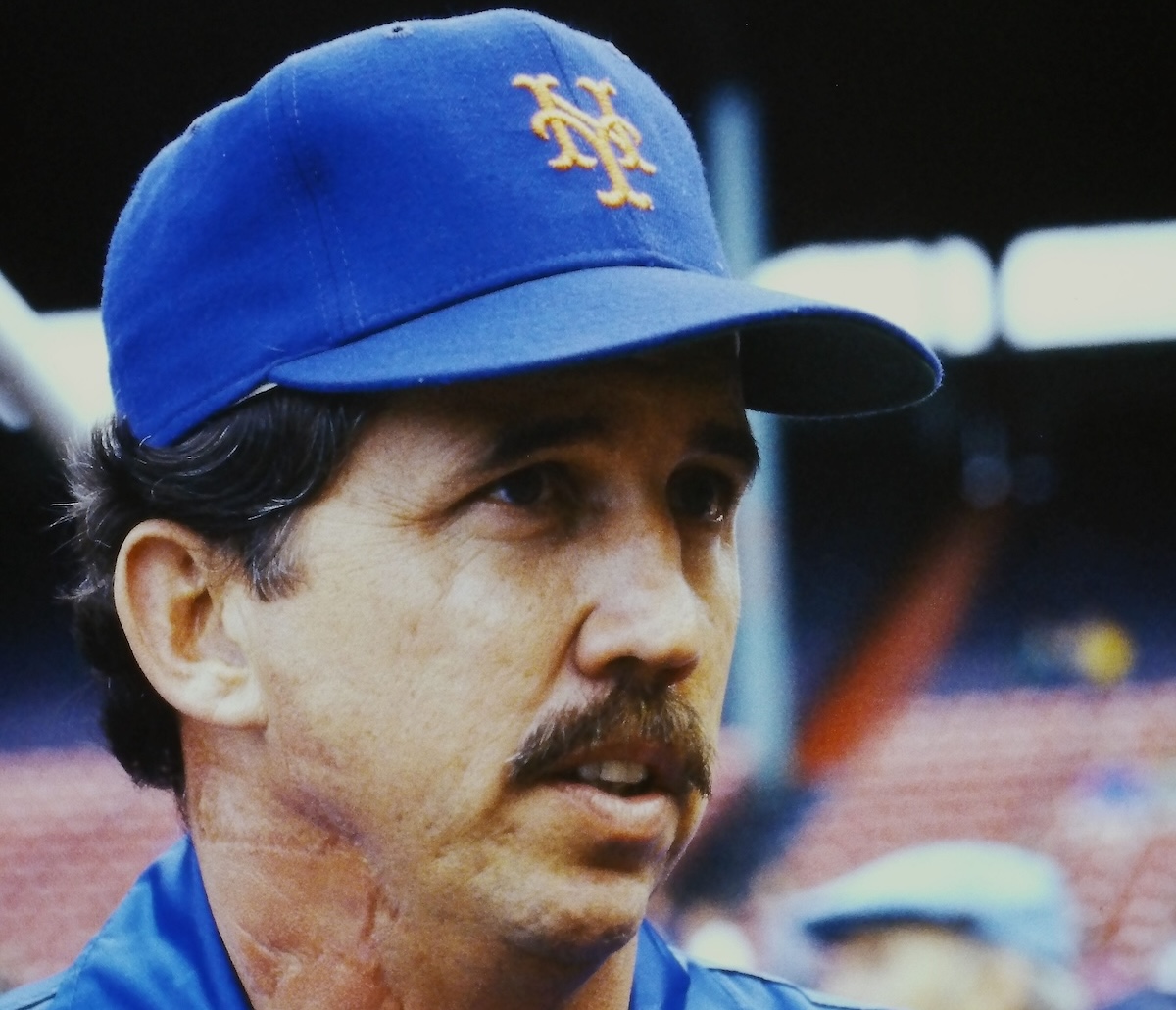

Davey Johnson (1943-2025), a Man Ahead of the Curve

As both a player and a manager, Davey Johnson was a standout and a man ahead of the curve. In a 13-season playing career that spanned from 1965 to ’78, primarily as a second baseman with the Orioles and Braves, he made four All-Star teams, won three Gold Gloves, played in three World Series, and set a home run record. In a 17-season managerial career that stretched from 1984 to 2013, covered five different teams, and included a decade-long hiatus, Johnson won six division titles, one Wild Card berth, a championship, and two Manager of the Year awards. He’s indelibly linked to the Mets, first for making the final out in their 1969 upset of the Orioles and then for piloting their ’86 juggernaut to a World Series win at the peak of a six-season run.

Johnson had a knack for turning around losing teams, and for connecting with his players. Decades before the analytical revolution took hold in baseball, he was a pioneer in the use of personal computers by managers, at a time when the machines were still a novelty. Drawing upon his offseason studies at Trinity University — from which he earned a B.S. in mathematics — and Johns Hopkins, as well as his experience playing for Earl Weaver with the Orioles, he was renowned for using statistical databases to figure out probabilities and optimize his lineup and bullpen matchups.

Johnson, who last worked in baseball as a consultant for the Nationals in 2014, died on Friday in Sarasota, Florida following a long illness. He was 82 years old.

As Johnson’s retirement from the dugout approached in 2013, the Washington Post’s Thomas Boswell, who covered the manager’s two-and-a-half-season stint with the Nationals, hailed him as “one of the smartest and most stubborn, loyal and insubordinate, independent and opinionated, honest and funny, patient and multifaceted men that baseball has ever seen.”

Johnson’s own experiences as a player no doubt helped him bridge the gap between his analytical bent and the human side of the game. “Davey is the ultimate players’ manager,” Jayson Werth told Boswell in 2013.

“I treated my players like men,” Johnson told Bob Klapisch and John Harper for The Worst Team Money Could Buy, an account of the Mets’ decline in the seasons after his mid-1990 firing. “As long as they won for me on the field, I didn’t give a flying fuck what they did otherwise.”

“He believed in his players,” Darryl Strawberry told ESPN in the wake of Johnson’s passing. Strawberry made seven straight All-Star teams (1984–90) as the Mets’ star right fielder under Johnson, but just one thereafter. “He was one of us. He believed in every last one of us… He would never throw you under the bus… We all loved him… He was the greatest manager I ever played for.”

David Allen Johnson was born on January 30, 1943 in Orlando, Florida, to parents Frederick Johnson, an Army tank commander, and Florence Johnson, a former competitive swimmer. Frederick actually left to fight in World War II before his son was born, and was captured later in 1943. While in a prisoner of war camp, his teeth were pulled without anesthesia. He escaped, making use of a hidden knife, and for awhile joined the resistance in Italy before being recaptured by the Germans and sent to a prisoner of war camp in Poland called Oflag 64.

Frederick didn’t tell his son about his harrowing World War II experiences until he was an adult. He remained in the military after the war, rising to the rank of lieutenant colonel. Young Dave was an Army brat, living on bases in Germany, Georgia and Wyoming before eventually settling in San Antonio. At Alamo Heights High School, Johnson attracted the attention of talent evaluators including Texas A&M coach Tom Chandler, who successfully recruited him.

Johnson spent two years at Texas A&M, playing on the freshman and varsity basketball (at 6-foot-1, he was a guard) and baseball teams and studying to be a veterinarian. As the Aggies’ shortstop in 1962, he hit .309 with six homers and 19 RBI as A&M went 18-7 overall, and 11-4 in the Southwest Conference. Scouted by several teams, he signed with the Orioles for a $25,000 bonus. “I signed for $25,000, which I used to buy a waterfront lot, a new car and a new set of Haig golf clubs — I was set for life at 19,” he told ESPN’s Steve Wulf in 2012.

Johnson began his professional career in 1962, as a 19-year-old shortstop with the Orioles Class-C affiliate in Stockton, California, where he hit .309/.387/.519 with 10 homers in 97 games. He spent half of the 1963 season playing under Weaver at Double-A Elmira before moving up to Triple-A Rochester, where he was teammates with pitcher Pat Gillick, who in 1995 would join the Orioles as general manager in part because they had hired Johnson to manage.

Johnson spent all of 1964 at Rochester, hitting .264/.345/.458 with 19 homers while splitting time at the two middle infield positions because the Orioles had All-Star and future Hall of Famer Luis Aparicio at shortstop. Johnson made the Orioles out of spring training in 1965, but played in just 19 games, going 8-for-47 during the season’s first two months while backing up Aparicio, second baseman Jerry Adair, and third baseman Brooks Robinson, another future Hall of Famer.

In June 1965, the Orioles sent the 22-year-old Johnson back to Rochester, but he won the Orioles’ starting job at second base the next spring, displacing Adair, who was soon traded. He hit a modest .257/.298/.351 (87 OPS+) with eight homers, and finished tied for third in the AL Rookie of the Year voting. Fueled by the arrival of AL Triple Crown winner (and MVP) Frank Robinson, the Orioles won their first pennant, then swept the defending champion Dodgers in the World Series. Johnson went 4-for-14 with a double against the Dodgers; the first of his two hits in Game 2, a single off Sandy Koufax, proved to be the last hit the future Hall of Famer surrendered before retiring in November of that year.

Settling into the second base job, Johnson hit a combined .263/.337/.380 (106 OPS+) with an average of nine homers and 3.0 WAR over the next four seasons (1967–70). He had a 107 OPS+ in three of those (all but 1968) and made three straight AL All-Star teams from 1968–70; for the last of those, he started in place of the injured Rod Carew.

Off the field, Johnson continued his education, studying mathematics first at Trinity University in San Antonio and then at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore. While at Hopkins, he came across Earnshaw Cook’s 1964 proto-sabermetric tome Percentage Baseball, which stressed the importance of on-base percentage. Johnson struck up a friendship with Cook, a Princeton-trained engineer teaching at Hopkins. During the 1968–69 offseason, Johnson persuaded Orioles owner Jerry Hoffberger to let him use the IBM mainframe of the National Brewery (of which Hoffberger was chairman) to test his theories about baseball. Inputting the batting statistics of the Orioles via punch cards, he created a presentation — “Optimization of the Baltimore Orioles Lineup” — in which he argued he should bat second instead of sixth or seventh, which would help the Orioles score “50 or 60 more runs” by Johnson’s estimate. According to Newsday’s Steve Jacobson, “In the process, Johnson blew out the memory for Colt .45 [a National Brewery beer property] in three territories.” The paper wound up in the irascible Weaver’s trash can, “But I know he got it out of there after I left,” Johnson told ESPN’s Jerry Crasnick in 2011. Johnson would absorb plenty from the statistically inclined skipper, including his disdain for bunting in favor of swinging for the fences.

Johnson was brazen enough to offer unsolicited advice to even the best Orioles pitchers, such as perennial 20-game winners Jim Palmer and Dave McNally. From a 2012 Tyler Kepner story in the New York Times:

“You’re in an unfavorable chance deviation,” Johnson would tell them, to puzzled annoyance. “You’re trying to throw for the corners, and you’re missing a foot away or you’re missing right down the middle. So I suggest, when you’re in an unfavorable chance deviation, throw it down the middle and you’ll hit the corners.”

After that, Johnson said, the pitchers called him Dumb-Dumb.

In 1969, Johnson began a string of three straight Gold Glove seasons and the Orioles emerged as a powerhouse under Weaver, who had taken over from fired manager Hank Bauer in mid-’68. The 1969 Orioles won 109 games, then swept the Twins in the inaugural best-of-five American League Championship Series before being upset by the 100-win Miracle Mets in the World Series. Johnson went just 1-for-16 against the Mets, and made the final out against Jerry Koosman, hitting a warning-track fly ball to left fielder Cleon Jones. On contact, Johnson believed he had hit a game-tying two-run homer. “A big gust of wind must have come along at that very moment and blown the ball back in,” he wrote in his 2018 memoir, Davey Johnson: My Wild Ride in Baseball and Beyond.

The Orioles won 108 games in 1970, and again swept the Twins in the ALCS, during which Johnson homered off Luis Tiant and Jim Perry. After collecting just two hits in the first four games of the World Series against the Reds, he went 3-for-4 with a double and two RBI in the Game 5 clincher. In 1971, he had his best season to date, hitting .282/.351/.443 (125 OPS+) with 18 homers and 4.4 WAR. Despite hitting 16 of his 18 homers before the All-Star break, he missed the All-Star team but won his final Gold Glove while helping Baltimore to another pennant; he did suffer a second-half power outage, linked to separating his left shoulder in a collision with a catcher. He went just 4-for-27 in the Orioles’ seven-game loss to the Pirates in the World Series, though his game-tying RBI single off Dave Giusti in the seventh inning of Game 6 did help push the Series to go the distance.

Things fell apart for Johnson in Baltimore in 1972, as his left shoulder became a problem. “Weaver kept sending me to the hospital, and nobody diagnosed it until I was traded to the Atlanta Braves,” Johnson told Metzmerized Online in 2018. “They diagnosed it as a subluxed shoulder from running over catchers, and it stretched all the muscles in my left shoulder. I couldn’t pull through with my left hand; it would collapse.” Due to his shoulder woes and the emergence of Bobby Grich — a fielding whiz who in his first full major league season made the AL All-Star team while splitting time at shortstop and second base — Johnson played in just 118 games and hit just .221/.320/.335 (93 OPS+) with five homers. The Orioles dropped from a 101-57 record in 1971 to 80-74 in ’72 (a players strike shortened the season). On November 30, Johnson and three other players, including former 20-game winner Pat Dobson and future manager Johnny Oates, were sent to the Braves in exchange for catcher Earl Williams and a prospect.

Johnson, who was about to turn 30, was happy with the trade, which put him in hitter-friendly Atlanta Fulton County Stadium, which had the majors’ highest elevation at the time, 1,050 feet above sea level, and was known as “The Launching Pad.” Batting behind Henry Aaron — whom he credited with helping him become a better hitter — Johnson hit .270/.370/.546 (143 OPS+), setting new highs in all but batting average. Abandoning the inside-out approach that had been instilled in him since his days in Triple-A, he bashed a career-high 43 homers, 42 of which were as a second baseman, tying Rogers Hornsby‘s record (in the strict split); his additional homer as a pinch-hitter gave him the most homers by a player whose primary position was second base (à la Salvador Perez at catcher, at least until Cal Raleigh showed up). Those 43 homers were more than the combined total of the next two second basemen (Joe Morgan‘s 26 and Pedro Garcia’s 15). With Aaron clubbing 40 homers and third baseman Darrell Evans 41, Johnson was part of the first trio of teammates to reach 40 in a season. It wasn’t enough to help the Braves finish above .500, though; they went 76-85.

Johnson receded to a 107 OPS+ and 15 homers in 1974, a season highlighted by Aaron’s 715th home run. He split time between second and first base; his 30 errors the season before and the shift of shortstop Marty Perez to second factored into the move. Unhappy with the prospect of becoming a platoon first baseman, he played just one game with the Braves in 1975 before being released and signing with the Yomiuri Giants, whose star slugger, Sadaharu Oh, would hit his 715th homer that season. It was a miserable campaign for Johnson, who hit just .197/.275/.356 with 13 homers and was nicknamed Dame (No-Good). He broke a bone in his shoulder, lost 20 pounds due to stress, and struggled to play third base, where he was replacing Hall of Famer Shigeo Nagashima, who had retired to manage the team. Johnson rebounded in 1976, returning to second base, winning a Gold Glove and a spot on the Best Nine (an end-of-season All-Star team) while helping the Giants to the Japan Series.

Clashes with Nagashima, Giants executives, and Japanese baseball culture in general — including one over his decision to return to the U.S. for treatment of a neuroma in his left thumb — led Johnson to leave Japan after two seasons. He signed with the Phillies, and had an excellent season as a reserve, hitting .321/.408/.545 (149 OPS+) in 186 plate appearances for a team that won the NL East. Aside from becoming the first player to pinch-hit two grand slams in a season in 1978, he couldn’t replicate the magic the next season, during which he was traded to the Cubs. A pair of ruptured discs in his back, the result of more collisions with catchers, caused him unbearable pain that led to surgery.

In 1979, as his career was winding down, the 36-year-old Johnson got his first taste of managing the independent Miami Amigos in the short-lived Inter-American League, which also had franchises in Venezuela, the Dominican Republic, Panama, and Puerto Rico. The league folded midseason, but Johnson was just getting started as a skipper. The Mets hired him to pilot their Double-A Jackson affiliate in 1981, at which point he said he had no aspirations to manage in the majors “because I’m not too good at taking orders from an owner or general manager about how things should be run on the field.” He added, “I think where I will excel is helping young players understand themselves.”

The Jackson team went a respectable 68-66. After spending the 1982 season serving as a scout and minor league hitting instructor, Johnson took over the Mets’ Triple-A Tidewater affiliate in ’83. At the latter stop, he managed Strawberry, Ron Darling, and several other players he would later oversee in New York. He also introduced the use of a computer to minor league baseball, and took that with him to the majors the following year, when general manager Frank Cashen — who had served as the executive vice president and general manager of the Orioles during Johnson’s tenure in Baltimore — hired him.

The Mets had gone 68-94 under George Bamberger (who was fired on June 2) and interim manager Frank Howard in 1983, though Strawberry earned NL Rookie of the Year honors and Keith Hernandez arrived in mid-June after a trade with the Cardinals. Still, the team hadn’t finished above .500 since 1976, Tom Seaver’s last full season before being traded to the Reds; there was nowhere to go but up. At his introductory press conference, Johnson gave reporters a taste of his unvarnished style when he spoke of Howard agreeing to return to coaching on his staff by saying, “Frank is a stubborn man, he won’t hide his opinion from you. To be honest, I didn’t like the way he managed. But he’s a good baseball man.”

Johnson was decades ahead of his time in using statistical databases to figure out probabilities and optimize his lineup, though thanks to his experience as a player, he avoided much of the stigma that would later surface against the so-called Moneyball backlash. “Players aren’t machines,” he told the Boston Globe’s Lesley Visser in 1985, “but the chances of something happening in a particular situation are illustrated by the computer. I don’t run my club by computer, but I use it as another tool.”

Johnson’s players didn’t necessarily love knowing that their boss was using a computer, but fortunately, the Mets were amassing talent. The colorful, star-studded squad won 90 or more games annually from 1984–88, capturing division titles in ’86 and ’88 and never finishing below second in the NL East.

The Mets won 90 games in Johnson’ first season — their highest total since 1969 — fueled by the arrival of 19-year-old phenom Dwight Gooden. After striking out 300 batters in 191 innings at A-level Lynchburg, Gooden had such a strong spring that Johnson lobbied Cashen to take him north despite his inexperience. He ended up winning NL Rookie of the Year honors while going 17-9 with 276 strikeouts and a 2.60 ERA. With the 23-year-old Darling and 21-year-old Sid Fernandez (both of whom debuted the year before, the latter with the Dodgers) joining Gooden in the rotation, a youth movement was underway.

With Cashen trading for perennial All-Star catcher Gary Carter, the farm system producing center fielder Lenny Dykstra, and Gooden winning the NL Cy Young with a season for the ages (24-4, 1.53 ERA, 268 strikeouts), the Mets went 98-64 in 1985, finishing second in the NL East by three games. When the team reported to spring training the next year, Johnson told them, “I don’t have a whole lot to say. We’re going to win it all, and we’re going to dominate.”

“And [the players] looked around at each other and said, ‘You know what? He’s right. We’re going to dominate,'” recalled Strawberry. He was right. During the regular season, the Mets went 108-54, the best record of any team during the 1976–97 span. The team claimed a share of first place on April 22 and never left; by July 1, the Mets were 51-21, with a 10 1/2-game lead in the NL East, which they wound up winning by 21 1/2 games. Gooden regressed, but by this time the team had a top-notch rotation that also featured righties Darling and Rick Aguilera and lefties Fernandez and Bob Ojeda.

Still, nobody rolled over for the powerhouse Mets in the postseason. They had to outlast the 96-win Astros in a six-game NLCS whose last two games — both New York victories — went 12 and 16 innings. Then they overcame a three-games-to-two deficit to win the World Series over the Red Sox. First they rallied from down 5-3 in the 10th inning of Game 6, aided by wild Red Sox relievers and first baseman Bill Buckner‘s costly error on Mookie Wilson’s groundball, which allowed the winning run to score. Then they rallied back from a 3-0 deficit in the sixth inning of Game 7, ultimately winning 8-5.

The Mets slipped to 92 wins in 1987, finishing three games behind the Cardinals, but rebounded to win 100 games and the NL East in ’88. That team met an ignominious fate, however, losing a seven-game NLCS to the Orel Hershiser-led Dodgers after going 10-1 against them during the regular season. After the team slipped to 87 wins (and another second-place finish) in 1989 while Carter and Hernandez suddenly started showing their age, ongoing clashes with the Mets’ front office made a 20-22 start in 1990 too much to survive. Johnson learned of his dismissal via a television report.

Still under contract with the Mets, Johnson spent the next three years tending to his eclectic non-baseball interests, including not just golf and fishing but also flying (he was a licensed pilot), scuba (he was a licensed instructor), and real estate (he had a license and grew wealthy buying apartments in Orlando before the Disney empire increased the property value). He didn’t get another managerial job until mid-1993, when he took over the Reds, for whom he had been serving as a consultant after interviewing to succeed Lou Piniella, who had resigned after going 90-72 in 1992. Tony Perez, whom 31-year-old general manager Jim Bowden hired instead of Johnson, lasted just 44 games before getting canned. Managing the likes of future Hall of Famer Barry Larkin, Reggie Sanders, Bret Boone, and Jose Rijo, Johnson guided the Reds to first place finishes in both 1994 (66-48 in the strike-shortened season) and ’95 (85-59 in the lockout-shortened season). The strike wiped out the 1994 postseason, but the following year, the Reds swept the Dodgers in the Division Series before being swept by the Braves in the NLCS.

Johnson didn’t get along with owner Marge Schott, who was under suspension for “use of racially and ethnically insensitive language,” though she retained control of the team as general partner. Schott disapproved of Johnson living with his fiancée before marriage, and announced in mid-1995 that he would not return as manager.

Johnson returned to Baltimore, where he took over a team that featured future Hall of Famers Cal Ripken Jr. and Mike Mussina as well as Rafael Palmeiro. He ran into Gillick — who had rebuffed owner Peter Angelos’ overtures to interview for the vacant GM job after Roland Hemond’s resignation — at the GM meetings in November 1995. “It was Davey’s energy that got me [interested],” said Gillick upon being hired.

Gillick soon signed another future Hall of Famer, Roberto Alomar, and in mid-1996 he would add yet another in Eddie Murray. Spurred in part by Brady Anderson’s 50-homer breakout — a fluke season that stands out in his career context not unlike that of Johnson’s 1973 — the Orioles won 88 games and the AL Wild Card in 1996, then beat Cleveland in the Division Series before falling to the Yankees in the ALCS. The next year, with Harold Baines, Eric Davis, and Jimmy Key all arriving, the team won 98 games but again could get only so far as the ALCS. Another clash with an owner (Angelos) led Johnson to fax in his resignation on the same day he was named the 1997 AL Manager of the Year. It would take 15 years for the Orioles to field another team that finished above .500.

Johnson next surfaced in Los Angeles, where he spent two undistinguished years at the helm of the Dodgers (1999-2000), a franchise in the midst of a jarring transition from the stability of the O’Malley family ownership and managers Walter Alston and Tommy Lasorda to ownership by News Corp. and a revolving door in the manager’s office. Johnson didn’t get along with general manager Kevin Malone, who was openly critical of the manager. Despite having stars such as Gary Sheffield, Kevin Brown, Chan Ho Park on a team with the majors’ third-highest payroll, the Dodgers won just 86 games, and by the end of the season, it appeared likely Johnson would be fired. When he was ejected in the second inning of the season’s final game in 2000 — which the Los Angeles Times assumed would be his last with the Dodgers — he was convinced he’d never manage again.

Johnson spent over a decade away from the majors, dealing with burnout, health problems, and personal tragedy. He ruptured his appendix in 2004, a problem that took several months to diagnose and required five surgeries to fix. In 2005, he lost his 32-year-old daughter, world class surfer Andrea Lyn Johnson, to a degenerative tissue disease related to medications she taking for schizophrenia. In 2010, his 34-year-old stepson, Jake Allen, who was blind and deaf, died of pneumonia. In 2011, he was treated for atrial fibrillation, which sapped his strength. Even during those trying times, he kept a toe in the game by dabbling in international baseball, first with the Netherlands national team as a fill-in manager in 2003 and a bench coach for the 2004 Summer Olympics team. He served as the bench coach of Team USA in the 2006 World Baseball Classic under Buck Martinez, then managed the team at the 2008 Summer Olympics (where they won a bronze medal) and 2009 World Baseball Classic (where they finished fourth).

In June 2006, Bowden, by then the Nationals’ vice president/general manger, hired Johnson to serve as a consultant. After Bowden resigned amid a scandal involving the skimming of signing bonus money in 2009, successor Mike Rizzo promoted him to senior consultant. On June 26, 2011, the 68-year-old Johnson took over the job of managing the Nationals after the unexpected resignation of manager Jim Riggleman. In his first full season back, he navigated a squad featuring 19-year-old Rookie of the Year Bryce Harper and pitching phenom Stephen Strasburg (who was controversially shut down in mid-September) to an NL-best 98 wins and a division title — an accomplishment that helped him win his second Manager of the Year award.

“Every single day you come into this clubhouse, he’s smiling, laughing, joking around,” Harper told Kepner. “He’s young at heart. We love having him around.”

Alas, the Nationals squandered a two-run lead in the ninth inning of the fifth and deciding game of the Division Series against the Cardinals. Closer Drew Storen, pitching for the third straight day, was one strike away from sealing the series when all hell broke loose — walk, walk, two-run single, steal, two-run single — as Johnson watched. While the Nationals won 86 games in 2013, they missed the postseason. The 70-year-old Johnson was nudged back into consulting, a role in which he spent one more season.

Johnson came up for consideration on Hall of Fame Era Committee ballots twice in recent years. On both the 2019 Today’s Game ballot and 2024 Contemporary Baseball Managers/Executives/Umpires ballot, he got so little support that he was lumped in with other candidates who received five or fewer votes; meanwhile, Baines and Lee Smith were elected on the 2019 ballot, and Jim Leyland on the 2024 one.

Johnson’s main obstacle in that context is a short career compared to others who have been enshrined purely as managers. Among those from the 20th and 21st century, only Whitey Herzog and Billy Southworth managed fewer games than Johnson’s 2,443, but both won at least three pennants, where Johnson only won one. Johnson’s 1,372 wins ranks a modest 33rd all time, but on the other hand, his .562 winning percentage is 15th among those who managed at least 1,000 games, eighth if you limit the field to those who did so after the 19th century behind the active Dave Roberts (.619) and Hall of Famers Joe McCarthy (.615), Southworth (.597), Frank Chance (.593), Al Lopez (.584), Weaver (.583), and Aaron Boone (.581). Even including 19th-century managers, Johnson is 17th in games above .500 (301), joining the 16th-ranked Dusty Baker and the 11th-ranked Roberts as the only ones among the top 21 who aren’t enshrined either as managers, pioneers/executives, or players.

Johnson’s short stops after managing the Mets, his postseason track record, and his confrontations with management may be impediments as well — baseball executives make up part of the voting committees, after all. Johnson never lasted even three full seasons in any other job, not that it was always his fault; Schott was a pariah, Angelos let the Orioles lapse into a decade and a half of irrelevance, and Malone never worked in baseball again after resigning from the Dodgers. More damningly, four times — in 1986 and ’88 with the Mets, in ’97 with the Orioles, and 2012 with the Nationals — Johnson led a team with the league’s best record into the postseason, yet only once did he make it through to the World Series. For as innovative as he may have been in the dugout, he would be the only post-19th century manager enshrined without having won at least two pennants. On the 2024 ballot, he was up against three other managers, two of whom (Leyland and Cito Gaston) won multiple pennants. The third, Piniella, won the only World Series in which he managed, like Johnson. Despite lower rankings and lesser totals along the lines of those above, Piniella missed election by just one vote, while Leyland was elected.

With all due respect to his competition on that ballot, for as successful and colorful as those managers were, none was the innovator that Johnson was. He was a man ahead of his time, and he left a huge mark on the game.

Brooklyn-based Jay Jaffe is a senior writer for FanGraphs, the author of The Cooperstown Casebook (Thomas Dunne Books, 2017) and the creator of the JAWS (Jaffe WAR Score) metric for Hall of Fame analysis. He founded the Futility Infielder website (2001), was a columnist for Baseball Prospectus (2005-2012) and a contributing writer for Sports Illustrated (2012-2018). He has been a recurring guest on MLB Network and a member of the BBWAA since 2011, and a Hall of Fame voter since 2021. Follow him on BlueSky @jayjaffe.bsky.social.

While I love Bobby V I feel comfortable in saying that Davey was the best Mets manager in my lifetime. He should be in the hof and would have waltzed in if not for being upset by the Dodgers in the heartbreaking series in 88. I cried my eyes out as an eight year old when they lost that series. Davey should have pulled Gooden after he got in trouble in the ninth of game four(the game that swung the series), and brought in Myers, who was dominant that season but that was really my lone complaint. Davey won almost everywhere but he had some awful owners in Schott(who was the worst of the worst), and Angelos who ran him off after two great seasons. He might have won it all in 2012 if Strasburg wasn’t shut down. I believe the only player that really hated Davey was Lenny Dykstra and let’s be honest he’s Lenny Dykstra who is a scumbag. Yeah, Davey and Darryl at times had a rocky relationship but Darryl had monster years under him. It is funny how the three most successful Mets managers in my lifetime all didn’t get along with their gm in Bobby V, Davey and Terry Collins. Anyway my condolences to the Johnson family as Davey was a legend and way ahead of his time as Jay said. There are many great remembrances of Davey written in the last 48 hours and imo this one’s the best.

Hindsight’s 20/20 and he wasn’t an outlier or anything when it came to pitcher use but I think there are a lot of times it may have benefitted Gooden and the Mets if Davey had pulled him earlier.

Again, I don’t blame Johnson for this at all, but one of those things I’ve long believed is that Gooden and Valenzuela would’ve had much different careers if they hadn’t been used so much so early.

Of course. We can point to just about any young phenom who burned bright and fast knowing what we know now. On the other hand, what those pitchers accomplished in a shorter period made them more memorable.

Speaking about Game 4, and within the standards of the time, Johnson would have been vilified if he took Gooden out in the 9th. Up two, only allowing four baserunners from innings 2-8? No way is he coming out.