Nick Allen and the Meritocratic Tyranny of the Batting Order

Nick Allen is definitely going to show up on my FanGraphs Walk-Off page. I’ve checked in on him a lot over the last month, but of the 1,664 stats on his player page (yes, I counted them all), I’ve really only been paying attention to one number. I just want to know how many plate appearances Allen has. The answer is 304, and that won’t do.

A month ago, I wrote about homerless qualifiers, the all-but-extinct subset of players who come to the plate often enough to qualify for the batting title – a minimum of 3.1 plate appearances per team game, or 502 over a 162-game season – without hitting even a single home run. At the time, Xavier Edwards was the only homerless qualifier left, but I didn’t believe in him – which is to say that I did believe he had the capacity to hit a home run. He did just that on July 12, blasting a 97.8-mph wall-scraper off Scott Blewett:

Allen was the player I believed in. When I wrote my article, he was just 13 plate appearances away from qualifying, and he was entrenched as Atlanta’s everyday shortstop with half the season left. He seemed like a lock to qualify and, if possible, struck me as even more certain to avoid hitting a home run. In the ensuing weeks, he has lived up to my not-particularly-wild expectations. He has started nearly every game, and he has only once hit a ball even as far as the warning track. Seriously, this is the closest he’s come to homering over the past month:

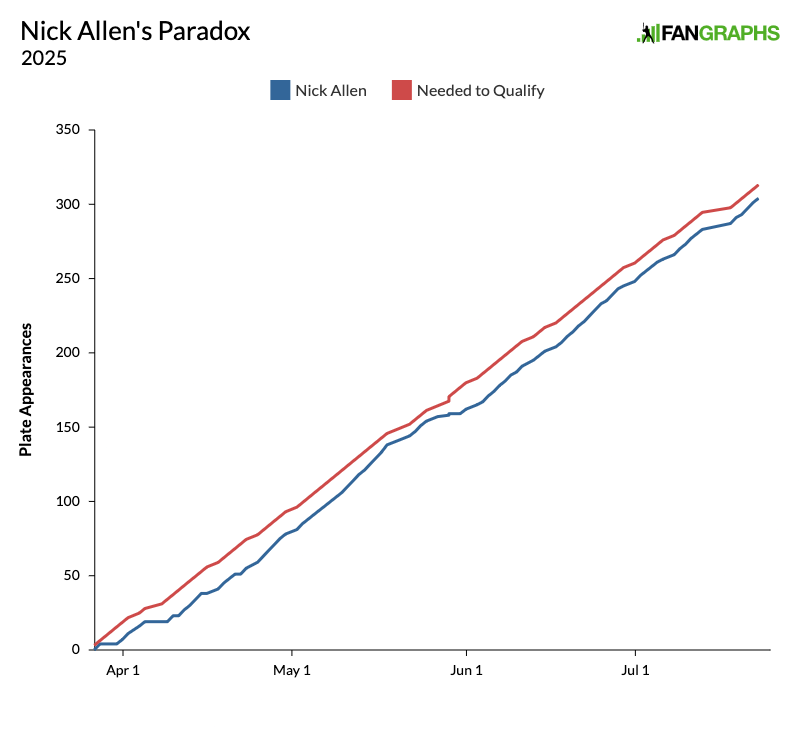

Here’s where things get tricky. It’s one month and 23 games later, and Allen is still 10 plate appearances from qualifying. How is it possible that he’s shaved just three plate appearances from his deficit over that time?

Allen is bumping up against the same problem as many would-be homerless qualifiers who ended up spitting the bit. With a 60 wRC+, he is the second-worst everyday hitter on the team (as well as the second-worst non-Rockie with at least 300 plate appearances). He’s batting ninth every day, and he’s bleeding plate appearances in the late innings. The day after my article came out, the Braves pinch-hit for Allen in the ninth inning. They pinch-hit for him again four games later, then one game after that, and four games after that, and one game after that, and three games after that — you get the picture here. Compounding the problem, the Braves are no longer a powerhouse offense, so they’re not turning their lineup over like they used to. Their 98 wRC+ ranks rank 18th, while their 3,839 plate appearances rank 19th.

Allen has only come to the plate five times in a game twice all season. It hasn’t happened since May. He’s averaging 3.3 plate appearances per game, and 3.2 since my article came out. Both numbers would be enough to qualify if Allen had started out as the everyday shortstop, but Orlando Arcia got nine starts early on. It’s not quite Achilles and the tortoise, but that late start has been enough to keep Allen on the razor’s edge all season:

On May 18, Allen got the gap down to eight plate appearances. He was right there, even though that also happened to be right around the time that his hitting completely bottomed out. On April 14, his wRC+ over the past 15 games was a nice, round 20, but the Braves didn’t have any better options. Then on May 29, a doubleheader set Allen way back. He got a rare rest in the first game, and in the second, he swung at an inside pitch that managed to hit him on the knuckles of his right hand:

The injury turned out to be minor. Allen only missed two starts, and the fact that the Braves had to start Luke Williams – who is not a shortstop – in his place emphasized just how much of a lock he had on the position. But all of sudden, he had just two plate appearances over four games and he’d dropped to 19 plate appearances away from qualifying. He’s been chiseling away over that total ever since, but slowly. If he keeps up the pace he’s run since June 4, the date that his deficit ballooned to 19 plate appearances, then he would qualify on September 2, after game 139. That leaves him very, very little margin for error. If he suffers another minor injury, if the Braves decide that they do believe in giving a player a day off once or twice a month, if they decide to give Luke Waddell a look because he’s running a 117 wRC+ in Triple-A Gwinnett, if Allen’s spot just happens to come up more often in those big, late-game situations that scream for a pinch-hitter, then he won’t qualify. It’s a rough business.

Choosing 502 plate appearances, 3.1 per team game, in order to qualify is perfectly reasonable standard. But we should also take a moment to note that it is arbitrary, and it’s arguably less fair than it initially appears. Baseball is a game in which everybody takes turns, but those turns are not distributed equally. Somebody has to bat first and somebody has to bat last. Nobody’s arguing that it’s time to overthrow the purported meritocracy of the batting order – at least not today – but I think we underestimate just how big an effect it has.

So far this season, batters have taken 2,710 more plate appearances from the leadoff spot than from the ninth. Based on those numbers, if you never missed a game and never got pinch-hit for, you’d average 4.6 plate appearances as a leadoff hitter and just 3.7 from the nine hole. That’s a difference of 0.88 plate appearances, and it leaves those batting ninth in a precarious spot. It means they need to play 135 games in order to qualify for the batting title, 26 more than the 109 required for a leadoff hitter. That’s a sixth of a season! They’re playing that sixth of a season, but they’re just not getting credit for it.

And that’s before we factor in the fact that the guys hitting ninth are down there for a reason. The league as a whole has a 79 wRC+ from the nine spot this season (a mark that you have to imagine Allen would at least momentarily consider committing murder to obtain for himself). That causes players who start the game ninth in the order to lose even more plate appearances in favor of pinch-hitters, making all these gaps even more extreme.

Hitting may be the most important part of the game, but it’s not the only part. Allen is in the game almost entirely because of his glove, which makes him a league-average player despite his batting line. But defense doesn’t factor in here. Using the same averages and the same assumptions, the nine hole hitter would have to play 232 more defensive innings than the leadoff hitter in order to qualify. In fact, the leadoff hitter would only have to play 981 defensive innings, which means they would qualify for the batting title, but not a Gold Glove.

I’m not saying any of this is necessarily a problem. Qualifying for the batting title isn’t a badge of honor in the same way that making 30 starts is for a pitcher. Besides, most players who find themselves on the bubble are, like Allen, in no danger of actually challenging for a batting title. But that doesn’t mean they shouldn’t get more plate appearances. Allen is running a 65 wRC+ while batting ninth, while the rest of the Braves hitters are at 48. All that pinch-hitting doesn’t seem to be paying off. Maybe it’s because teams are bringing in their best arms in those high-leverage situations, but maybe it means the Braves just need to let their second-worst hitter cook.

Davy Andrews is a Brooklyn-based musician and a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @davyandrewsdavy.bsky.social.

If the Braves trade Ozuna there will probably be fewer pinch hitter robberies moving forward. The Braves bench will be Eli White, Luke Williams, the third catcher, and whoever replaces Ozuna. At that point in really probably does make sense to just let Allen cook.