still just one season removed from a 154 wRC+. But if this is what the beginning of the end looks like, then he’s starting his decline as gently as possible.

Davy Andrews is a Brooklyn-based musician and a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @davyandrewsdavy.bsky.social.

I haven’t watched the Astros this year, moreso asking the crowd: has Altuve really been THAT bad on defense this year?

As someone who watches them every day, I don’t think he’s been any less valuable this year than he was last year. So still bad, but I guess I don’t understand DRS painting him as significantly less valuable defensively with the position change. They strategically put him out there with ground ball heavy starters so he barely gets the ball hit to him (compare his chances to other LFs with a similar number of innings)

He certainly isn’t good or even average out there, and they’ve been able to DH him a lot with Alvarez hurt, but it’s tough for me to reconcile the -10 with so few opportunities to make plays

I would also like to know this. I don’t take DRS seriously because it is prone to extreme values but OAA also says he has been very bad in LF (although competent at 2B).

My instinct is that when I see a player with greater than +1 or -1 in OAA per 100 innings that (a) they probably aren’t quite that extremeunless you see it over a 800+ innings and (b) the direction is definitely negative and probably at the point where they shouldn’t play there anymore. You don’t get an OAA like that if you’re close to average out there.