Amed Rosario Can’t Stop Running

I don’t know if you’ve heard, but here at FanGraphs we enjoy the occasional number. Even our logo has its own bar graph. Today our topic is competitive runs, a statistic that rarely gets the love and appreciation it deserves, due to the fact that it’s mostly made up. Competitive runs is a classification created for Statcast. In order to measure average sprint speed, you need a pool of plays when players will presumably be running their hardest:

Competitive runs are essentially just the sample size. When you go to Baseball Savant’s leaderboard, the players are always sorted from fastest to slowest. However, you can also sort by competitive runs, and I can never resist. All season long, one player was absolutely trouncing the field:

| Player | Competitive Runs | Sprint Speed |

|---|---|---|

| Amed Rosario | 342 | 29.5 |

| Brandon Nimmo | 282 | 28.7 |

| Vladimir Guerrero Jr. | 279 | 26.6 |

| Trea Turner | 276 | 30.3 |

| Steven Kwan | 272 | 28.4 |

Amed Rosario is the grand champion of competitive runs. The difference between Rosario in first place and Brandon Nimmo in second place is the same as the difference between Nimmo and Jeff McNeil in 34th place. I’m sure Nimmo takes some solace in knowing that he’s the undisputed leader of the non-competitive run. Whether it’s a walk or a hit by pitch, the dude straight up loves scampering to first base for his own particular reasons:

Turning our attention back to Rosario: It’s not as if he’s just racking up competitive runs as a counting stat. He also leads the league on a rate basis, no matter which rate you choose:

| Rank | Player | Per Plate Appearance | Rank | Player | Per Ball in Play | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Amed Rosario | 51.0% | 1 | Amed Rosario | 64.5% | |

| 2 | Isiah Kiner-Falefa | 48.2% | 2 | Isiah Kiner-Falefa | 60.9% | |

| 3 | Starling Marte | 44.2% | 3 | Starling Marte | 60.4% | |

| 4 | Luis Rengifo | 43.4% | 4 | Brandon Nimmo | 60.0% | |

| 5 | Steven Kwan | 42.8% | 5 | Juan Soto | 59.6% |

I don’t know about you, but I think this is incredibly fun. Competitive runs is an incidental statistic. It’s just scaffolding for another stat, but there’s one person who plays baseball like competitive runs is his own personal pinball machine. The other reason I love it is that even though competitive runs exists only to serve a higher master, it’s still a descriptive stat in its own right. A player’s competitive runs total tells you plenty about the way they play the game.

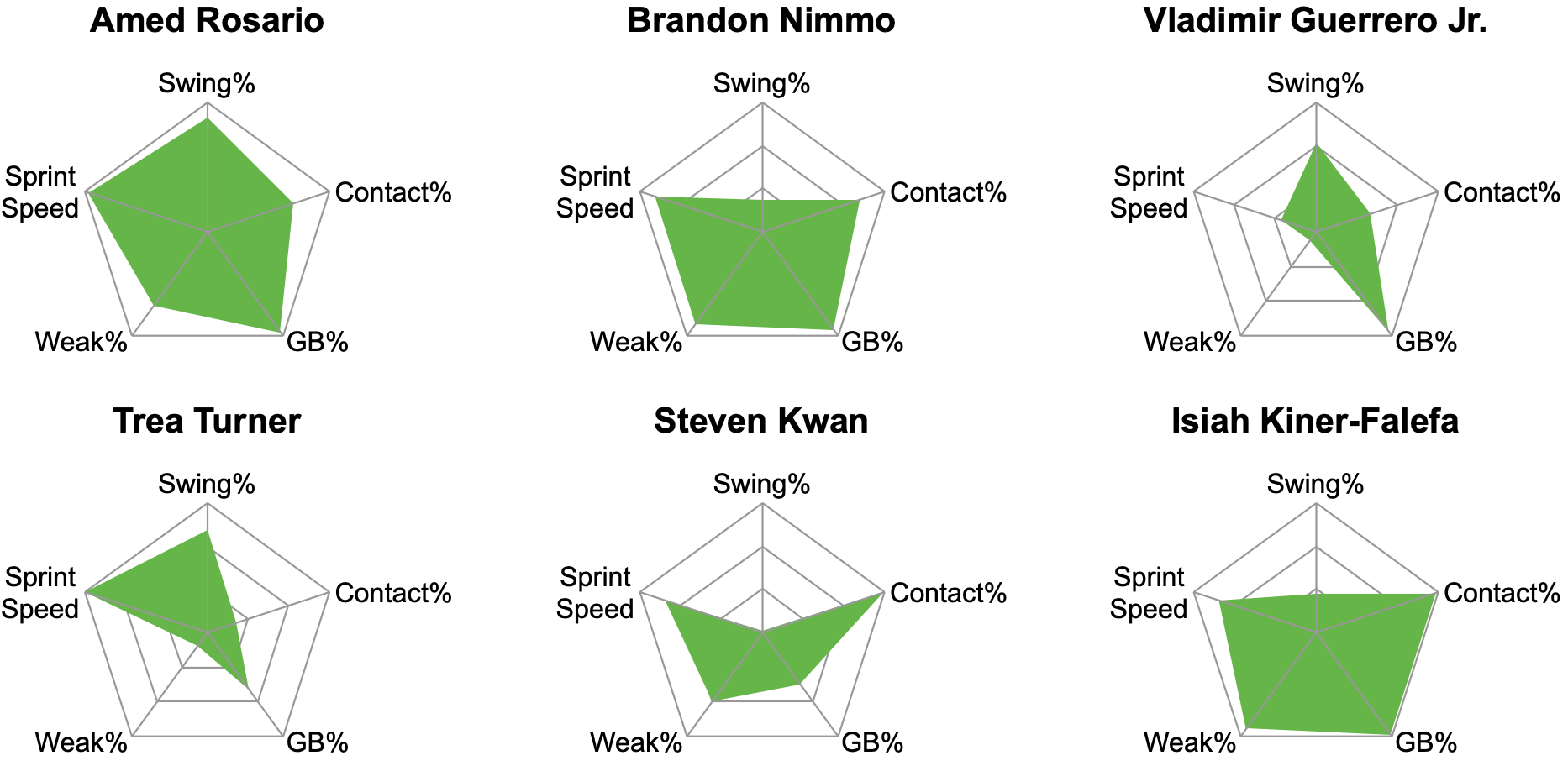

If you were to design a player for the express purpose of accruing competitive runs, they might not be exactly like Rosario, but they’d probably be a close relative. Our hypothetical player — let’s call him Amed Brosario — would need tons of grounders and weak contact. He’d also need to put the ball in play all the time. That means swinging a lot to avoid walks and making contact to avoid strikeouts. I know it sounds like I’m describing a terrible hitter, but Amed Brosario can’t be bad. He has to be good enough to rack up plate appearances by hitting at the top of the lineup every day. In order to make that profile work, he’s got to be fast enough to take extra bases and turn all those weak ground balls into infield hits. Here’s how the real-life Rosario and his closest competitors stand by these metrics:

Rosario is the only qualified player above the 70th percentile in all five categories. Kwan, Nimmo, and Kiner-Falefa are all too choosy, and for some bizarre reason, Guerrero and Turner insist on hitting the ball both hard and frequently. Several players would have had fuller charts than Rosario’s, but none of them played well enough to earn an everyday spot, let alone match his 670 plate appearances. CJ Abrams and Esteury Ruiz (should he start the season in Oakland) could have a real shot at leading the league next year, especially since they’ll be playing for the Nationals and A’s, who won’t have replacements waiting in the wings should they struggle.

Rosario finished the season with a career-best 102 wRC+. Despite his tendency toward weak contact, his hard-hit rate and average exit velocity were both around the 40th percentile. Contributing on the bases and playing a passable shortstop allowed him to put up his second consecutive year with 2.4 WAR.

Rosario makes the very most of his speed, too. He’s tied for 23rd in both sprint speed (29.5 feet per second) and home-to-first time (4.17 seconds), and he stole 18 bases and led the league with nine triples. While his 52.5% groundball rate was fourth highest in the league, he beat out 23 infield hits, second only to Trea Turner. That kept his wOBA on groundballs at a non-disastrous .262, putting him in the 87th percentile of all players with at least 100. Here’s Yoán Moncada realizing far too late that a there’s no such thing as a routine groundball when Rosario is at the plate:

Rosario was also on the perfect team. You can get a competitive run by going from first to third or from first to home, so it helps to have players who put the ball in play behind you in the lineup. Rosario led the league with 134 singles, and the Guardians led the league with 4,510 balls in play. He spent most of the season batting second (whether he should have been that high in the lineup is its own conversation), with José Ramírez batting third, a combination of Oscar Gonzalez and Josh Naylor batting fourth, and Andrés Giménez or Gonzalez batting fifth. All five of them put the ball in play at least 69.8% of the time; Ramírez was at 79.4%, and he hit an AL-leading 44 doubles (Rosario was on base for 11 of them).

According to the baserunning stats at Baseball Prospectus, Rosario was 29th in the league with 145 total opportunities for advancement on the basepaths. He made the most of his opportunities: Per Baseball-Reference, he took the extra base 60% of the time, good for 10th in the league, and got thrown out on the bases 11 times, fourth-most in the league. I watched all 11, and I’d only call one of them truly egregious. Four were just plain unlucky, and another four were exactly the kind of fun, aggressive play you’d expect from the league’s foremost competitive runner:

Rosario has 1,229 career competitive runs. Since his first full season in 2018, his 1,164 are the most in baseball, but this is the first time he’s ever led the league.

| All-Time Leader | CR | Single Season Leader | CR | Year | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DJ LeMahieu | 1,978 | Dee Strange-Gordon | 349 | 2017 | |

| Jose Altuve | 1,975 | Amed Rosario | 342 | 2022 | |

| Xander Bogaerts | 1,938 | Ben Revere | 330 | 2015 | |

| Jean Segura | 1,912 | DJ LeMahieu | 327 | 2017 |

While Rosario has always been in the mix, the real reason he finally took it home in 2022 is that he dropped his strikeout rate to a career-best 16.6%. His walk rate also fell to 3.7%, third worst in the league. That’s not exactly ideal, but as this point I don’t really think we can blame him for preferring running to walking.

Rosario does a whole lot of things right at the plate, only for his upside to be limited by his aggressiveness and a launch angle that is almost literally abysmal. An Amed Rosario with league-average swing and groundball rates would be a star, but I don’t think anybody’s still waiting on such a change. His offensive profile may not be optimal for his overall batting line, but it does pad one particular stat. Besides, it makes it even more fun to watch him run.

Davy Andrews is a Brooklyn-based musician and a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @davyandrewsdavy.bsky.social.

Based on the title, I was expecting a vroom vroom guy cameo.

I’m amazed Forest Gump isn’t mentioned