Catcher Blocking Is Still The Wild West

The doldrums of the offseason induce fascinating research. Look no further than Ben Clemens’ post “They Don’t Make Barrels Like They Used To,” or Davy Andrews’ follow-up, “They Don’t Make Pitch Models Like They Used To.” When the free agent signings dry up, baseball writers must get real creative. And so they write about stuff like the Competitive Advantage Life Cycle.

In his pitch models piece, Davy outlined in four bullet points what happens when one team gains an edge over the others:

- Teams realize the immense value of a skill.

- An arms race ensues as they scramble to cultivate it.

- The skill becomes widespread across the league.

- Since the skill is more evenly distributed, it loses much of its value.

“The second we gained the ability to calculate the value of catcher framing, everybody started working on it,” he wrote. No longer was Ryan Doumit allowed to work behind the plate once it became clear he was capable of leaking 60 runs of value in a single season. Davy produced this helpful plot to demonstrate this convergence of catcher framing value, the Competitive Advantage Life Cycle in action:

All the teams are smart now. Even the Rockies might be smart! Even in areas that ostensibly look like pockets of inefficiency — reliever contracts, for example — there is likely some sort of internal justification for the behavior. Once something can be quantified, the serious outliers disappear. Right?

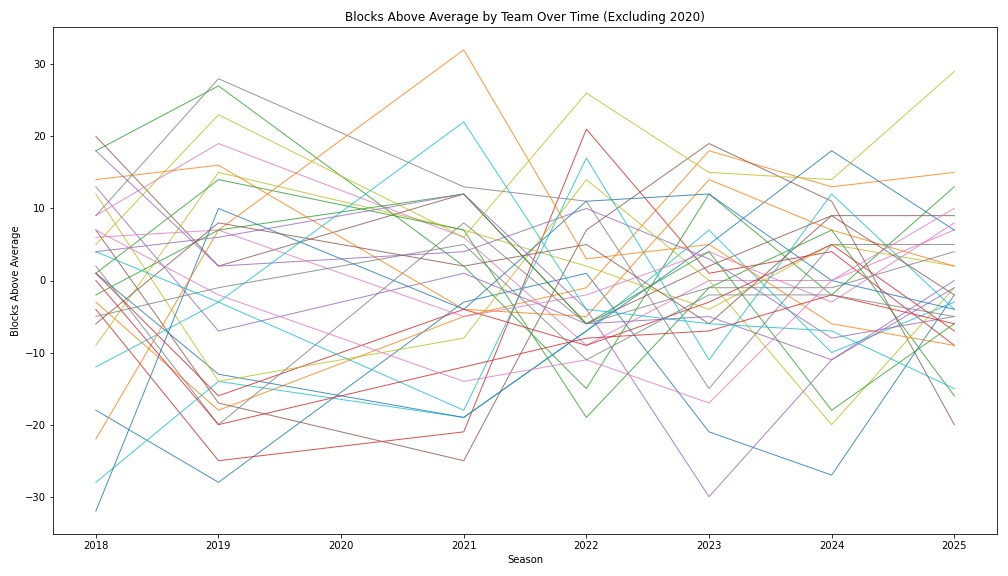

Maybe not quite. Three years ago, catcher blocking statistics surfaced on Baseball Savant, though teams surely were measuring this skill internally for years prior to its public introduction. Has there been a general convergence in the years since? To some degree, yes. Here is the blocking equivalent of Davy’s plot, with Savant’s “blocks above average” metric on the y-axis. There isn’t a clear clustering trend like in the framing case, but the middle of the pack appears a touch tighter.

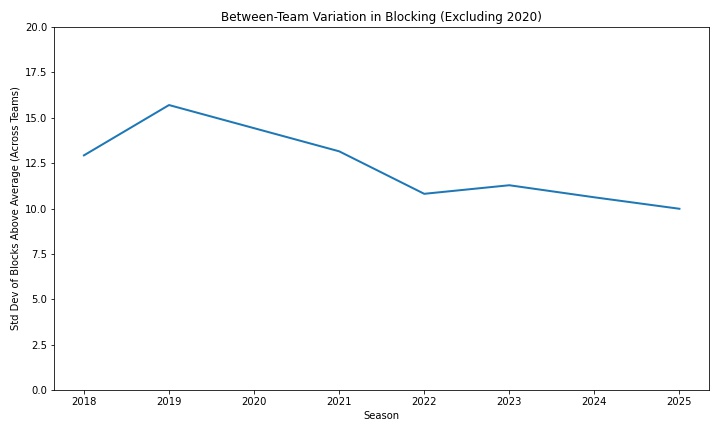

Measured as the standard deviation between teams, the trend is a little clearer. Slowly but surely, teams are beginning to converge.

But the catcher blocking revolution is a tentative one. While it’s moving in the right direction, it’s too soon to say the arms race is fully on. To wit: Last year was the worst catcher blocking season in recorded history.

Though Savant introduced the metric publicly in 2023, they have in the years since provided data going back to 2018. Between 2018 and 2025, there were 538 qualifying catcher seasons. Agustín Ramírez’s -28 blocks below average last year ranked 538th among that cohort. It should noted that blocks above average is not a rate stat; he did all that in just 73 games behind the dish.

The slower convergence on blocking is, I think, understandable. Of all the things a catcher does, it’s among the least sexy. Framing, naturally, has received most of the attention from analysts over the last decade or so; it tends to comprise the plurality of catcher defensive value, even in this phase of the Competitive Advantage Life Cycle. Throwing runners out, meanwhile, gets the most love on broadcasts, and it’s the easiest to spot.

Blocking sort of falls between those two catcher activities. It’s somewhat visible, but the difficult blocks happen relatively infrequently. And the value is muted: Savant estimates each block above (or below) average grades out to a quarter of a run. Even Ramírez’s record-breaking season, then, only resulted in -7 runs of blocking value. By comparison, it isn’t all that remarkable to lose seven or more framing runs; eight catchers bested (worsted?) that mark in 2025 alone.

Additionally, there is not much blocking discourse. What distinguishes a good block from a great block? How much is a block worth? Who is the best at this skill? I don’t think there is a common consensus on these questions.

Defined as it is by Savant, blocking is, in some sense, the fundamental task of catching. Only a subset of all pitches are potentially “framable.” Catching a runner stealing is even less common. But on nearly every single pitch, the catcher must catch the ball. It’s right there in the name! Catcher!

For a full-time catcher, that comes out to tens of thousands of pitches in a single season. Perhaps you are saying, ‘OK, how many of those are actually hard to catch?’ I submit that they all are; professional catchers just make it look easy. Imagine a moderately athletic young person was thrown into a game to catch for nine innings. They’d miss hundreds of pitches. To catch in the major leagues, you cannot miss hundreds of pitches. You need to catch them all.

Compared to the general population, Ramírez is an amazing catcher. He saw thousands of pitches with crazy velocity and mind-bending spin and caught nearly every one. But he did not catch them all. In fact, he made a mess of many catchable pitches in the 2025 season. On Savant, the “blocks above average” statistic is described thusly:

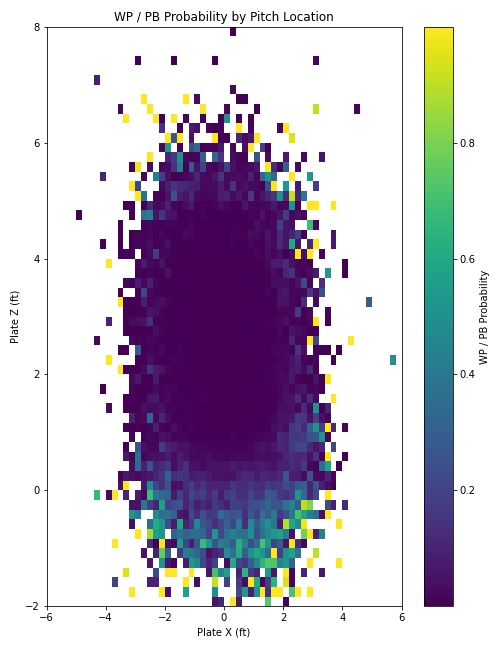

Every pitch is assigned a probability of being a passed ball or wild pitch based upon several inputs, most notably: pitch location, pitch speed, pitch movement, catcher location, and batter/pitcher handedness. Based on that knowledge, each pitch a catcher receives (or fails to) is credited or debited with the appropriate amount of difficulty. For example, if a catcher blocks a pitch that is a PB + WP 10% of the time, he will receive +0.10. If he blocks a pitch that is a PB + WP 90% of the time, he will receive +0.90.

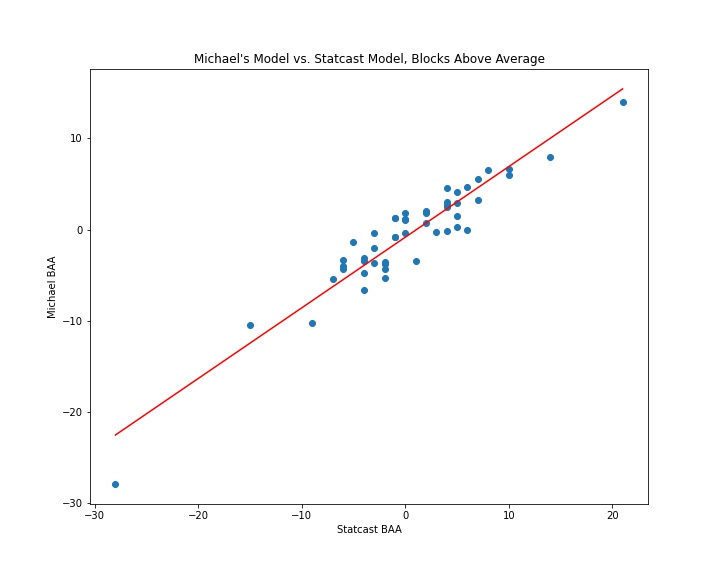

I wanted to better understand what this looked like in practice, so I tried to recreate the Statcast model from scratch and apply it to all the pitches in the 2025 season. I was not privy to some of the inputs of the Statcast model, such as the positioning of the catcher, and my physics knowledge was not robust enough to calculate where a spiked pitch intercepted the ground, as Tom Tango did in this explainer post.

What I do have access to, however, is Python, and a just-good-enough knowledge of machine learning techniques. I started with pitch location, release position, pitch movement, and velocity as my predictor variables. At first, it was terrible. But after some trial and error, I landed on a CatBoost framework, and the resulting model came surprisingly close to reproducing Tango’s model. While it slightly underrated the likelihood of wild pitches, it nonetheless correlated nearly identically with the Savant leaderboard at the individual catcher level (0.9 r-squared).

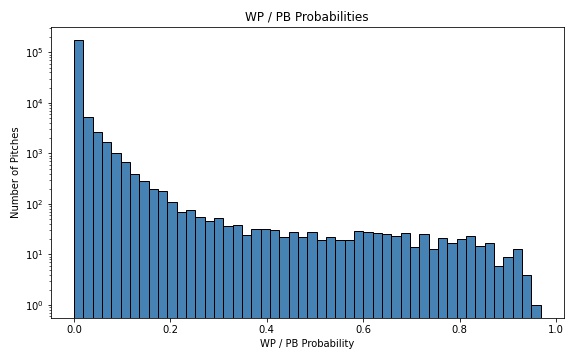

Once I had a good-enough approximation, I set out to better understand the spectrum of wild pitch/passed ball probabilities. Out of nearly 200,000 pitches with runners on base in the sample, just 198 graded out as both a) having a less than 1% chance of being a wild pitch or passed ball, and b) ultimately becoming a wild pitch or passed ball. Here is the general distribution:

Of those 198 extremely unlikely passed balls/wild pitches, 12 can be attributed to Ramírez himself. Funnily enough, he actually graded out as a roughly average framer. But his framing focus, I believe, may have led to some of these inexcusable passed balls. Apologies to the man, but I compiled a reel of his lowlights that can be seen below:

(There is hope yet for Ramírez. Shea Langeliers finished with -26 BAA in 2024; his framing declined in 2025, but his blocking graded out as bang-on average.)

One way to lose lots of blocking value is to whiff on these sorts of catchable offerings, but catchers can make up ground by smothering difficult pitches. Here’s the best block of the year, according to my model, which gave Austin Wells just a 14% chance of corralling this splitter. Leverage isn’t considered here, but it must be noted that this block literally saved the game; the Yankees went on to win in 11 innings:

Wells is a decent blocker, but he is far from the best. That honor goes to Alejandro Kirk, who excels not just at limiting mistakes, but also wrangling unruly breaking balls in the dirt. As this plot shows, the highest probability wild pitches/passed balls live down there:

Kirk is able to smother these types of pitches better than anyone in the league. Watch him make easy work of this 89-mph knuckle-curve in the dirt:

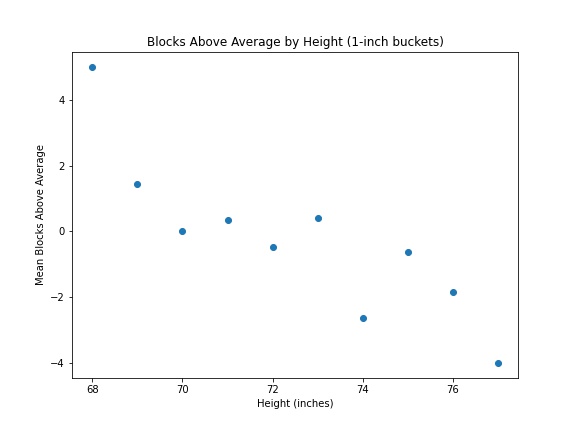

One thing to know about Kirk: He’s short (for a baseball player, anyway.) He’s got a low center of gravity, and he gets down to block those pitches. Does being short help you succeed at blocking? It seems like there’s at least some evidence that’s the case:

For now, Kirk is the reigning king of blocking, and Ramírez its court jester. Give it a few years — say, by 2030 — and blocking will likely find itself in the same place as framing, eliminating itself of Doumit-y characters, anything that reeks of serious lost value. All the mess gets filtered out eventually. As of now, we find ourselves in a purgatorial phase of the Competitive Advantage Life Cycle. Enjoy the imperfections while they last.

Thanks to Stephen Sutton-Brown for technical assistance.

Michael Rosen is a transportation researcher and the author of pitchplots.substack.com. He can be found on Twitter at @bymichaelrosen.

Hard disagree with this sentence.

Blocking is pretty high on the list of sexy things catchers do, right below back picking at first base and casually backhanding a bounced pitch.

Sexy in the capacity of how it’s executed, but not sexy in how it effects the game.

I had the exact same reaction. I couldn’t finish watching the Ramirez videos, because I felt so bad for the guy. The Kirk and Wells videos OTOH are definitely sexy.