The Mariners Didn’t Challenge That Play at the Plate, So We Challenged It for Them

It was really close. On Sunday, in Game 1 of the American League Championship Series, in the top of the first inning, with one out and runners on first and third, once and future hero playoff hero Jorge Polanco hit a bouncer to the third baseman. The runner on third was going on contact, but the runner on third was Cal Raleigh, and while relatively quick for a catcher, the Sultan of Squat is not exactly known for his speed. Had the ball been hit anywhere other than directly at a corner infielder, he might have beaten it easily. Instead, Addison Barger’s throw beat Raleigh to the bag by at least three metres (the game was in Canada, after all). But it was still really close.

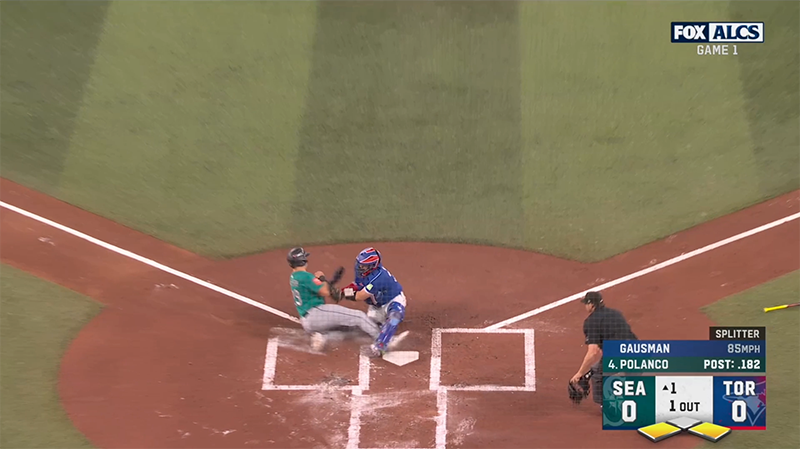

The throw arrived in plenty of time, and it was by no means off target. To make sure he ran no risk of hitting the runner, Barger wisely threw the ball toward the right side – the first base side – of catcher Alejandro Kirk’s body. The throw wasn’t high either, but it did arrive at shoulder height. Raleigh was running as hard as he could, and in the time it took Kirk to swing his catcher’s mitt from high on his right side to low on his left side, he’d closed the distance to roughly one metre. Then Kirk made an important decision. With Raleigh bearing down on him, he chose not to keep swinging the glove down and toward the plate. He reached out for a high tag and swept the left side of his body out of the way in the same moment. Self-preservation undoubtedly played a role in the decision. It cost him valuable centimetres (God, this feels wrong), and it very nearly allowed Raleigh to sneak his right cleat between Kirk’s legs and onto home plate before his torso crashed into the mitt. For the briefest of moments, the two catchers looked like colliding galaxies, smashing then spinning together as their gravitational fields intertwined:

In real time, the play went from looking like a sure out to an impossibly close call. Maybe Raleigh got his foot in there and maybe he didn’t. The call on the field was out, and unbelievably, the Mariners declined to challenge it. The video never got dissected by the replay room in New York. The chief marketing officer of Zoom Communications, Inc. surely wept.

In theory, teams should hold on to their challenges unless they feel confident that the call in question will be overturned, but in practice, they have two challenges in the postseason, and the ability to request an umpire’s challenge means that there’s effectively no penalty for wasting a challenge. This one wouldn’t have been a waste. The play looked just about as close as it could get, and it offered the chance to take an early lead in Game 1 of the ALCS. It was a no-brainer.

After the play, the broadcast showed seven replays over a period of 55 seconds. Two of those replays were repeats, so in all, we got six angles of the play at the plate. Americans and Canadians leaned in toward their televisions and watched intently for those 55 seconds, but even with some of the replays coming in slow motion, it just wasn’t enough time to tell for certain. Had Kirk’s tag caught Raleigh’s arm or traveled the extra distance to his stomach? Had Raleigh’s cleat, obscured in a cloud of dirt and chalk, caught the front of the plate or popped over it? Which happened first? The video below shows exactly what the viewer at home saw. It would be impossible for anyone to say what happened with certainty after just one viewing of these clips:

First, obviously, we got the real-time action, starting with the center field camera and cutting to the high home camera once Polanco put the ball in play. Even if the play had been slowed down, the distance and the angle likely made it impossible to tell when Raleigh touched home and when Kirk touched Raleigh:

Next, we got a view from directly behind home plate, once again at full speed. Raleigh’s body blocked the view of Kirk’s glove, making it impossible to tell when the tag happened:

The play happened much too fast to tell what happened at game speed, so the next shot came in slow motion. It was shot at a low angle from down the left field line, which meant the camera was behind Raleigh’s body, which was once again blocking both his foot and Kirk’s glove:

The next slow motion replay came from a bird’s eye view from above home plate. It was a great shot, but Kirk’s left foot blocked the corner of the plate, making it impossible to tell when Raleigh’s foot touched home. The high angle also made it tough to tell whether Kirk’s glove caught the bottom of Raleigh’s right arm or passed right underneath it and touched him in the stomach, a distinction that looked certain to be the difference between out and safe:

Next came a beautifully oversaturated shot from the first base dugout, likely using the super slow-motion cameras that capture shots of check swings. Unfortunately, the angle meant that this time, Kirk was the one between the camera and the mitt, blocking the view of the tag. The low angle also foreshortened home plate so much that it almost disappeared. It’s hard to know when the foot touches an invisible plate:

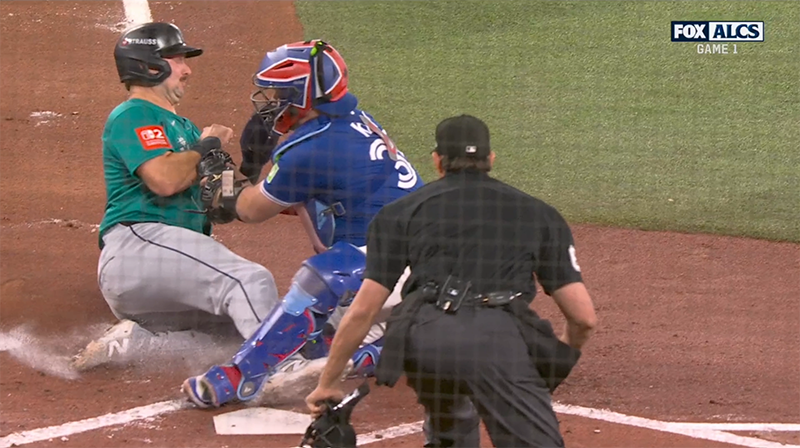

The final shot showed the home plate umpire’s angle of the play (so much so that the umpire very nearly blocked the camera’s view entirely). As we’ll see in a moment, this proved to be the decisive angle, but even in slow motion, it was too much for the human eye to track both the progress of the foot and the moment the glove actually touched the runner. Note the expression on Raleigh’s face. He looks like a three-year-old who finds tags every bit as disgusting as broccoli:

After the first pitch to the next batter, the broadcast cut to shots of an impassive John Schneider in the Blue Jays’ dugout and a relieved-looking Barger at third base, then repeated the replays from the overhead view and the umpire’s view. And then the game went on. At that point, no one at home could know for certain whether the call had been correct, or whether the Mariners’ risky decision to let the play go unchallenged would prove to be catastrophically cautious:

This is the decisive angle, and it’s slowed down even further from the replay on the broadcast. Even at this slow speed, and even zoomed in on the foot or the glove, the difficulty of the call is apparent. There likely wouldn’t have been a clear enough shot for the replay officials to do anything but let the call stand. Raleigh’s cleat sent a wave of dirt and chalk from the batter’s box ahead of it. You need to watch several times before you start to get a sense of where the chalk ends and where the cleat begins:

The view of the tag is clearer, but not by all that much. It’s clear that Kirk did tag Raleigh’s wrist rather than his stomach, saving him precious centimetres. But because the view is from behind, the only way to tell when the tag actually took place is to look and see when pressure from the wrist starts to deform the tip of the glove. The first sign is that the back half of the glove, the finger side, starts to pop up above the front half, the thumb side. But even from this view and at this speed, it’s still not as obvious as we’d like:

The cloud of dust arrives at the corner of home plate at the exact same moment the glove starts to deform. In fact, there’s a puff of white dust just ahead of Raleigh’s heel that really fools you into thinking it’s part of the shoe, and that puff of dust was safe! But Raleigh’s heel doesn’t tough the exact corner of the plate. It’s a few centimetres over to the right, crossing the front of the plate just a frame or two after Kirk’s glove starts to deform, and a frame or two after the puff of dust. Raleigh is out by just about as small a margin as you can imagine. (Fine, I’ll say it: Raleigh was out by millimetres.) Below is side-by-side footage, with the moment that each action takes place marked with a big “NOW.”

Reasonable people might disagree even after seeing this footage, but this is as good as we can get without being inside the replay room ourselves. Now that we’ve settled it as well as we’re going to settle it, let’s all head out to Tim Hortons.

Davy Andrews is a Brooklyn-based musician and a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @davyandrewsdavy.bsky.social.

Well great job even though inconclusive

Not inconclusive at all. He was out.