Shota Imanaga Has the Chance To Do the Funniest Thing Ever

I love a complicated contract. I love any excuse to use the word byzantine really, so once we’re into stair-step incentive clauses, cascading conditional extensions, and the finer points of Major League Baseball’s collective bargaining agreement, I’m having the most convoluted kind of fun imaginable. Today, I’m going to take you step by step through the complex world of Shota Imanaga’s current contract situation. As you likely know, the Cubs offered him a qualifying offer on Thursday. All we’re going to do here is break down as simply as we can how he got to that point and what it means. We’re not going to leave anything out. To be clear, Imanaga’s contract situation isn’t anywhere near the most complex one, but even so, it’s dizzying. We’re going to lose ourselves in the minutia. For fun.

I also love the logistics. I love following a chain of what happens when and why so precisely that you can’t help but be overwhelmed by the absurdity of the situation. And even before you dive in, free agent contracts are inherently absurd. They’re iron-clad agreements negotiated within the framework of an already-negotiated-to-within-an-inch-of-its-life CBA. They’re insured, and in recent years their conditionality has exploded to the point where they contain as many branches as a choose-your-own-adventure novel. But in the end, they just boil down to figuring out how much somebody’s going to get paid at their job. They just happen to be agreements about how much the most obscenely wealthy people in the entire world are going to pay people who are about to become generationally wealthy. Almost no one involved will ever have to worry about money for the rest of their lives. The people who really need the elaborate safeguards in the CBA and uniform player contracts are the ones who don’t make millions of dollars. But this is still a job; a high-pressure, high-stakes job negotiated between bitter rivals, and one side has a history of financial malfeasance that dates back to the 19th century. Of course, lawyers have to be involved. Everything needs to be spelled out, and my goodness is it spelled out.

The details in the CBA are there for very good reasons, but they’re mind-bogglingly specific. The title on the PDF calls it the basic agreement, and like any basic document, it’s 426 pages long. I just scrolled to a random page in the middle, and the topic at hand was who exactly gets photocopies of team financial documents so that the players can determine whether the owners are actually following the rules of the basic agreement. We’re 209 pages in, and we’re still talking about the logistics of the document itself.

One section stipulates what happens if a player gets called up for the National Guard. Another explains that all visiting clubhouses must contain a hydroculator. The last page is a full-page table that establishes an agreed-upon figure for how long it takes to fly from every city in the league to every other city in the league. Did you have a blast watching the swing-off that decided this year’s All-Star Game? Well, its format was codified in the CBA, which brings to the mind’s eye two teams of lawyers, red-eyed, ties loosed and collars mangled, monologuing 12 Angry Men-style in a conference room strewn with stale donuts and half-empty coffee cups about whether each player really needs unlimited pitches for their three swings when 10 pitches should really be enough to cover it.

Here’s a good-faith offer: I will personally bake a batch of cookies and mail them to the first FanGraphs reader who reaches out to me with some sort of honest-to-goodness proof that they’ve read the entire CBA. (Cookie variety of your choosing, but please be aware that my macaron game is rusty.)

So let’s get into this one contract. How hard could it be?

We’ll be relying on Cot’s Baseball Contracts for the details. When Imanaga came over from the Yokohama DeNa Baystars of NPB in January 2024, he signed a four-year deal with a limited no-trade clause. Sounds simple enough, but that’s just the convention for reporting contracts, based on how many years the player could get if they did everything in their power to stick around. Only the first two years were assured to happen, with two or three possible years added on by options that we’ll get to later. Also, Imanaga came through the posting system, which meant the Cubs paid his old club, Yokohama, a $9.825 million posting fee. Then he got a $1 million signing bonus. So let’s start there. The actual annual salaries were staggered. The Cubs agreed to pay $9 million for the 2024 season and $13 million for the 2025 season. That’s the straightforward part.

The escalator clauses come next. If Imanaga had won the Rookie of the Year in 2024, the Cubs would have added $250,000 to his 2025 contract. Cy Young Award escalators had the same structure, but they kept going. If Imanaga won a Cy Young at any point during the length of the contract, then his salary in all future seasons (including any option years) would increase by $1 million. If he finished second or third, it would increase by half a million. If he finished in the top 10, then it would increase by $250,000. The last one happened. Imanaga finished fifth in the 2024 NL Cy Young voting, adding a quarter million dollars to his 2025 contract and any possible future seasons.

These escalators have one more complicated aspect, because not all of the money would go to Imanaga. He would get 85% of all escalator money, but Yokohama would get the other 15%. So when he finished fifth in the Cy Young voting, he actually added $425,000 to his 2025 contract, while the other $75,000 went to the BayStars. Put all that together, and just in those first two years of the deal, there were seven different ways the contract could’ve gone. Imanaga could’ve gotten no bonuses, or he could’ve gotten any combination of the 2024 Rookie of the Year and Cy Young bonuses, all of which would’ve affected his pay for 2025 and beyond.

Next come the options. Maybe you’ve noticed that the reporting about Imanaga’s situation over the last couple days has come beneath oddly anodyne headlines. The one I saw most often was impressively passive: “Shota Imanaga Becomes Free Agent,” like there was a chrysalis involved or something.

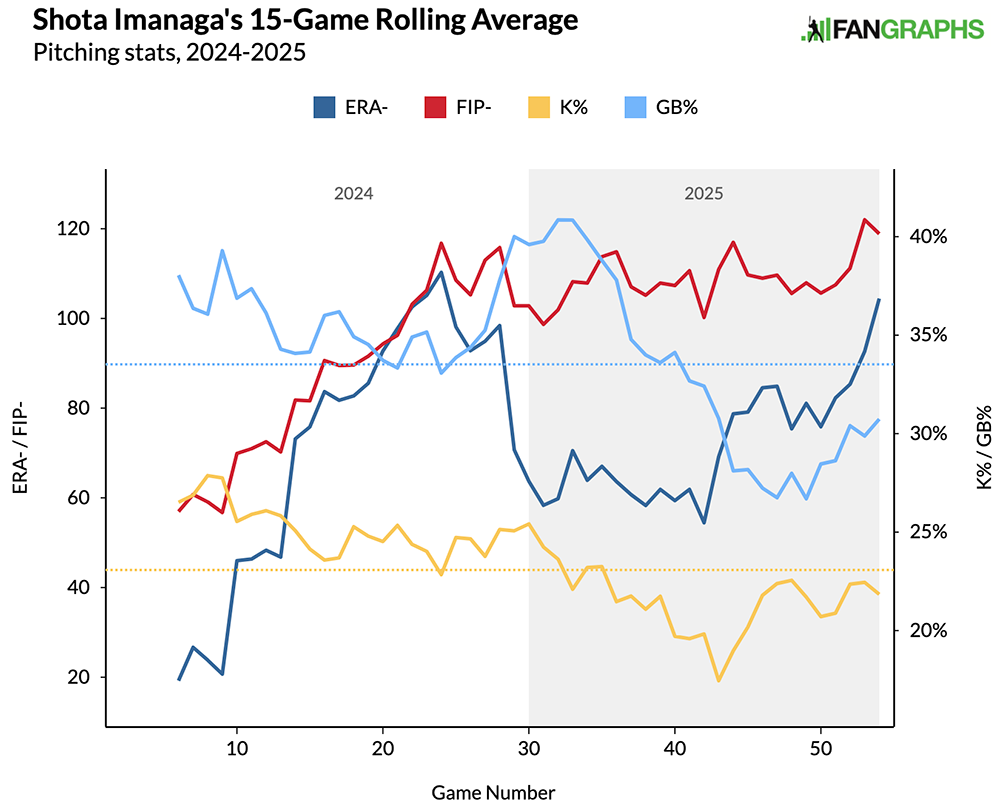

Why so bland? Because both the player and the team had a say. After the 2025 season, the Cubs had an option to bring Imanaga back for three years and $57 million. The structure of the team option was only a little bit complicated, in the sense that it was a bit front-loaded. Imanaga would have gotten $20 million in both 2026 and 2027, then $17 million in 2028. Going from $13 million in 2025 to $20 million in 2026 is an awfully big jump, and it would’ve been locked in because if the Cubs had exercised the option, Imanaga’s no-trade clause would have gone from limited to full. To take a quick detour into, you know, baseball, the graph below shows you why the Cubs may have been hesitant to sign up for three more years at a significantly higher price point. In keeping with the spirit of the exercise, I made it extra busy, so I’ll explain it a bit in the next paragraph.

The dark blue ERA- line makes it look like Imanaga is a steal at any price. The guy put up a 2.91 ERA last year, then 3.73 this year for a combined total of 3.28. That’s fantastic, despite some regression to the mean. But the other three lines are worrisome. His FIP has been rising ever since his hot start in 2024 because his strikeout rate has been dropping. His groundball rate plummeted this year. Although it’s not on this chart, he lost more than a tick of velocity on his fastball, dropping it to 90.8 mph. Even among the cohort of left-handed starters who threw at least 1,000 pitches, that put him in just the 19th percentile. Those are real reasons for concern, especially for a pitcher who would be in his age-34 season at the end of the deal.

Luckily for Imanaga, he had an insurance plan in his back pocket in the form of a player option for the 2026 season. Had he triggered it, he could’ve stayed in Chicago and made $15 million. If the graph I showed you was so ugly, why didn’t he take it and get that guaranteed pay raise? For starters, not all of that $15 million would have gone to him. Just like the escalator money, 15% of all option money over any part of the deal would’ve gone back to the BayStars. In other words, had he exercised this option, Imanaga actually would have gotten a pay cut from the $13.2125 million he made in 2025 (thanks to the fifth-place Cy Young finish) to $12.9625 million (which is 85% of $15 million and that $250,000 bonus).

Imanaga also had baseball reasons to think that he could go out and find a better, longer-term deal. Regardless of what FIP said, he was still able to keep the ball in the yard well enough to run a solid ERA in 2025. And there’s reason to expect his numbers to bounce back in 2026. Imanaga suffered a hamstring strain in May, and his strikeout rate, groundball rate, and velocity all rebounded a little bit at the end of the season. He might be back to his old self when he’s fully healthy, and he’s a crafty lefty with a long track record of success. It makes sense for him to bet on himself while he’s still in his early 30s.

By declining that option, Imanaga precluded a whole other branch of the contract. Had he exercised it and played for the Cubs in 2026, then they would have had an option for the 2027 and 2028 seasons, paying him $24 million in the first year and $18 million in the second year. (If those number strike you as odd, good eye. They look weird, but combined with that first player option, they add up to three years and $57 million, the same as the first option the Cubs declined.) And if they had declined that option, then he would have had one final player option, once again for $15 million, for the 2027 season. (As we established earlier, Imanaga would have only received 85% of all the figures I just mentioned, and those numbers are all contingent on Cy Young Awards, so at this point, we can add $250,000 to all of them in our heads.) When you combine the two player options, by leaving, Imanaga is turning down a guaranteed two years and $25.925 million in the belief that he can get a better deal in free agency. He’s probably right!

With that branch pruned before it had the chance to exist, Imanaga’s contract situation is finally clear, right? Of course not, because we’re back to the qualifying offer! As laid out in attachment 45 of the CBA on page 311, the qualifying offer is worth the average salary of the league’s 125 highest-paid players, which for the 2026 season comes out to $22.025 million. If Imanaga accepts, he’ll be getting a big pay raise, but he’ll also be forgoing the chance to test free agency for another year. It seems unlikely, but there’s always a chance that after a disappointing, injury-affected season, he could see it as a particularly gentle pillow contract. He gets that well-paid year to prove himself, but without the need to adjust to a whole new team and city.

I’m not 100% sure on my math here, mainly because holy God is this stuff convoluted, but I calculate that between all the option scenarios, the possibility of taking, rejecting, or not getting a QO at the end of each scenario, and four different award-escalator possibilities for each individual season, this contract could have played out 3,383 different ways. That includes everything from the most simple – Imanaga pitches two seasons, doesn’t get any awards votes, and leaves without a QO – to the most elaborate. That one involves Imanaga pitching six seasons for the Cubs. He wins the Rookie of the Year in 2024 and the Cy Young every year. The Cubs decline their three-year option, so he exercises 2026 player option, then the Cubs pick up their option for 2027 and 2028 and he accepts the QO in 2029. It earns him somewhere in the vicinity of $122 million over six years, rather than the two years and $23.2125 million he’s earned so far (not including his 2025 postseason share and 2024 All-Star stipend). What my heart really wants is for Imanaga to accept the QO, then pitch so well in 2026 that the Cubs are desperate to get him to sign an extension before the season is out, just to keep this organized chaos going for as long as possible.

I realize that this was probably a tough read on a Friday afternoon. Major league contracts are incredibly complicated for very good reasons, and although I would change about a million things about the current system if I were in charge of it, I don’t think the recent proliferation of options and incentive clauses is necessarily a bad thing. It’s logical for both sides to look for security blankets in case of injury or underperformance. It’s reasonable to have a system where you have your base pay and then bonuses if you perform really well, especially in a job like this one. But although it’s reasonable and logical, diving into the specifics of just one contract illustrates just how absurd the whole situation is, and that’s before we get into the formula for calculating how much meal money players get on road trips. Imanaga’s situation has played out in the most straightforward way possible, with none of the various option scenarios coming to fruition, but it’s still too complicated for a headline that sounds like it was written by a human being. So let’s keep it going.

Davy Andrews is a Brooklyn-based musician and a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @davyandrewsdavy.bsky.social.

GREAT breakdown. I was following his contract “dance” these last two weeks.

I have a feeling come May 2026 Shota will be wishing he took the Cub’s qualifying offer.

Did I miss something about how he had rejected it? He has at least a week to make a decision.

I think OP is assuming since most QO do get rejected.