Adventures in Extreme Plate Discipline

How do you have non-existent power (second worst in baseball), an average BABIP and still provide above average offensive value? One way is to walk 2.39 times for everytime you strikeout like Luis Castillo has done so far this year. Luis Castillo is leading the league in BB/K, a little bit higher than Albert Pujols.

Castillo does it by swinging at nothing. He has the second lowest O-swing rate to Marco Scutaro and by far the lowest Z-swing rate, the only player under 50%. Throw Luis Castillo a pitch in the zone and he is more likely to take it than swing at it. When he does swing he makes contact over 94% of the time, tops in the league.

Effectively Castillo is just waiting for the pitcher to walk him. Taking almost all pitches out of the zone, over half of them in the zone and hoping to accumulate enough balls for a free pass. When he does swing he almost always makes contact, so he rarely strikes out. I wanted to see how it does it. First I looked at how often his swings by the number of strikes.

Swing Rate +----------+-----------+-----------+ | Strikes | Castillo | Average | +----------+-----------+-----------+ | 0 | 0.129 | 0.291 | | 1 | 0.322 | 0.489 | | 2 | 0.536 | 0.600 | +----------+-----------+-----------+

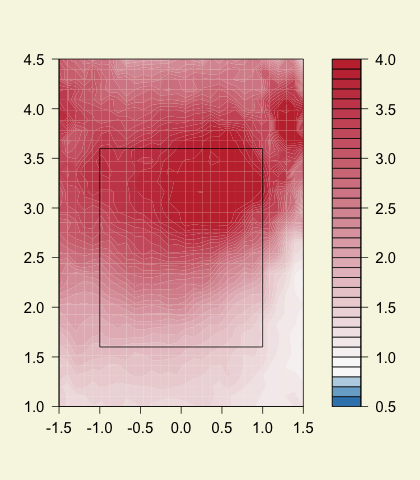

So his difference from average is the largest early in the count. By the time he has two strikes he swings at about league average rate, which is how he keeps his strikeouts down. Let’s see what that looks like in terms of his swing contours. Castillo is a switch hitter but I plotted just his at-bats as a lefty and compared him to other lefties. Recall that I am plotting his 50% swing contour, that is inside the contour his swing rate is greater than 50% and outside less. Additionally for zero strikes I also plotted the 25% contour. Right along that contour he swings 25% of the time, inside of it greater than 25% of the time and outside less.

With no strikes Castillo doesn’t have a 50% contour. There is no location where he is more likely to swing at a pitch than not when he has no strikes. In fact his 25% swing contour is about the same as the average lefty’s 50% swing contour. So he is about half as likely as the average lefty to swing at a pitch down the middle of the plate. As he gets more strikes his contour looks more and more like the average lefty. With more strikes he starts to swing more, since he doesn’t want to strike out looking.

Since he has no power and very rarely swings at pitches out of the zone opposing pitchers have no reason to throw him anything but strikes. His in zone percentage is high, 51.6%, but there are lots of batters higher. J.J. Hardy, Colby Rasmus, Mike Cameron, B.J. Upton and Yunel Escobar, among others, all see a higher percentage of strikes. So pitchers should have the ability to throw him a higher percentage of strikes than they are. I think this is probably because Castillo usually bats in front of the pitcher, while those guys in front of power hitters. Even so you have to think pitchers are making a mistake. The currency of the game is outs, and at-bats to Castillo could be ending in outs more often than they do.

EDIT: I stand corrected, Castillo has led off 14 times, batted 2nd 26 times and 8th 23 times. Based on this there is no one excuse for pitchers not pounding it in the zone 55% of the time like they do against David Eckstein, Willy Taveras and Jason Kendall.

I think most people view Castillo as a pretty boring player, but he is able to provide above average offensive value with no power and a diminishing ability to beat out grounders (his value used to come from an above average BABIP). I think that is cool, he can take extreme plate discipline, and little else, and make it work.