The WPBL Has Teams and Players Now

The Women’s Pro Baseball League held its inaugural draft on Thursday night. For many of the players who heard their names called, getting to play professional baseball is a dream they’ve carried since childhood, one they knew might never come true. Play won’t get underway until next August, but with the WPBL draft now in the history books, the dreams of 120 women are meaningfully closer to being realized.

Thursday night’s draft was the culmination of a busy few months for the new league. Since I last wrote about the WPBL in January, the league has announced key logistical information, such as the number of teams that will play during its first season, where those teams will play, and how much the teams will pay the players, and has also provided an update on the WPBL’s media and broadcast strategy. But despite all the new intel on how the league will be run, a few key components are still unknown. So before recapping the draft and the open tryout that determined the pool of draft-eligible players, let’s get up to date on what we do and don’t know about the WPBL so far.

If this is the first you’re hearing of the WPBL, here’s a quick primer. It’s a professional baseball league for women, the first of its kind since the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League (AAGPBL), which ran from 1943 to 1954. The WPBL was co-founded in October of 2024 by Justine Siegal — who is best known for founding Baseball For All, “[A] girls baseball nonprofit that builds gender equity by creating opportunities for girls to play, coach, and lead in the sport” — and Keith Stein, a businessman, lawyer, and member of the ownership group for a semiprofessional men’s baseball team in Toronto.

When the league was first announced, the plan was to field six teams, all based in the Northeast (presumably to minimize travel expenses in the early going), with the intent to expand nationwide as the league grew. But when the WPBL officially announced the teams for its debut season, the number had dropped from six to four, with cities situated on both coasts. New York, Boston, Los Angeles, and San Francisco will host the league’s first four teams, but not until 2027. During the 2026 season, the league will play all of its games at Robin Roberts Stadium in Springfield, Illinois, about three hours southwest of Chicago. Stein told Front Office Sports that though the initial teams will be situated on either coast, they want to appeal to fans across the country, “Our sport is for everybody,” Stein said. “It’s for middle America, everybody. We thought our teams are on these two coasts, it would be good to be in the middle of the country.”

The stadium, which seats 5,200, is operated by Golden Rule Entertainment (GRE) and will not be shared with any other leagues during the WPBL’s six-week regular season plus its playoffs. GRE also owns multiple teams in the Prospect League, a wood-bat collegiate summer league. The company is currently seeking a naming rights sponsor for the stadium to fund needed renovations for the facilitiy. Issues with the field’s storm drainage, along with “other problems,” forced the Springfield Lucky Horseshoes (one of GRE’s Prospect League teams) to cancel several home games last season, as well as the league’s All-Star game.

While a majority of the WPBL’s games will be played in Springfield, the league plans to play several barnstorming games in other cities, including the future homes of its first four teams, though those plans have yet to be finalized. Any other cities selected to host barnstorming games will likely be on the league’s short list for expansion, as Stein told Front Office Sports that the league plans to add two additional teams in 2027.

For those unable to see the WPBL play in-person, it’s unclear where exactly its games will air and whether or not fans will need a paid subscription to watch from home, but the league has announced a partnership with Fremantle, a media production company with a résumé spanning reality TV, game shows, film, and documentaries. According to The Athletic, the WPBL’s deal with Fremantle includes, “[E]verything from producing and distributing game broadcasts to creating original content, securing sponsors, marketing the league globally and helping the league sign a national broadcast partnership. The company will also develop shoulder programming (such as pre- and post-game shows, for example) and documentaries.”

Securing a big-name media company suggests that the league hopes to establish a high standard for its programming, which should, in turn, help attract potential fans. Unfortunately, the draft broadcast, which aired on the league’s YouTube channel and social media feeds, failed to capture the excitement that comes with getting drafted into a pro league. (It’s unclear whether Fremantle was involved with the production.) For a league in its first season, offering opportunities that these players have never had before, it should have been easy to produce a broadcast that conveyed the stakes of the moment. This was one of the league’s first real chances to connect with fans and get them invested in the league the same way the women drafted are clearly invested in playing baseball and moving the women’s game forward. Instead, they took an event that lends itself to a natural barrage of emotional peaks and rolled out something completely flat, and a key storytelling opportunity was missed.

The draft order was determined by the WPBL’s law firm, with the first pick going to San Francisco, followed by Los Angeles, New York and finally Boston. Each of the four teams made 30 picks using a serpentine format (serpentine is my preferred term; they called it a snake draft) for a total of 120 picks. Not coincidentally, the pool of draft-eligible players also totaled 120, so any player who made the pool knew they would be drafted, which immediately lops off a decent chunk of the suspense typically associated with a draft. However, half of the players drafted won’t make their team’s final roster. Though each team made 30 picks, their rosters only accommodate 15 players, which injects some tension back into the equation, since the deeper a player fell in the draft, the lower their odds of making the team.

As for where the 120-player pool came from, that was determined back in August. The league hosted a four-day open tryout in Washington D.C., where a contingent of 600 players from 10 different countries was gradually whittled down to 100. Unlike the draft process for MLB, which typically only includes players from Canada, the U.S. and Puerto Rico, the WPBL cast an international net when putting together its draft pool; the final group of eligible players comprised representatives from a dozen countries around the world. A few players who couldn’t make the tryout in-person were admitted based on video submissions and a few others were scouted and recruited by the league, bringing the total to 120. The full list of draft-eligible prospects was revealed in late September.

So the big reveal on draft day was less the who and more the where and when. The broadcast opened with a video montage of footage from the tryouts to warm up the audience for an evening that should have been full of positive energy. But rather than riding that momentum straight into the draft, they cut to MLB Commissioner Rob Manfred, who monotoned behind dead eyes for almost a full minute about how baseball is for everyone, a fact exemplified by MLB both on the field and in its front offices. As an aside, have you ever caused yourself physical pain because you accidentally rolled your eyes too hard? I bet Kim Ng has.

Next, viewers were welcomed in by CJ Silas, ESPN radio host and stadium PA announcer, who hosted the draft and announced all 120 picks. That process of announcing the picks took less than 55 minutes, and as you may have guessed based on that pace, teams were not submitting picks in real time, as is typical for most drafts. Instead, the entire exercise was completed beforehand, making the broadcast more of an announcement of draft results than a live-action draft. Without the deliberation time between picks, viewers learned very little about the personal or baseball backgrounds of the players selected. We were further deprived of their in-the-moment reactions to hearing their names called; as a substitute, we got rehearsed statements with the players speaking directly into their phone’s selfie camera, filmed long after that initial reaction had worn off.

Around the halfway mark, the pace really picked up. No more videos were shown, with photos and basic biographical information flashing on the screen as Silas powered through the selections at a cadence befitting an auctioneer. On the one hand, I appreciated the efficiency; on the other hand, delivering the picks with such breakneck speed left me wondering if this meeting, er, draft could have been an email. Which isn’t the energy you want from a draft! This isn’t like the MLB draft, where players are selected and then disappear into their team’s minor league system for two to five years (or two months, if the team in question is the Angels). These players will be taking the field next summer. The time to start hyping them up is now. Yet as I wrote this, mere hours after the conclusion of the draft, the only detail from a player’s bio I could remember learning from the broadcast is that Alli Schroder, the fifth overall pick by Boston, also fights wildfires. I also jotted down that Nadia Diaz has some cool looking tattoos. But that’s it. That was all I got.

But for all my griping about the draft’s presentation, I will concede that certain structural factors did create narrative challenges for the league. Notably absent from the league’s various press releases over the last several months has been any announcement of team ownership groups. Initially, the WPBL planned to go the more traditional route, with individual owners for each team. But they’ve since pivoted to a single-entity model, where the league retains ownership of all the teams, as a means of prioritizing parity.

Under this model, the draft dynamic is no longer one of individual teams strategizing against one another to acquire the most talent; it’s a league strategizing to construct four evenly matched teams. Without distinct front offices, the details on who exactly was making the picks for each club is a bit murky; the league’s PR director told Jen Ramos-Eisen, “There were 12 coaches involved in the process of selecting players to the teams including those who were at the tryouts. This process was led by Alex Hugo with the WPBL,” and added that coaching staffs would be announced in 2026.

Unrivaled, the 3×3 women’s basketball league, also operates under the single-entity model and they use a similar approach for selecting teams. Rather than conducting a traditional draft, Unrivaled’s coaches work together to construct the league’s eight rosters. The catch is that they don’t know which roster they’ll be assigned to coach until after the teams are finalized. Then, in lieu of a draft, Unrivaled live-streams a roster reveal show. It’s also worth noting that Unrivaled has mastered the art of unveiling which players will be participating in the league using a social media guessing game that doubles as a means of giving fans an opportunity to get to know the players better.

Unrivaled proves there are still ways to build intrigue around roster construction and generate hype for the players. Which isn’t to say that Unrivaled’s tactics would translate perfectly to the WPBL. They wouldn’t. But with some creativity, the WPBL could have found a more compelling way to introduce its teams and players to the world, as opposed to pretending they were conducting a traditional draft and rattling off a list of names in rapid succession.

On the topic of parity, we should discuss the last major piece of information announced by the league in recent weeks: player payroll. During its first season, each WPBL team will operate under a $95,000 salary cap, which is an average of around $6,000 per player, given the 15-player rosters. Over a six-week regular season, that’s $1,000 per week. The league also intends to cover living expenses during the season and give players a cut of any sponsorship income, though the exact percentage hasn’t been disclosed. If we evaluate the total compensation package as a starting point for a new league, it isn’t terrible. It’s nothing the league should be bragging about, but it could certainly be worse. Just ask anyone who played minor league baseball prior to 2022. For now, I’m willing to reserve judgement until we see how the payscale evolves for 2027.

But enough agonizing over the league’s innerworkings, let’s get a feel for the composition of the newly drafted player pool. As the names and demographic information flew across the screen during the draft, it was striking how many players hailed from outside the U.S. The table below has the full breakdown by country, with MLB’s corresponding 2025 numbers shown as a point of reference:

| WPBL | MLB | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Number | % | Number | % |

| USA | 61 | 50.8% | 1081 | 73.5% |

| Canada | 20 | 16.7% | 22 | 1.5% |

| Japan | 10 | 8.3% | 13 | 0.9% |

| Mexico | 9 | 7.5% | 15 | 1.0% |

| Australia | 9 | 7.5% | 2 | 0.1% |

| South Korea | 4 | 3.3% | 5 | 0.3% |

| Puerto Rico* | 2 | 1.7% | 27 | 1.8% |

| Venezuela | 1 | 0.8% | 93 | 6.3% |

| France | 1 | 0.8% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Curaçao | 1 | 0.8% | 4 | 0.3% |

| United Kingdom | 1 | 0.8% | 1 | 0.1% |

| Dominican Republic | 1 | 0.8% | 144 | 9.8% |

| Cuba | 0 | 0.0% | 34 | 2.3% |

| Colombia | 0 | 0.0% | 8 | 0.5% |

| Panama | 0 | 0.0% | 6 | 0.4% |

| Nicaragua | 0 | 0.0% | 3 | 0.2% |

| Aruba | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 0.1% |

| Germany | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 0.1% |

| Italy | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 0.1% |

| Taiwan | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 0.1% |

| Bahamas | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 0.1% |

| Honduras | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 0.1% |

| Peru | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 0.1% |

| Portugal | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 0.1% |

| South Africa | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 0.1% |

Just over 50% of WPBL draftees are from the U.S., compared to over 73% of MLB players. And despite a player pool less than one-tenth the size of MLB, the WPBL comes close to matching MLB’s total number of players from Canada, Japan, and South Korea, and exceeds its number of representatives from Australia, though MLB has far better representation when it comes to the Dominican Republic, Venezuela, and Puerto Rico. The differences in national representation are likely explained in part by certain social cultural differences. Certain countries may place more or less importance on women’s sports relative to the U.S., while others may be more likely to encourage girls to keep playing baseball as they get older, rather than incentivizing a switch to softball, as frequently happens stateside.

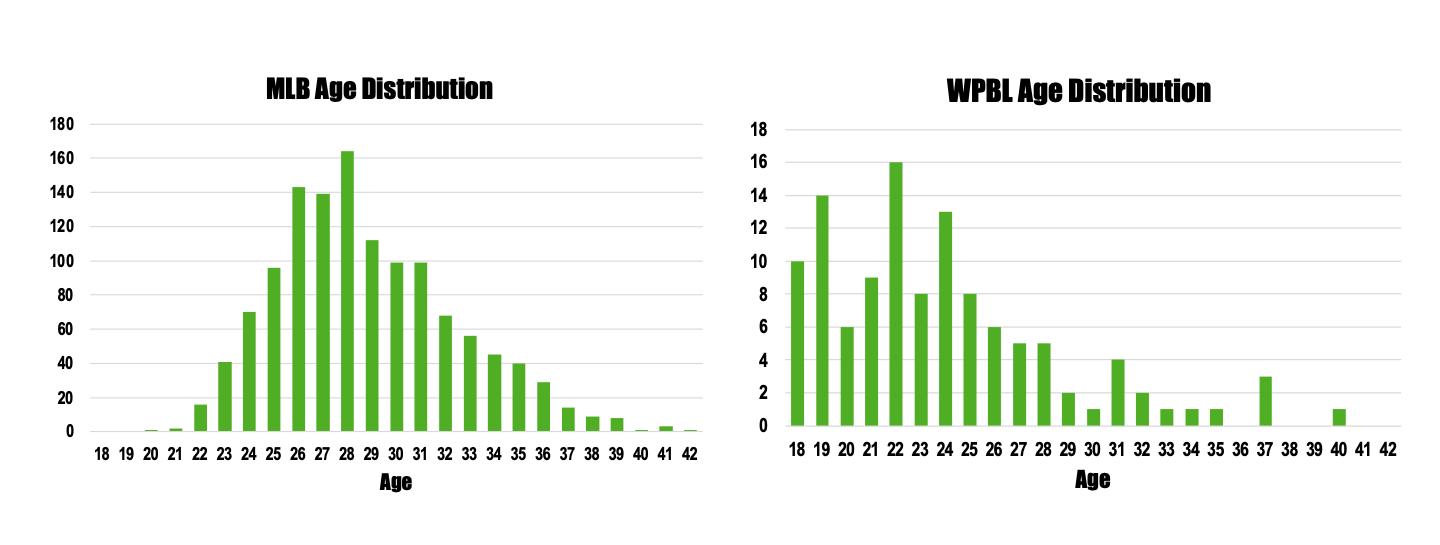

Meanwhile, after Los Angeles used its fourth pick to select 37-year-old Meggie Meidlinger, a right-handed pitcher from Marietta, Georgia, I was curious about the WPBL’s age distribution, particularly compared to that of an established league like MLB. The WPBL actually skews much younger, which can mostly be explained by the lack of professional opportunities for women prior to the founding of the league. Beyond playing for national teams, 37-year-olds like Meidlinger had no reason to stay in playing shape later into adulthood. As the WPBL persists, I’d expect the average player age to tick up year-over-year until the distribution starts to look more like MLB’s normal distribution:

As for individual players, here’s a brief look at each team’s first selection.

San Francisco: Kelsie Whitmore, RHP

A 27-year-old from San Diego, Whitmore has made headlines several times over the years for historic “firsts.” In 2016, Whitmore and Stacy Piagno were the first women to play professional baseball since the 1950s, when women played in both the Negro Leagues and the AAGPBL. In 2022, Whitmore was the first woman to play in the Atlantic League, suiting up for the Staten Island FerryHawks. And in 2024, she became the first woman to play in the Pioneer League as a member of the Oakland Ballers. Currently, Whitmore plays for the Savannah Bananas. After she was selected with the first overall pick, Whitmore noted that after starting her professional career in the Bay Area with the Sonoma Stompers, she was excited to be heading back to the Bay to play for San Francisco.

Los Angeles: Ayami Sato, RHP

At 35, Sato is already a legend in the women’s baseball world. Pitching for Japan’s National Team, Sato was named MVP of the Women’s Baseball World Cup in three consecutive tournaments and is the only player to win the award multiple times. In the Japan Women’s Baseball League, Sato holds the records for career complete games, strikeouts, and complete games in a season. In 2024, she signed with the Toronto Maple Leafs (no, not those Maple Leafs) and became the first woman to play in the semi-professional Intercounty Baseball League based in Ontario, Canada.

New York: Kylee Lahners, 3B

The first position player drafted, the 32-year-old Lahners played collegiate softball at the University of Washington, where she earned All-Pac-12 honors all four years. At age 25, she made the jump to baseball and joined Team USA, where she’s been a key contributor ever since. During the 2019 COPABE Women’s Pan-American Championships she batted .625 over seven games, logging a seven-RBI game against the Dominican Republic and earning a tournament award for most runs produced after racking up 17 RBIs and scoring 15 runs.

Boston: Hyeonah Kim, C

Kim, age 25, joins the WPBL from South Korea, where she plays for the Korean National team. She recently competed in the 2025 BFA Women’s Baseball Asian Cup, where over seven games she slashed .409/.483/.500, scored nine runs, notched 15 RBIs, went 8-8 in stolen base attempts, and struck out just once. Speedy catchers who hit for contact are anomalous in men’s baseball, but in a women’s league, a profile like Kim’s might not be quite so rare.

And in the category of Other Players Drafted Who You’ve Definitely Heard Of, Mo’ne Davis was selected 10th overall by Los Angeles. In 2014, Davis pitched a shutout in the Little League World Series at age 13, earning herself a spot on the cover of Sports Illustrated. She continued to play baseball through high school, and then, like so many girls who grow up playing baseball in the U.S., she eventually switched to softball. Davis played two years of softball at Hampton University, an HBCU in Virginia, but the switch from baseball didn’t take. Softball simply wasn’t her sport. Without any viable opportunities to return to baseball, Davis defiantly declared her playing days to be over. Until she came upon a social media post about the WPBL, that is. After six years away, the new league allowed the 24-year-old to imagine a world where her playing days didn’t have to be over.

The WPBL drafted a strong cohort of women in its inaugural draft, and if the league can hold up its end of the bargain, maybe Davis will be among the last wave of young girls forced to preemptively declare their playing days are over because they can’t see any viable opportunities.

Kiri lives in the PNW while contributing part-time to FanGraphs and working full-time as a data scientist. She spent 5 years working as an analyst for multiple MLB organizations. You can find her on Bluesky @kirio.bsky.social.

I’m rooting for this league!

Same, but I worry that it lacks the same level of backing as the WNBA unless I’m missing something. It took decades of support before the WNBA started to really break out over the last few years. Without that this league could be a flash in a pan. Especially with the first season primarily being played in a single city. I just don’t see how they make the numbers work.