Daylen Lile, Washington’s Silver Lining

The Nationals will remember 2025 as a gap year, if they’re lucky. The 2023 and 2024 teams, invigorated by many of the prospects acquired in the Juan Soto trade, each won 71 games, dragging Washington out of the bottom-of-table ignominy that it had occupied since winning the World Series in 2019 and then blowing up the roster. This year’s squad is going to finish with a win total in the 60s and some developmental hiccups, a step backward from the recent past. But lost in the broadly disappointing year is one bright shining beacon: Daylen Lile might just be a keeper.

Lile, a high school draftee in 2021, missed all of 2022 rehabbing from Tommy John surgery, then spent the next two years methodically climbing through the minor league ranks. He started 2025 hot, with a .337/.383/.509 line in his first 40 games in the minors, and got his first taste of the majors when Jacob Young briefly hit the IL. Lile struggled during that first stint but landed in the majors for good a few weeks later when the Nats overhauled their bench. By the All-Star break, he’d carved out a role as a rotational right fielder.

That’s the boring part of this article. The exciting part? As Lile settled into big league life, opportunity beckoned. Young scuffled. Alex Call got traded. Dylan Crews was still out with injury. Lile? He just kept hitting. By August, he was locked in as a starter, and why not? Since the break, he’s hitting a sensational .323/.371/.552 for a 153 wRC+, and turning heads with his aggressive approach and hair-on-fire baserunning. Move over, other baby Nats – there’s a new top youngster in town.

Lile’s game is built around a sensational feel to hit. He regularly ran gaudy contact rates in the minor leagues, and his zone contact rate in the majors is above 90%, squarely in the upper echelon of the league. Like many hitters who make a ton of contact, Lile likes to swing. Unlike those peers, though, he’s done a good job of avoiding the over-chase downward spiral that traps so many singles hitters into lunging at sliders off the plate.

A lot of articles I write about young hitters focus on whether they’ll be able to stop swinging at so many bad pitches. Here, though, I don’t have a lot to say on Lile’s plate discipline. If he can keep it up, why mess with it? I’m more interested in what happens after he makes contact with the ball, and that’s been an absolute revelation so far this year.

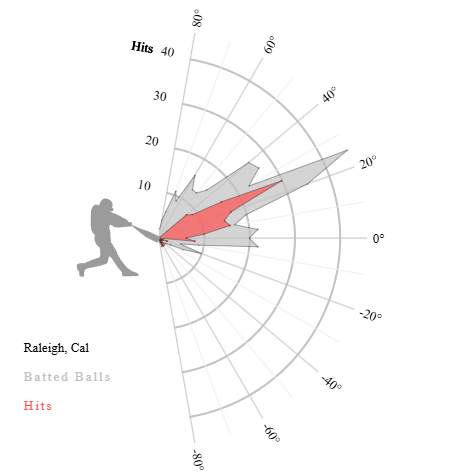

Have you seen these little Statcast plots that show how often players hit the ball at different launch angles? Here’s Cal Raleigh, for example, trying to hit everything in the air and mostly succeeding:

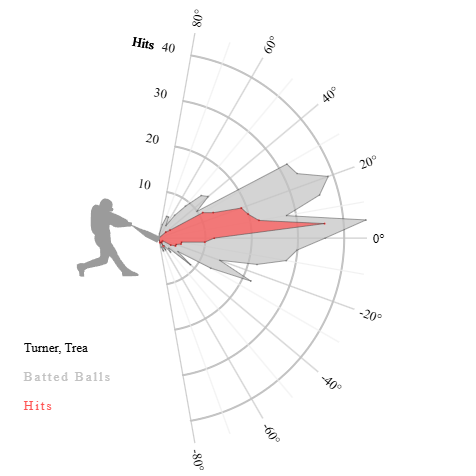

Trea Turner demonstrates another popular shape, hitting plenty of lofted balls for power and then a ton of well-struck grounders that take advantage of his speed:

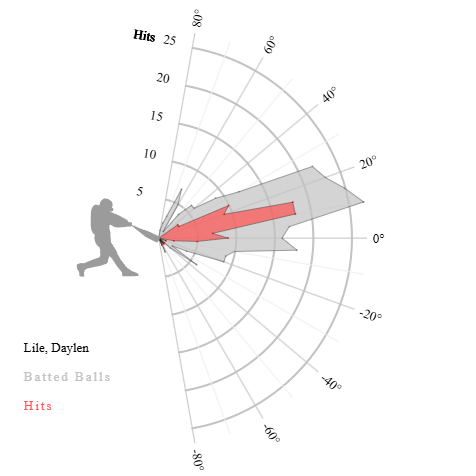

Lile’s chart is a lot more exciting to me. He doesn’t have the power to imitate Raleigh, but he’s not limiting himself to grounders. Instead, he’s just trying to hit line drives:

They say that line drive rate is noisy. They’re not wrong – but they’re not entirely right, either. Batters exert a decent amount of control over line drive rate; it might be noisy in general, but some hitters really are better at hitting line drives. That feels like it should be obvious, but it’s worth pointing out anyway because I find that, “Oh, so you assume everything is random,” is a criticism that frequently gets leveled at sabermetric analysis even when it’s not really the case. Will Lile keep hitting line drives at a rate that matches the career marks of Luis Arraez and Freddie Freeman? Probably not. But will he keep hitting meaningfully more line drives than average? I’d bet on it.

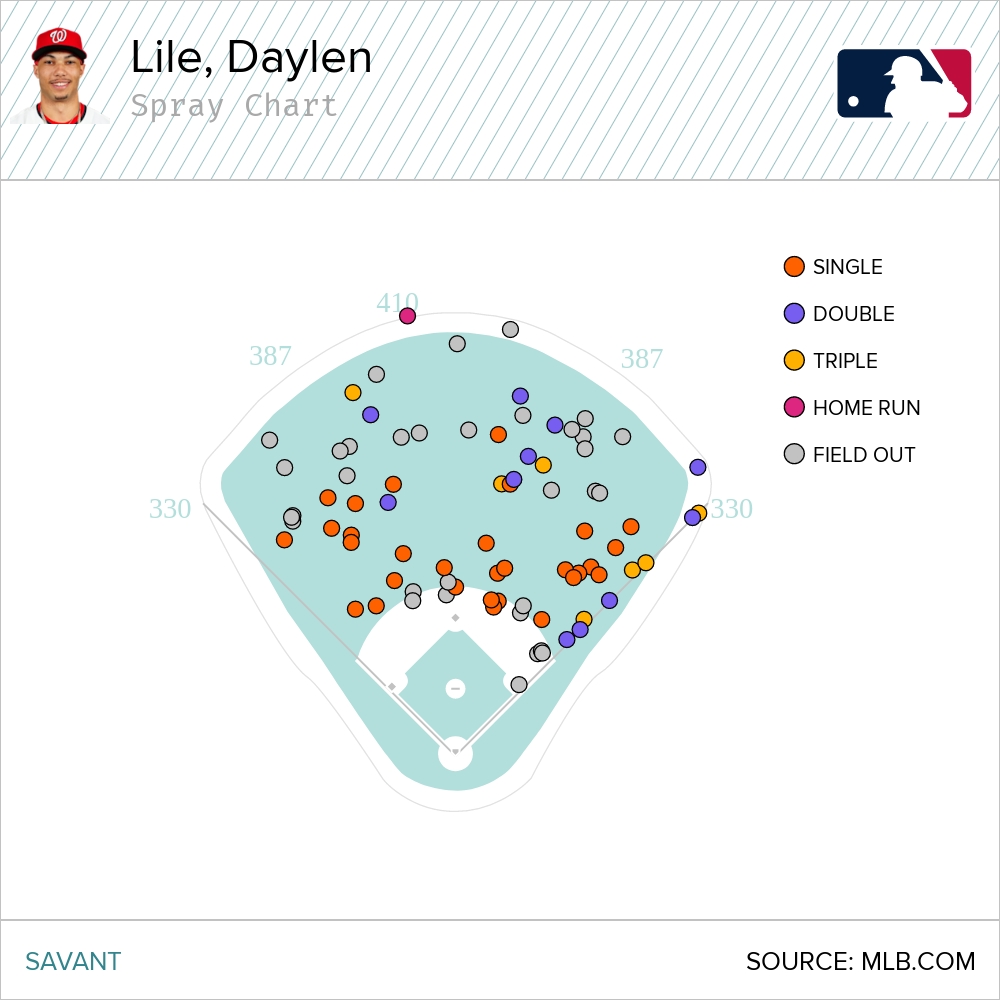

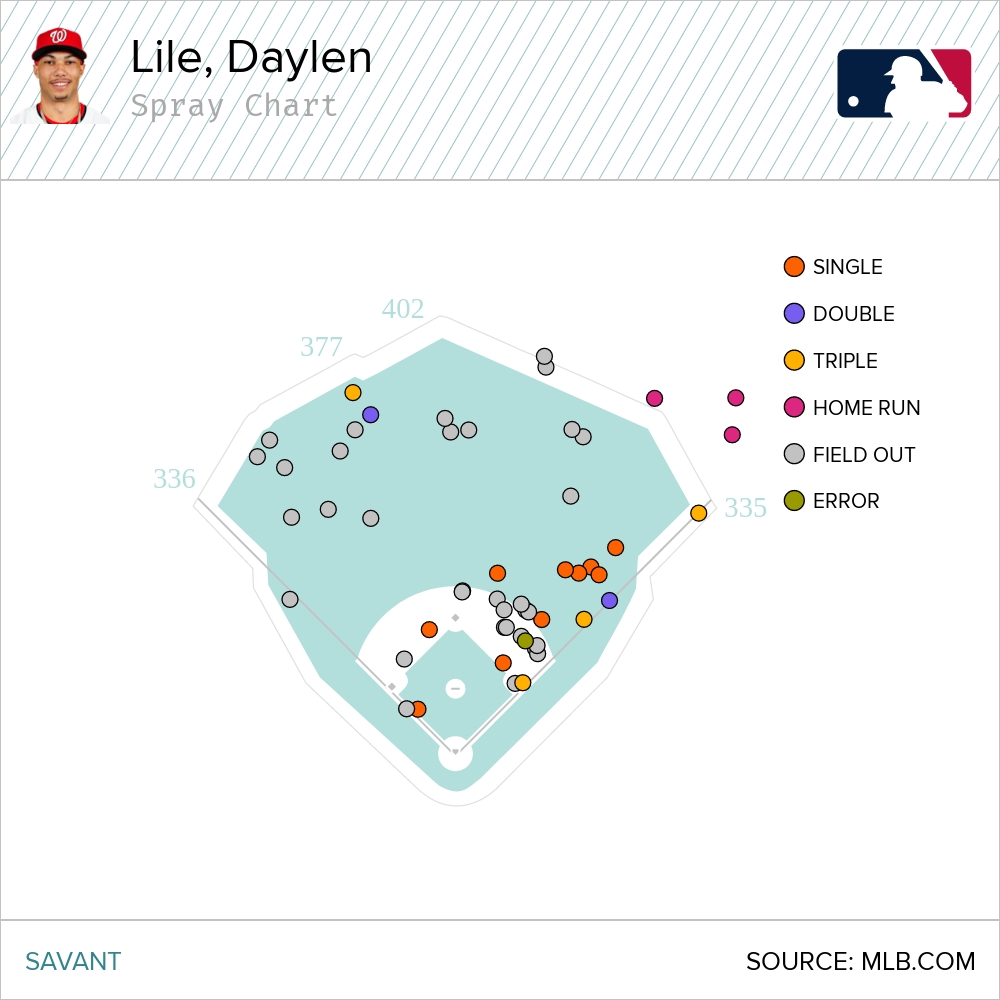

The laser-beam show Lile is putting on every night showers all fields equally. His line drive spray chart has its fair share of down-the-line shots, but it’s evenly distributed overall:

To me, that show’s Lile’s intent quite plainly. He’s adept at moving his bat around the zone to make square contact, and that means prioritizing catching the ball square over controlling which way it goes. Those line drives might not produce a ton of home runs, but they’re incredibly effective nonetheless; Lile is batting .598 with a .651 wOBA on his line drives, and that’s right in line with what Statcast’s expected metrics say. That’s pretty much par for the course for line drives, which is great when you’re hitting so many of them. The guys you associate with this spray-hitting behavior – the Arraezes and Steven Kwans of the world, in other words – mostly hit for below-average damage on their line drives, because they’re slowing their swing down a ton to make square contact.

Another way of putting that last part into context: Lile has a 46% hard-hit rate on his line drives. That’s roughly double the rates that Kwan and Arraez have produced this year, and not far shy of Freeman, perhaps the best line drive hitter on the planet. Lile doesn’t have the same top-end power as Freeman, but his combination of frequent and well-struck line drives is similar. The top of the line drive rate list is split roughly evenly between pure contact types and power hitters who hit line drives. Lile’s contact quality is somehow closer to the second group even while his speed and size make you think he’s a member of the first.

Another hugely positive sign in the early going: When Lile wants to power up, he can. On his hardest swings, the ones that are at least three miles an hour faster than his average, he goes from a 35% pull rate (all other swings) to a 50% mark. He hits fewer grounders on those swings, to boot. In other words, on the swings that benefit the most from lifting and pulling, he lifts and pulls. The rest of the time, he lets his bat-to-ball skills do the work. If you’re not planning on clobbering the ball, a soft liner anywhere will do. If you get your best swing off, though, you should be aiming for extra bases to the pull side, and that’s exactly what Lile has done. Here’s the spray chart of what happens to the ball when he swings hard and connects, featuring half of his home runs:

This combination of sprayed line drives plus sporadic power is no accident. Lile told David Laurila that he wants to hit the ball from foul pole to foul pole with a “quick, straight-to-the-ball, line drive approach.” Yep, check. He said he’s already naturally equipped to drive the ball in the air: “There’s nothing mechanically that I need to try to do to drive the ball in the air. It’s more timing-based.” Again, that matches his swing data. When he’s on time, he meets pitches out in front with faster swings and pulls the ball. It’s a lot easier to extrapolate an approach from batted ball data when a player says exactly what he’s trying to do, and Lile’s stated intent matches what he’s done in the big leagues almost perfectly.

The strangest thing about Lile’s season? He’s improved in pretty much every under-the-hood statistic relative to his minor league numbers. He’s chasing less often in the big leagues while swinging at strikes more often. He’s never run a lower swinging strike rate, even in a partial season. His strikeout rate is actually lower in the bigs than it was in 2024, when he was splitting time between High-A and Double-A. That kind of improvement is always worth a little skepticism, and it’s a good bet that Lile’s plate discipline will come back to his career norms by at least a hair. But he can afford it, because the approach he’s taking right now gives him a lot of room to succeed.

In fact, the biggest problem with Lile’s debut season has been his defense. It sounds weird. Lile is an electric baserunner. He already has 11 triples and an inside-the-park home run in half a season. His sprint speed is in the 93rd percentile league-wide. He’s also one of the worst outfield defenders in the sport, as both Statcast and Sports Info Solutions agree.

I’ve watched a lot of Lile’s outfield play trying to diagnose the issue. My best guess? He just doesn’t have enough experience. Because of his elbow surgery, Lile simply hasn’t gotten a lot of reps out there. In 2023, he logged around 800 outfield innings. In 2024, he managed roughly 1,000 more. But that means the 600 innings he’s played in Washington this year represent a meaningful proportion of his total professional experience.

One consistent flaw in Lile’s defense: He’s been slow to make his initial read and get moving. I saw this on several plays that Statcast deemed he should’ve made, and yet Lile couldn’t prevent the ball from falling for a hit. His first step is at times tentative or flat when it needs to be decisive. His burst and reaction metrics are below average as a result. To make matters worse, teams are running on him quite frequently, and he hasn’t made them pay for it with a pile of outfield assists. The result is a guy who looks like he should be a great defender when he’s at full stride – and yet, he’s been pretty poor by every conceivable way of measuring it. This feels like something that will improve quickly with more time in the majors, but it’s absolutely something worth keeping an eye on.

Lile could probably use a bit of seasoning in his basestealing, too. He’s been caught six times already while only stealing eight bags, a miserable ratio. That’s despite his overall excellent baserunning; he’s been three runs above average in all non-steal baserunning situations and 1.5 runs below average stealing. That’s another case where more reps will be helpful. Before this year, Lile had basically been stealing with impunity against defenders who had no shot to throw him out. He had an 81% success rate in the minors. In a lost season, the Nats have every reason to let him run and figure out his own boundaries.

That’s kind of the story of Lile right now. His overall statistics aren’t mind-blowing. Roughly one win in half a season? Ho hum. A 125 wRC+? Eh, we’ve seen better. A bad defender who can’t even crack double digits in home runs? Yawn. But I’d argue that the real picture is much different than that.

Lile’s chief skill, the ability to put bat to ball at great frequency while still lifting and pulling when he gets a pitch to drive, is one of the most valuable skills in all of baseball. It can’t be taught, and even many of the people who have it don’t use it to its fullest extent. Lile’s approach at the plate is sophisticated beyond his years, and the fact that he makes so much contact means that there’s no silver bullet way to counter him. He’s above average against fastballs, breaking balls, and offspeed pitches. He hits high velocity just fine. His strikeout rate isn’t low because pitchers are still figuring out a plan of attack; it’s low because he puts the ball in play a lot and doesn’t chase too much.

The rest of the stuff around his game? The bad routes in right field, the times caught stealing? Those are a lot easier to change. The odds that Lile is as bad defensively in 2026 as he is in 2025 are virtually zero. The odds that he doesn’t get a little better at picking his spots to steal are likewise tiny. These are skills of experience, skills that everyone gets better at with more seasoning, and Lile just hasn’t had enough of that, by quirk of draft year and injury history.

So ignore WAR, at least in this one instance. It’s misleading you. Daylen Lile is one of the most intriguing debuts of the 2025 season, with a throwback skill set that nonetheless works well in the modern game. His warts might cost him plenty of value in the present day, but that value is ephemeral. Next year, Lile could be basically the same player he is this year, and yet post a much better overall line. It would almost be surprising if he doesn’t, in fact. Hitters this pure don’t come around all that often, and I’m wildly impressed by how Lile has lived the line drive lifestyle without falling into the various traps that stop other hitters from making it in the big leagues by leaning primarily on their bat-to-ball skills.

Ben is a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @benclemens.

I initially wondered why he’d be any better than Arraez, and then the article answered that question

Probably fewer overall hits, but MUCH more power.