Another Way To Think About Pull Rate

Every time I watch Oneil Cruz hit, I end up thinking about pull rate. It seems like he’s always using his long arms to yank a ball into right field even though the pitch came in all the way on the outside corner. I’m not quite right, though. According to our leaderboards, Cruz ranks 35th among all qualified players in pull rate. According to Statcast, he’s at 55th, not even in the top third. Maybe it’s just that seeing someone do something as bonkers as this can warp your perspective:

But there is more than one way to think about pull rate. Sometimes you get jammed. Sometimes you have to hit the ball where it’s pitched. Sometimes the situation demands that you shorten up and sell out for contact. Those three examples might tell us a bit less about the intent behind your swing, because you didn’t get to execute your plan. We have ways to throw them out. Today, we’ll look into players whose overall pull rate is notably different from their pull rate when they square up the ball. As a refresher, Statcast plugs the respective speeds of the ball and the bat into a formula to determine the maximum possible exit velocity, and if the actual EV is at least 80% of that number, it’s considered squared up.

I pulled numbers from 2023 through 2025 for each player who has squared up at least 250 balls during that stretch. As you’d expect, the numbers are mostly pretty similar. Of the 219 players in the sample, 165 of them have a difference between their overall pull rate and their squared-up pull rate that’s below three percentage points. No player has a pull rate when squaring the ball up that’s more than 6.5 percentage points off their overall pull rate, but there are a few interesting names here.

| Player | Overall | Squared Up | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oneil Cruz | 39.2 | 45.7 | 6.5 |

| Anthony Volpe | 36.5 | 30.8 | -5.7 |

| Wilyer Abreu | 42.9 | 48.4 | 5.5 |

| Willi Castro | 40.2 | 45.5 | 5.3 |

| Carlos Santana | 50.3 | 55.5 | 5.2 |

| Joc Pederson | 46.4 | 51.6 | 5.2 |

| Keibert Ruiz | 46.6 | 51.8 | 5.1 |

| Eugenio Suárez | 47.6 | 52.7 | 5.0 |

| Salvador Perez | 43.2 | 48.2 | 5.0 |

There’s Cruz at the very top, so maybe I wasn’t totally off base. When he squares the ball up, his pull rate is 6.5 percentage points higher than his normal pull rate. It makes sense, as several of the players on the list are power hitters with big swings and low squared-up rates. The same long levers that allow Cruz to pull the ball even when it’s in the right-handed batter’s box also make it hard for him to catch up to anything on the inside part of the plate. As a result, he catches the ball deeper and sends it the other way. Whether you’re Eugenio Suárez, Joc Pederson, or Salvador Perez, big swings tend to be slow swings, which result in deeper contact points that can depress pull rates.

Anthony Volpe is second on the list. Only Cruz has a bigger gap between his squared-up pull rate and his overall pull rate, but Volpe’s gap is even more notable because he’s the only player in the top 10 who pulls the ball less when he squares it up. In our sample, there are 16 players with a pull rate that’s at least three percentage points lower than their overall rate, while there are 42 players with a gap that big going the other way. What’s interesting is that Volpe doesn’t run particularly high contact or squared-up rates. His overall pull rate is low, but nowhere near the bottom of the league. Those facts seem to be disguising just how much his swing is designed to send the ball the other way. Maybe it’s all that time he spent watching Derek Jeter as a child, but it seems like he has the approach of Luis Arraez, just without the excellent contact ability.

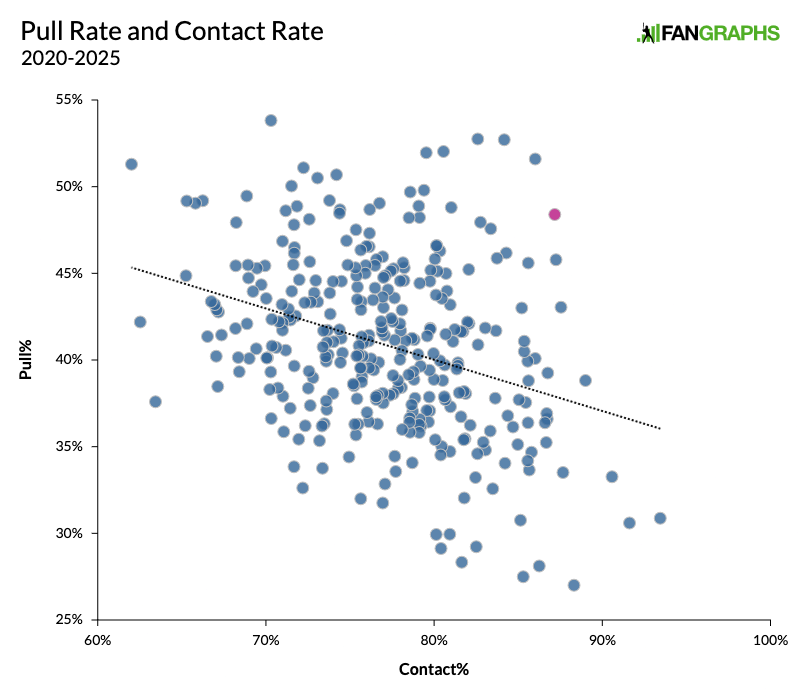

The name I find most interesting is Keibert Ruiz. He stands out nearly as much as Volpe. Ruiz is a switch-hitter and a classic contact guy. Since the deadline deal in 2021 that made him the Nationals’ everyday catcher, he has routinely posted some of the lowest exit velocities and the highest contact and squared-up rates in the game. That combination often comes with a lot of balls hit to the opposite field. Only a handful of players make as much contact as Ruiz while pulling the ball so often. He is the lonely purple dot below.

The players who both pull the ball and make lots of contact tend to fall into a couple specific groups. I took pull rate and contact rate for all qualified hitters dating back to 2020, converted each number into a percentile rank, then added them together. Here are the hitters at the very top.

| Name | Pull% | Contact% | Sum |

|---|---|---|---|

| José Ramírez | 98 | 95 | 194 |

| Keibert Ruiz | 92 | 98 | 190 |

| Isaac Paredes | 99 | 89 | 188 |

| Jose Altuve | 100 | 85 | 185 |

| Alex Bregman | 85 | 98 | 182 |

| TJ Friedl | 90 | 88 | 178 |

| Vinnie Pasquantino | 84 | 94 | 178 |

| Nolan Arenado | 91 | 86 | 177 |

| Wilmer Flores | 86 | 90 | 176 |

With the exception of Ruiz, all the players at the top of the list are lift-and-pull gods with swings designed to break xwOBA. José Ramírez, Alex Bregman, Isaac Paredes, and Jose Altuve don’t hit the ball all that hard, but because they pull everything in the air, they access way more power than you’d expect. Ruiz doesn’t fall into that group at all. He just rolls over tons of balls. Since 2023, 29.5% of the balls Ruiz has put into play have gone to the pull side and been hit under 95 mph. That’s the 14th-highest mark in our sample.

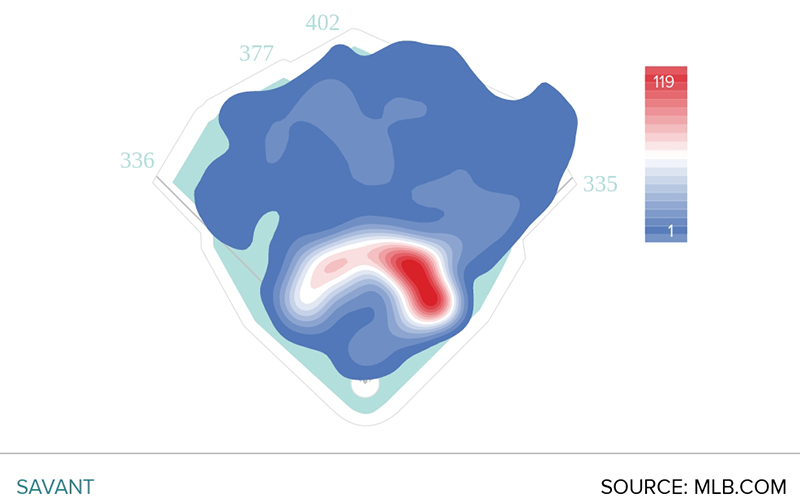

If you start watching tape of Ruiz’s swing, the word “easy” will quickly pop into your head. His swing looks downright languorous. We talk a lot about where a player’s bat “meets” the ball, and that’s an odd word to use when describing a high-speed collision. Ruiz is one of the few players for whom it’s apt. His bat looks like it’s moving slowly enough that it has time to introduce itself to the ball and ask where it’s from. Ruiz crushes this ball, nearly over the fence, but the swing is unbelievably easy.

He starts his swing early and utilizes impressive bat control to take it through the zone extremely slowly. It’s not a standard approach and it hasn’t yielded great results. This season, Ruiz is running the highest groundball-to-fly-ball rate of his career. He currently has a 98 wRC+, and it’s that high at least partly because his BABIP is 68 points higher than his career mark. If he keeps it up, it will be the best full season of his career at the plate. Just two of his 41 hard-hit balls have qualified as barrels. If there’s any player who could benefit from an approach change, it’s Ruiz.

He’s already excellent at squaring up the ball. Maybe he should follow the lead of players like Steven Kwan and Arraez, letting the ball get deep and shooting line drives to the opposite field. Maybe he should follow the lead of Bregman and Paredes and intentionally attack the ball out in front in order to lift it in the air. It’s at least possible that his contact skills will translate to either of those two approaches. Ruiz possesses a rare gift for contact, made all the more impressive because that gift is often reserved for players who give themselves a better chance at making contact by letting the ball travel and sending it the other way. It might be time to see how else he can make the most of these skills.

Davy Andrews is a Brooklyn-based musician and a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @davyandrewsdavy.bsky.social.

When one of the writers here pointed out that swings tend to increase in speed as the swing progresses, which means that hitting the opposite way will result in a lower number, I kind of lost interest in the metric. I want hitters who blast it the opposite way!

I watched the free MLB game between the Phillies and Cards. Christopher Sanchez against Ivan Herrera. First match-up, Sanchez works the count to two strikes and then drops in his devastating change. Herrera goes down on strikes, out in front by two feet. Sanchez is mixing fourseamers in on the hands with change-ups down and away, and painting the corners. Next time up, Herrera is determined to not whiff on the change-up, so he is timing his swing for it. He makes contact with every pitch. He is late on every inside fourseamer but fouls them all into the stands down the first base line. He can’t square up the change-ups but fouls all those down towards his feet. Eventually Sanchez misses a few times and Herrera takes a walk. Third time up, Herrera is still timing the change-up. But this time one of the fourseamers leaks out over the plate. Herrera is still way late, but it doesn’t matter, because he barrels the ball the opposite way for a home run.

I would much rather see this than a hitter trying to pull an outside pitch.