Mauer’s Performance by Pitch Location

Playing around with the new splits yesterday Dave C. noted Joe Mauer’s bizarre spray chart numbers. To right field Mauer hits ten grounders for every fly ball and Mauer’s ISO and wOBA by direction in play resemble a RHB more than a LHB peaking in left (opposite field for Mauer) and smallest in right (pull field for Mauer).

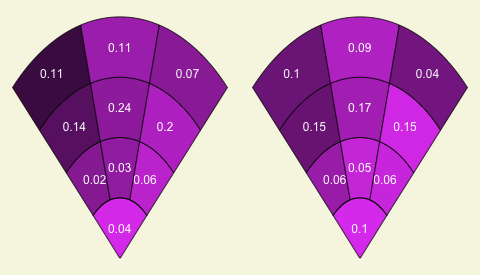

Some commenters to Dave’s article questioned how Mauer handled pitches to different parts of the plate, and whether that was responsible for this pattern. I thought these were very interesting questions. I plotted the average angle of his grounders and balls in the air based on the horizontal location of the pitch. I show the average lefty for comparison. Here -45 corresponds to the left-field line, 0 to second base and dead center, and 45 to the right-field line.

Not surprisingly all of the lines are increasing, the farther inside a pitch is the more it is pulled (greater angle meaning farther to right field). For LHBs grounders are, on average, pulled while balls in the air depend on the pitch location: inside pitches hit in the air go, on average, to right while outside pitches go to left. I have previously shown this with the HITf/x data and Matt Lentzner has a simple, but very cool, bat-ball collision model that shows why this is the case. Anyway Mauer’s ground balls are not all that different than the average lefty’s, but his balls in the air are. No matter where the pitch is Mauer, on average, hits balls in the air to left field. Even on far-inside pitches the average fly ball Mauer hits will be to center-left. This is how he ends up with all his pulled hits as grounders.

This backs up Dave’s suggested defensive alignment, “teams should consider employing two different shifts against Mauer; an outfield shift playing him as if he was a pull-heavy right-handed batter, and an infield shift treating him as a pull-heavy left-handed hitter.”

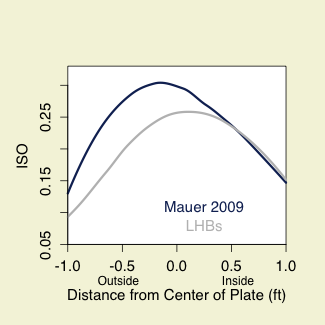

How does this affect how well he does on those pitches? Here is Mauer’s and the average LHB’s ISO by horizontal pitch location.

The average lefty has the most power on pitches middle-in and on such pitches Mauer has about average power. But Mauer’s power keeps increasing as pitches get father away from him and peaks middle-away. On pitches on the outer half of the plate Mauer has substantially more power than the average lefty. Since Mauer is going the other way with his fly balls anyway it makes sense that he would do best on pitches slightly away.

Taro, a commenter to Dave’s post, noted maybe it would be best to pitch Mauer inside, where he has just average power. Have pitchers adapted against Mauer and thrown more inside pitches to him?

Doesn’t seem so; in fact if anything pitchers pitch even farther away to Mauer than they do to the average lefty. It looks like faced with the already Herculean task of trying to get Mauer out pitchers are not doing themselves any favors with their approach. It will be interesting to see if that changes this coming season.