Can Ryan Helsley Actually Start, or Are We Just Not Eating Enough Protein?

All relief pitchers are failed starters. In the future, everyone will be world famous for 15 minutes. All great world-historic facts and personages appear, so to speak, twice… the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce.

Therefore: In the future, all relief pitchers will be starting pitchers for 15 minutes, twice: First as failure, then as tragedy.

This jumble of aphorisms is what plopped out of my head when I read a bit of surprising news: The Detroit Tigers are interested in Ryan Helsley — reasonable enough, since he’s been a good high-leverage reliever for several years — as a starting pitcher.

Whoa.

That’s not all. The Athletic’s trio of credited writers — Ken Rosenthal, Cody Stavenhagen, and Katie Woo — used the following phrasing: “The Detroit Tigers are among the clubs talking to the free-agent right-hander about becoming a starter.” (Emphasis mine.)

How serious those talks are, I don’t know. Maybe one of the GMs butt-dialed Helsley’s agent and, rather than admit to the mistake, went, “Hey, does your guy think he can start?” Even if that’s the case, it’s out there as an idea now, so let’s investigate it.

I feel like my initial skepticism about this idea is showing, but I absolutely get why the Tigers or any other team might try to shoot the moon. Reliable starting pitching is rare, and accordingly expensive. Relief pitchers — even really good ones, who throw 100 mph and have low-2.00 ERAs and 30% strikeout rates in the recent past — are relatively cheap.

Our free agent predictions have starters like Lucas Giolito, Tyler Mahle, and Chris Bassitt going in about the same $14 million to $16 million range as big-name elite relievers like Devin Williams and Robert Suarez. If you want to drop down a tier to guys who are pitchable in the playoffs but maybe not lights-out, Emilio Pagán and Seranthony Domínguez are available in the $7.5 million to $8 million range.

We have Helsley — whose stock got bruised when he was traded to the Mets and suddenly couldn’t hold a lead — down for two years at $10.8 million per. At $11 million a year, even 130 league-average innings would be the kind of bargain that would inspire any dad to call everyone he knows to brag about how well he made out at the flea market on Saturday morning.

Would Helsley be willing to try? You’d have to ask him, though I imagine he could be enticed to give starting a shot if the money and situation were right. The big question is whether it can work.

According to Stathead, in the past 10 years, 289 active pitchers have recorded at least one season in which they made 15 or more starts, with those starting appearances accounting for at least 60% of their total games pitched. In the same time period, 344 pitchers have at least one season of 40 or more relief appearances, with at least 90% of their appearances coming out of the ‘pen. There are 44 pitchers who show up on both lists.

About three quarters of those are, as I mentioned before, failed starters. A few others took the Adam Wainwright route: Top starting pitching prospects who were reassigned to the bullpen for reasons of temporary expediency, then re-converted to the rotation. Garrett Crochet is the most famous of these by far, though I’d classify Matthew Liberatore this way as well.

Several pitchers have floated back and forth between the bullpen and the rotation because they’re replacement-level anywhere, and end up pitching wherever and however innings are needed. Some of those (Ryan Yarbrough, Brent Suter) are occasionally better than replacement-level. Either way, the soft-tossing lefty is roughly the opposite of Helsley, so they’re not useful as a comparison.

Zack Littell and Andre Pallante are borderline cases; both were starters as prospects, pitched a lot out of the bullpen early in their major league careers, and have since been restored to the rotation. It’s not quite the Helsley story here.

That leaves us with three archetypes of bullpen-to-starter conversion: First, Royals guys who throw a million types of pitches. Seth Lugo is far and away the most successful of these, but Michael Lorenzen counts here, and don’t look now, but Stephen Kolek had a 1.91 ERA in five starts after he was traded to Kansas City last season. All of those guys had significant starting experience in the pros; Lugo and Lorenzen had both been yanked from one role to the other a few times.

This is not Helsley, who hasn’t started a game at any level since 2019, and who throws almost exclusively fastball-slider.

The second archetype is Jeffrey Springs, who started almost exclusively in his last three years at Appalachian State, then almost not at all in his first eight professional seasons. When Tampa Bay gave him his first start in April 2022, Springs had to that point made 107 relief appearances in the majors for three teams, and only two starts — neither longer than three innings or 44 pitches. In parts of five minor league seasons to that point, Springs had made 120 appearances, only 28 of them starts.

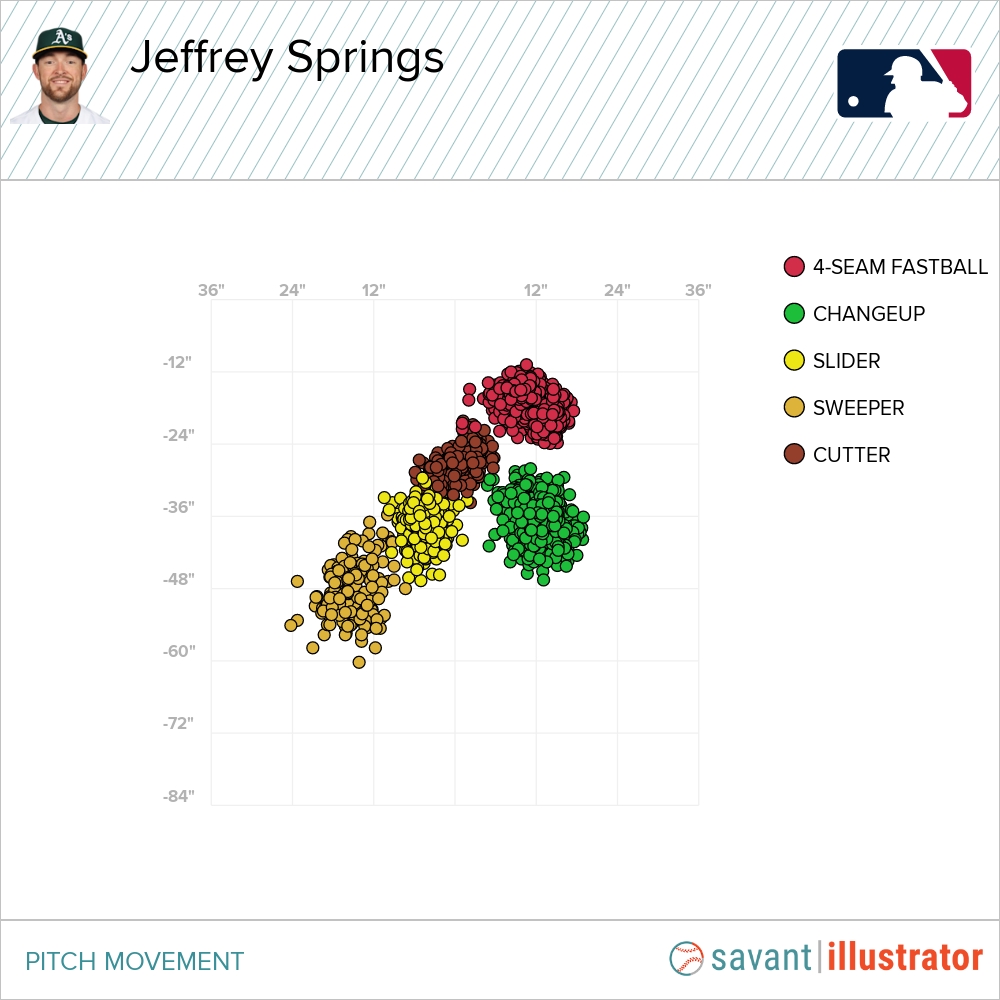

There’s another key difference between Springs and Helsley, which I’ll come back to in a second. You know, apart from Springs throwing 90 and being left-handed and Helsley throwing 100 and being right-handed.

The third archetype is the power bullpen arm: Clay Holmes and Reynaldo López have been successes, while Jordan Hicks has not.

Holmes and Springs are wildly different as pitchers, but they share an ability to work laterally. His last season as a reliever, Springs threw a four-seamer with some rise and arm-side run, along with a changeup to lefties and a slider to righties. He’s tinkered a little with adding some other pitches, but that’s still the core of what he’s about. You can see here the broad variety in horizontal movement among the pitches he throws:

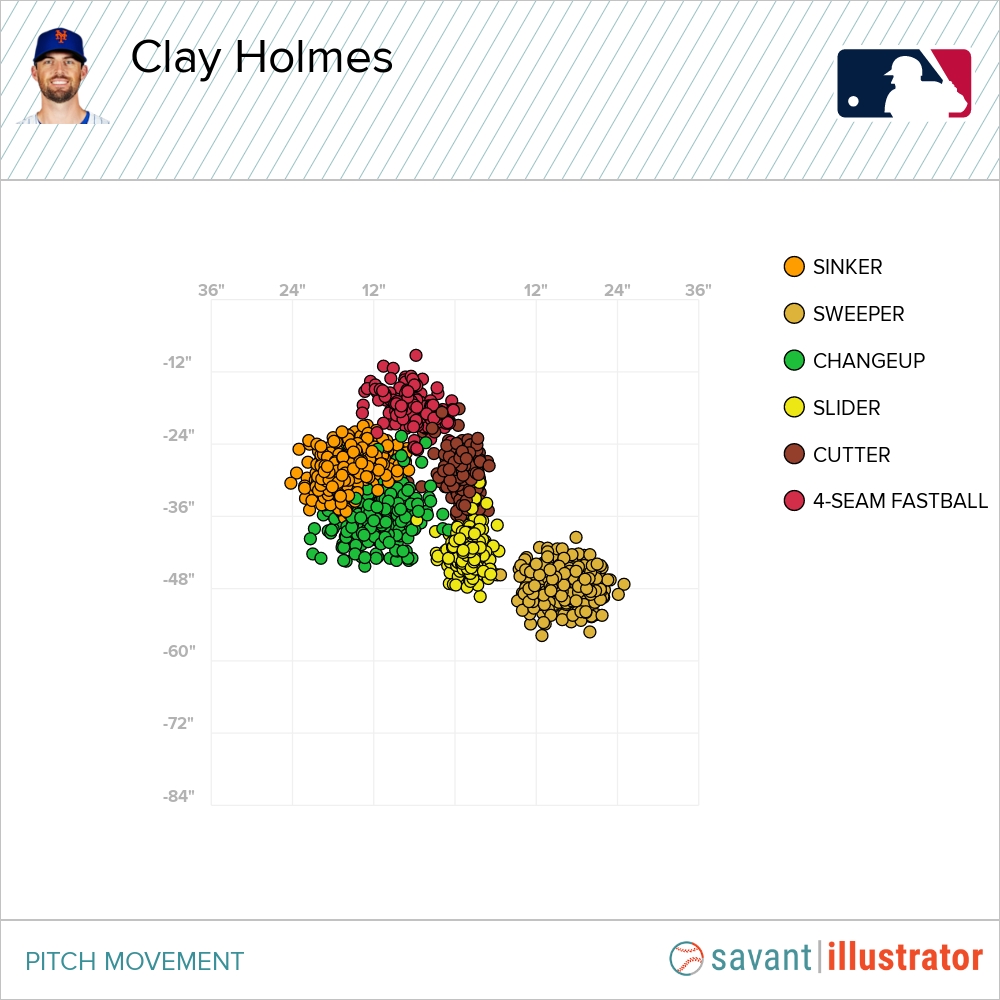

Holmes is a sinkerballer, always has been. When he was throwing out of the bullpen, he mixed in two breaking balls: a slider, which had arm-side movement and came in slower than his swinker; and a sweeper, which is like the slider, only more so. This made him the biggest groundball machine in the league, and it worked against hitters on both sides of the plate.

As a starter, Holmes has added a variety of other pitches — a changeup to get lefties out, a cutter, even a four-seamer — but again, it’s still a lot of horizontal movement variation:

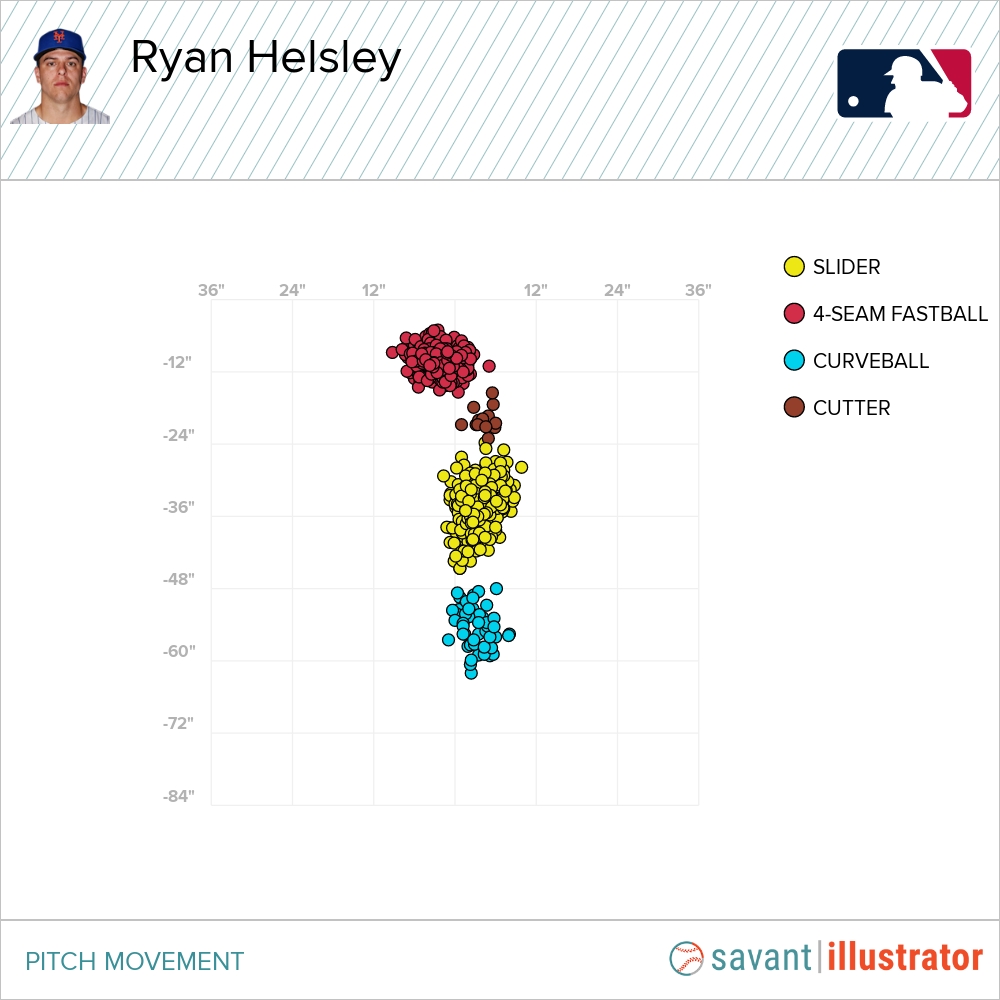

If you wanted to, you could describe both Helsley and pre-2025 Holmes as fastball-slider guys, but that’d be so misleading as to be mischievous. In contrast to the three-quarters arm angles used by Holmes and Springs, Helsley comes over the top. His fastball has more cut to it than anything, and his slider — rather than whirling away from righties — goes straight down the elevator shaft:

There are plenty of starting pitchers who beat wholesale ass with a fastball that has this kind of movement, but they need something extra that Helsley doesn’t have. Cade Horton has more extreme cutter action than Helsley, in addition to a changeup and sweeper that allow him to work horizontally. Kyle Bradish throws a sinker. Tyler Glasnow has a sinker, a slow curve, and best-in-baseball extension with his big ol’ spider crab limbs.

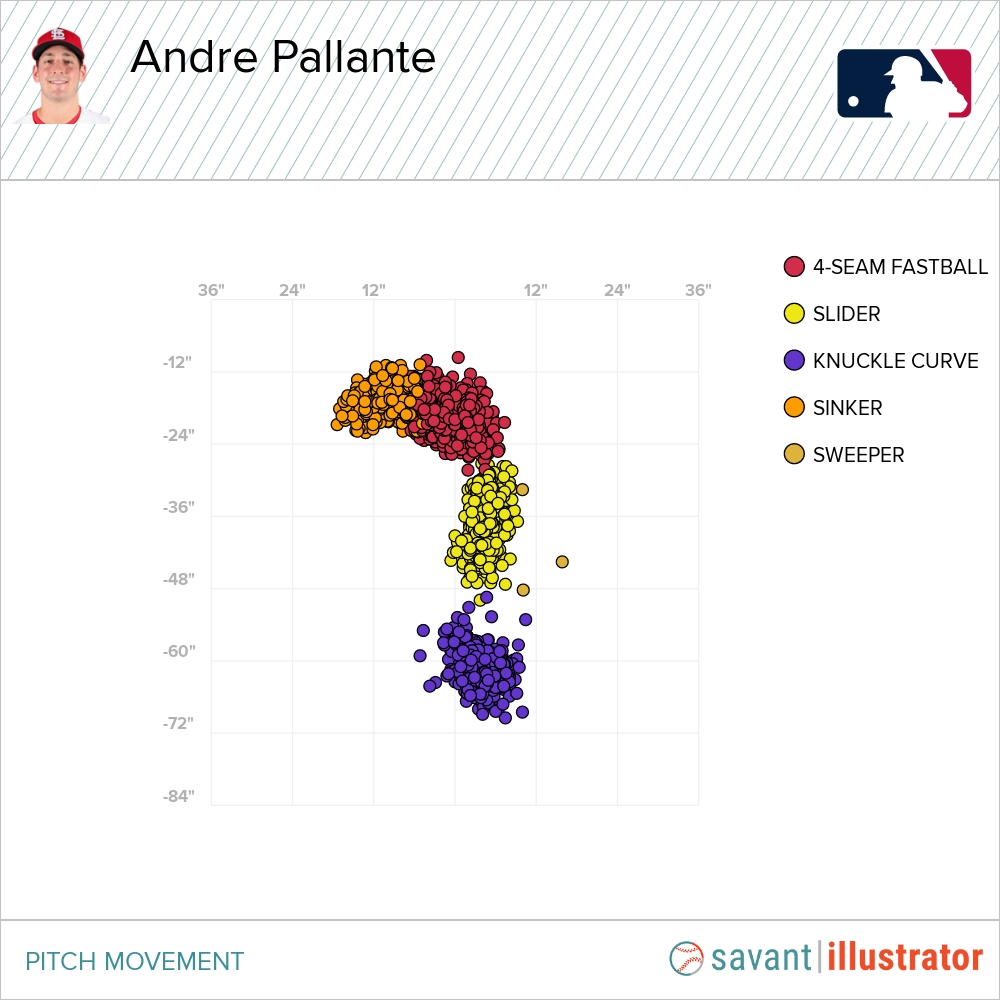

Actually, you know who does work in a narrow horizontal band like Helsley? His old teammate, Pallante:

That sinker is his least-used pitch. But I’m not sure Helsley wants to emulate Pallante, who had a 5.31 ERA and 4.86 FIP this past year.

Instead, López might be the guy to emulate here. His fastball-slider combo does have more horizontal separation — they’re more like Spencer Strider’s than Helsley’s. But he managed, at least for most of one season, to be one of the best starters in baseball almost exclusively as a four seamer-breaking ball guy.

But López’s four-seamer is a weapon, both out of the bullpen and out of the rotation. Opponents wOBA’d .301 off it in 2023, and .319 in 2024. Helsley, for all his diabolical four-seamer velocity, got his heater knocked around to the tune of a .506 wOBA in 2025.

So something has to change if Helsley’s going to be able to hack it out of the rotation. He’s going to need to add a sinker or a changeup or rework his breaking stuff. And that’s assuming he can hold up to the physical challenge of starting 25 or 30 games and more than doubling his workload. I hope, for everyone’s sake, that if Helsley does sign as a starter, his new team knows what it’s doing.

Michael is a writer at FanGraphs. Previously, he was a staff writer at The Ringer and D1Baseball, and his work has appeared at Grantland, Baseball Prospectus, The Atlantic, ESPN.com, and various ill-remembered Phillies blogs. Follow him on Twitter, if you must, @MichaelBaumann.

This is good stuff! It feels weird seeing Lopez counted as “just” a power bullpen arm after watching him struggle to lock down a rotation spot on some pretty mediocre White Sox teams, but it does make sense with the way it’s laid out.