Creating a Projection for Munetaka Murakami

What sort of production can we expect from Munetaka Murakami in 2026? This article walks through my steps in creating an MLB projection for the Yakult Swallows superstar.

With one day to go before his negotiation window closed, Murakami and the Chicago White Sox agreed on a two-year, $34 million deal; you can read Michael Baumann’s thoughts on the signing here. Both the dollar amount and the length fall well short of expectations: Ben Clemens projected him to land a seven-year, $154 million contract, while our median crowdsourced contract estimate was for six years and $132 million. Prior to Murakami’s posting, Eric Longenhagen highlighted his 80-grade raw power, as well as his major contact issues, in an October international players update. Both Eric and Ben saw first base as Murakami’s likely defensive home, something the White Sox have already confirmed for the coming season. ZiPS projects him for a .237/.363/.454 triple-slash line and a 126 wRC+. My own projection system, OOPSY, does not yet project NPB players, but that’s something I’m aiming to change with this article. So what might OOPSY expect from Murakami?

The first step in creating a Murakami projection was to review the literature. Previous research from team scouts, analysts, and the creators of other projection system tends to rate NPB as close to Triple-A in terms of its quality of competition. This serves as a good reference point for developing my own quality of competition estimate.

Since the start of last year, FanGraphs has published NPB historical data dating back to 2019. Using this data, I looked at how wRC+, an all-encompassing rate statistic that measures a player’s offensive talent, changed in adjacent seasons for two groups of hitters: players who moved from NPB to MLB, and players who moved from MLB to NPB. I used the delta method to look at the average wRC+ change for each group weighted by the lesser number of plate appearances a player had in the two adjacent seasons. I grouped the NPB Pacific and Central Leagues together for convenience as previous work has rated them similarly in terms of league difficulty.

Here’s how the delta method works, taking Seiya Suzuki as an example: In his final NPB season, he posted a 195 wRC+, followed by a 118 wRC+ in his MLB debut. Of the two adjacent seasons, his 446 plate appearances with the Cubs is the lesser plate appearance number and is the weight given to his 77-point wRC+ change. You could make an additional adjustment to account for aging across the two seasons, but it’d be a trivial adjustment given that transitions between NPB and MLB tend to happen after players are already in their prime. This exercise is repeated for all NPB-to-MLB transitions to find the weighted average wRC+ change for the group. The weighted average wRC+ change can then be used to translate NPB statistics to MLB statistics and incorporate them in a projection as if they were MLB statistics. Translated statistics are often referred to as major league equivalencies or translations.

The first group, NPB to MLB hitters since 2019, consists of only eight players. It includes Masataka Yoshida, Suzuki, Yoshi Tsutsugo, Shogo Akiyama, and some MLB players who left for NPB but then returned, like Alcides Escobar. The weighted average change for this group was a 49-point wRC+ decline upon transitioning from NPB to MLB.

As a robustness check, I also collected Baseball Reference data dating back to 2000 that only covered players leaving NPB for MLB who had never previously played in MLB, thus removing players like Escobar from the sample. Going back to 2000 increased the sample to 19 players. This group saw their wRC+ drop 53 points on average upon transitioning to MLB, a similar finding to the more recent sample.

The second group, MLB to NPB hitters, was larger, at 52 players. It includes players like Franmil Reyes, Trey Cabbage, Franchy Cordero, and Frank Schwindel. This group saw their weighted average wRC+ improve by 32 points upon transitioning to NPB. Compared to the NPB-to-MLB group, this gap is roughly 20 points smaller, suggesting the quality of competition is somewhat closer between the two leagues.

How do we make sense of the different estimates for each group? The more generous 32-point translation suggests the quality of competition in NPB is comparable to Triple-A, in line with conventional wisdom, whereas the harsher 53-point translation suggests it is closer to Double-A. Data on transitions between Triple-A and NPB suggest that NPB is a bit stronger than Triple-A, also aligning more with conventional wisdom, and I have little doubt the the average NPB team would usually beat the average Triple-A team. The steeper 53-point translation may nonetheless arise because of selective sampling. For instance, if a player underperforms his true talent level in NPB, he is unlikely to be given an opportunity to play in MLB. The players who end up receiving an MLB opportunity are typically coming off career-best performances in NPB. They are disproportionately likely to regress somewhat toward the mean in their first MLB season. In theory, this effect would be offset by underperforming NPB players regressing positively toward the mean in their first MLB season, except this group is never given the opportunity. The result is a biased sample that may make the quality of NPB competition look weaker than it is.

In the face of selection bias, which plagues virtually all sabermetric studies, what is a prognosticator to do? You can just listen to scouts, who do not suffer from the same biases, though they of course have biases of their own. However, if your goal is to produce a statistical projection, the only path forward is to make an educated guess that takes previous research into account.

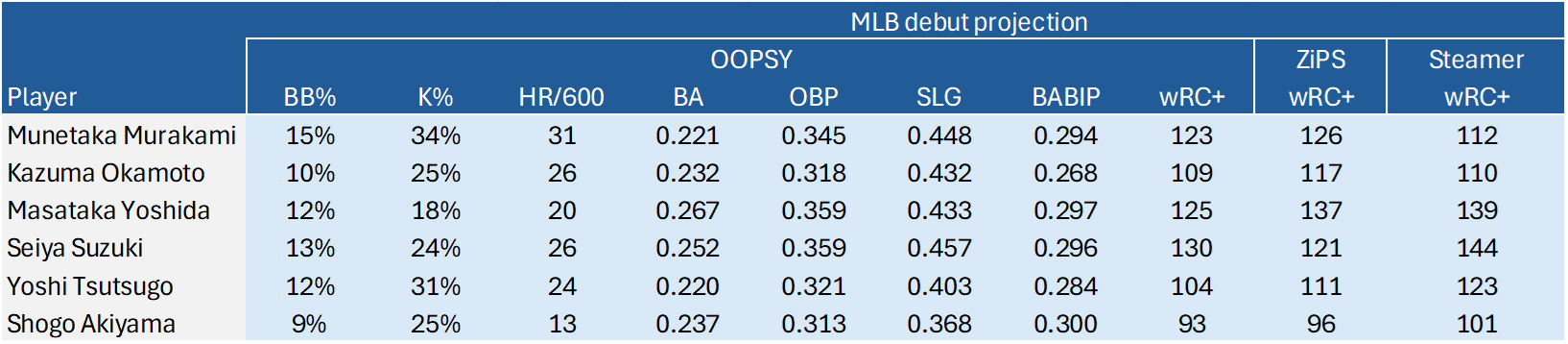

In this spirit, I tinkered with various options for the translations in Murakami’s projection. I also produced projections for our second-ranked NPB hitter in this offseason’s free agent class, Kazuma Okamoto, as well as retroactive projections for the Japanese NPB-to-MLB class since 2019, namely Akiyama, Tsutsugo, Suzuki, and Yoshida. As a reference point, I compared these retroactive projections to historical wRC+ projections from Steamer and ZiPS for each player’s MLB debut. All projections otherwise follow OOPSY’s methodology, weighing recent historical performance more heavily, and accounting for things like aging, league run environment, and regression. Here I’ll note that they do not include bat speed (that data is not yet available, although it might be soon) or contact rate, but the importance of these indicators is mostly captured indirectly by traditional components (HR/600 and K%, respectively). I also ran a quick robustness test to see how much contact or z-contact rate would have helped my 2025 OOPSY K% projections. They didn’t help much, e.g. going from the worst (Jose Siri) to the best (Luis Arraez) only reduced the K% projection by a fifth of a percentage point. That’s not to say the more granular metrics couldn’t help a little in a more thorough test, or that Murakami’s contact issues aren’t a concern, but I do think K% covers contact well from a projection standpoint.

Using the steeper translations based on historical data on NPB-to-MLB transitions since 2000, which assume that NPB is close to Double-A, here’s how Murakami and company would project in their first season in MLB. The translation is applied to all component statistics. All projections assume a neutral park in the 2025 MLB environment:

This projection variation happens to produce similar forecasts to ZiPS, a reassuring sign, particularly after a best-in-class 2025 season for ZiPS’ hitting projections. These OOPSY retroactive projections are also much less bullish than Steamer has been historically. OOPSY projects Murakami for a ton of strikeouts and home runs. His projection is similar to the OOPSY 2026 hitting projections for Matt Wallner and Giancarlo Stanton. Murakami projects for more walks and strikeouts than those two, but all three project for close to a 20-percentage-point gap between their strikeout and walk rates, with strikeout rates exceeding 30% and plenty of home runs. These comparables align well with Eric’s speculative peak Joey Gallo comparison.

Alternatively, if I use the more generous translation, based on MLB-to-NPB transitions that assumes that NPB is close to Triple-A, my wRC+ forecast for Murakami jumps to 135, while the retroactive wRC+ projections for the other players would be roughly as bullish as Steamer. If Murakami hits this projection, his closest 2026 OOPSY comparables would be Kyle Schwarber and Nick Kurtz, two of baseball’s best projected hitters.

If I was publishing projections six years ago, I’d likely have opted for the more generous Triple-A translation, as it is aligns more closely with conventional wisdom. With the benefit of hindsight — having seen the less bullish ZiPS projections achieve much greater accuracy than the more optimistic Steamer projections for the tiny sample of recent NPB-to-MLB players, and having seen Clay Davenport recently revise his NPB translations downward — I prefer to err on the side of caution and adopt the steeper Double-A translation for OOPSY 2026. The steeper translation has been consistent stretching back to 2000. Given the results of the delta method, using the steeper translation would have been a reasonably accurate approach for NPB-to-MLB transitions spanning the last 25 years; it also feels like the most reasonable guess moving forward. Adopting this approach assumes that the sample of future NPB-to-MLB hitters will have similar characteristics to the sample of past NPB-to-MLB hitters. If it proves too pessimistic (or optimistic!), I will have to adjust accordingly.

Part of my motivation in writing this article was to show our readers some of the difficult subjective decisions that go into producing projections. Indeed, this difficulty is part of why I decided to call my system OOPSY: I wanted to be transparent about the fact that projection systems are built upon different assumptions. In any case, the less bullish 123 wRC+ projection would still make Murakami an excellent major league hitter, well worth a contract in line with Ben’s expectations even assuming little defensive value, and a potential bargain for the White Sox. At 25, he’s entering his prime years, with a chance to make adjustments and land himself a bigger payday come 2028. As legitimately concerning as his contact rate is, his 80-grade home run power appears to be more than capable of making up for it.

So, Joey Gallo?

many of made this comp, including Longenhagen (cited in the text), and Eno, and surely others. i like the comp! Gallo obviously didn’t age well but he had a good run from 2017 to 2021 (117 wRC+ across 2,248 PA)

Gallo was, at times, a good defensive outfielder. The scouting reports on Murakami’s defence are… less positive. As in, he doesn’t compare favourably to Max Muncy at third.

for sure, it makes sense as a hitting comp only

There was never a chance he would play 3B in the majors to be fair

We don’t really know how bad he is. Rafael Devers and Max Muncy played there