Tanner Scott and the Ideal Zone Rate

Let’s start with a thought experiment, then we’ll get to the guy in the picture up there. Say you’ve got an unhittable fastball. Every time an opposing batter swings at it, they miss. With such a pitch, you’d want to hit the strike zone every time. Only good things can happen in the strike zone. Either the batter takes and you earn a called strike, or they swing and you earn a swinging strike. Outside the zone, you’d run the risk of throwing a ball because the batter lays off it.

Now, say you’ve got an extremely hittable fastball. Not only does it never generate a whiff, but every time the batter swings at it, they also hit a home run. You’d never want to throw that pitch in the zone. You wouldn’t want to throw it much at all. Maybe you’d use it as a waste pitch to change the batter’s eye level, just every once in a while, and so far outside the zone that they wouldn’t even think about swinging at it. But that’s it.

Those are extreme examples, but my point is to introduce the concept of an ideal zone rate. Every pitcher (and every pitch) in baseball lives somewhere between those two extremes. Some pitchers should live in the zone and some should avoid it. All sorts of factors inform that ideal zone rate: how likely the pitch is to earn a whiff, how likely it is to earn a chase, how hard it tends to gets hit, whether it tends to gets hit in the air or on the ground, how it interacts with the rest of your repertoire, how it performs in different locations, how well you’re able to locate it, how confident you feel in it, the count, batter, situation, and so on, and so on.

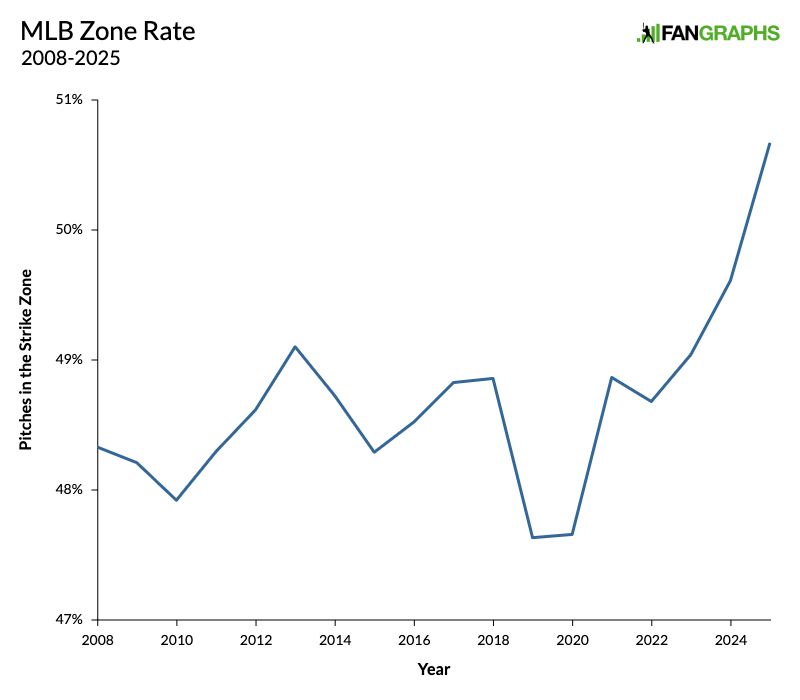

Lately, the calculus has shifted somewhat. The zone rate has been rising because pitchers have been instructed to aim down the middle and trust in their stuff. In 2024, 49.6% of all pitches were in the strike zone and 26.5% were specifically in the heart zone (the area at least one baseball’s width from the edge of the zone). Both of those numbers were the highest rates we’d seen since the start of the pitch tracking era in 2008, and both of those numbers were surpassed in 2025, when for the first time ever, more pitches hit the strike zone than missed it. Across baseball, the ideal zone rate has increased.

That brings us to Tanner Scott. Coming into the 2025 season, Scott looked pretty much unhittable. From 2023 to 2024, he put up a combined 2.04 ERA and a 2.53 FIP. He even had six scoreless postseason appearances, too. He ran a strikeout rate over 31%, a groundball rate over 50%, and a hard-hit rate under 27%. He earned tons of whiffs and tons of chases. Scott’s game had just one flaw: He walked too many people. He greatly cut down on the walks in 2023, but they bounced back in 2024. Coming into last year, he had a career walk rate of 12.6%. Among pitchers with at least 300 innings pitched, that was the 17th-highest career walk rate of this century.

So, ahead of the 2025 season, Scott signed with the Dodgers for a bajillion dollars and cut out the walks. In 2023 and 2024, he posted a combined 51.9% zone rate. In the first half of 2025, he was at 56.7%. That’s an enormous jump, as Michael Baumann noted in an article titled, “Tanner Scott, or an Impostor Who’s Stolen His Identity, Is Throwing a Ton of Strikes.” Scott didn’t walk his first batter until May 5. That was by design. “We’re asking him to fill it up a little more,” assistant pitching coach Connor McGuinness told The Athletic a few days later. “He’s not expanding the zone, which would lead to more miss, typically, and trying to get those weaker outs as it goes through.” By May 16, Scott had a 1.74 ERA and 2.51 FIP. It was a success story, but you know as well as I do what happened next.

Even through mid-May, amid all that success, things looked a little different under the hood. Scott’s groundball rate and strikeout rate had fallen. His hard-hit rate had risen by a huge margin. Those numbers caught up to him in a big way. From May 17 on, Scott ran a 6.27 ERA and 5.76 FIP. Toward the end of June, he even tried going back to his old, zone-avoidant ways. From the first half to the second, his zone rate fell from 56.4% to 47.1%. It didn’t help. The strikeout rate never ticked back up even though the walk rate did. He also started giving up tons of homers. Things got ugly.

Below are heat maps of Scott’s pitches in 2024 and 2025, courtesy of Baseball Savant. Even though Scott went back to missing the zone again during the second half, the difference in his approach is plain to see.

Scott throws a four-seamer and a slider. The four-seamer rises and has about six inches of arm-side run. The slider stays on plane and has about six inches of glove-side break. It’s a classic combination, and in 2024, Scott’s gameplan was simple: Keep the ball down and to the glove side. He threw both pitches right on the corner, low-and-in to righties and low-and-away to lefties. If they swung, they whiffed or drove the ball into the ground. If they didn’t swing, they’d have a chance of drawing a walk. Because it takes four walks to score a run, the plan worked pretty well. Scott wasn’t afraid to elevate the fastball for a whiff at the top of the zone, but just as often, he went for that low corner. His ideal zone rate was low.

That changed in 2025, at least for a while. Scott started throwing both pitches higher. He elevated the fastball more and stopped going for the corner. The average slider location moved toward the corner, but all of sudden it was much more likely to be inside the zone than below it. Both pitches were in more hittable locations.

At least in theory, one benefit of the 2025 approach was that the pitches would tunnel better. In 2024, both the fastball and slider tended to end up at same spot. That meant the four-seamer, with its induced break, had to start out lower than the slider, and that difference in release angle might have made them it easier for batters to tell them apart. In 2025, though, the two pitches seemed to have the same release angle. When aimed at the same corner, the slider would still break more toward it, while the fastball would rise and catch more of the plate. Yes, tunneling the two pitches made them more difficult to decipher coming out of the hand, but it also gave batters reason to hope. They knew they might actually see a fastball they could hit, so they hunted it. As a result, the fastball’s swing rate went way up, both inside and outside the zone. Despite all the extra pitches in the zone, his called strike rate actually fell.

As tidy a narrative as this is, it’s not fair to say this change in approach is the entire reason that Scott struggled so mightily. His fastball velocity dropped by half a mile per hour from 2024, largely because his velocity always seems to tick up later in the season, and he missed a month due to elbow inflammation just after the All-Star break. Some mechanical change also caused his pitch movement to shift a bit more than an inch toward his arm side on both pitches, which likely made his fastball movement more predictable to hitters. He also raised the possibility that batters knew what was coming, telling The Sporting News, “I don’t know if I’m tipping or what, but they’re on everything. It sucks.”

We also have to allow for the effect of randomness here. Scott’s a reliever with the attendant small, noisy sample, especially on balls in play. While his fly ball rate and launch angle really did skyrocket, so too did his rate of home runs per fly ball, and that’s usually an indicator of luck. His wOBA was a bit higher than his xwOBA, and Statcast thinks that rather than 11 home runs, he deserved to give up 8.2.

So we can’t just blame Scott’s location. In fact, both Stuff+ and PitchingBot liked his command better in 2025 than in 2024. However, it’s hard not to draw the line between elevating your fastball more often and suddenly allowing nine home runs on fastballs, the same amount you’d allowed over the previous six seasons combined. It’s also hard not to see batters going after your fastball way more aggressively and connect it to the fact that you’re leaving it in a hittable location more often, even if that location grades out better according to the pitch models because it results in fewer balls. Moreover, based on the fact that Scott went back to his old approach after he started struggling, it certainly seems like he and the Dodgers blamed the location on his troubles. Scott has three more seasons with the Dodgers on his contract, and it’s fair to assume they’ll come up with other ways to try to help him improve in the future. Filling up the zone seems to be on hold for now.

Davy Andrews is a Brooklyn-based musician and a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @davyandrewsdavy.bsky.social.

He and Kirby Yates both seemed to get to 2 strikes before leaving that pitch middle middle. At least that’s what it seemed like to a fan that watched a lot of them in 2025. Any idea how many of his homers happened with 2 strikes?

That Tanner Scott was probably healthy and didn’t pitch a single pitch in the post season says a lot about a lot.

So four of Scott’s 11 home runs came with two strikes, but none of them was classified by Statcast as being in Zone 5, the middle of the plate. He also had a medical procedure on a sensitive area in October, which seemed to explain at least some of his absence during the playoffs.