Does Swinging Less Mean Swinging at Better Pitches?

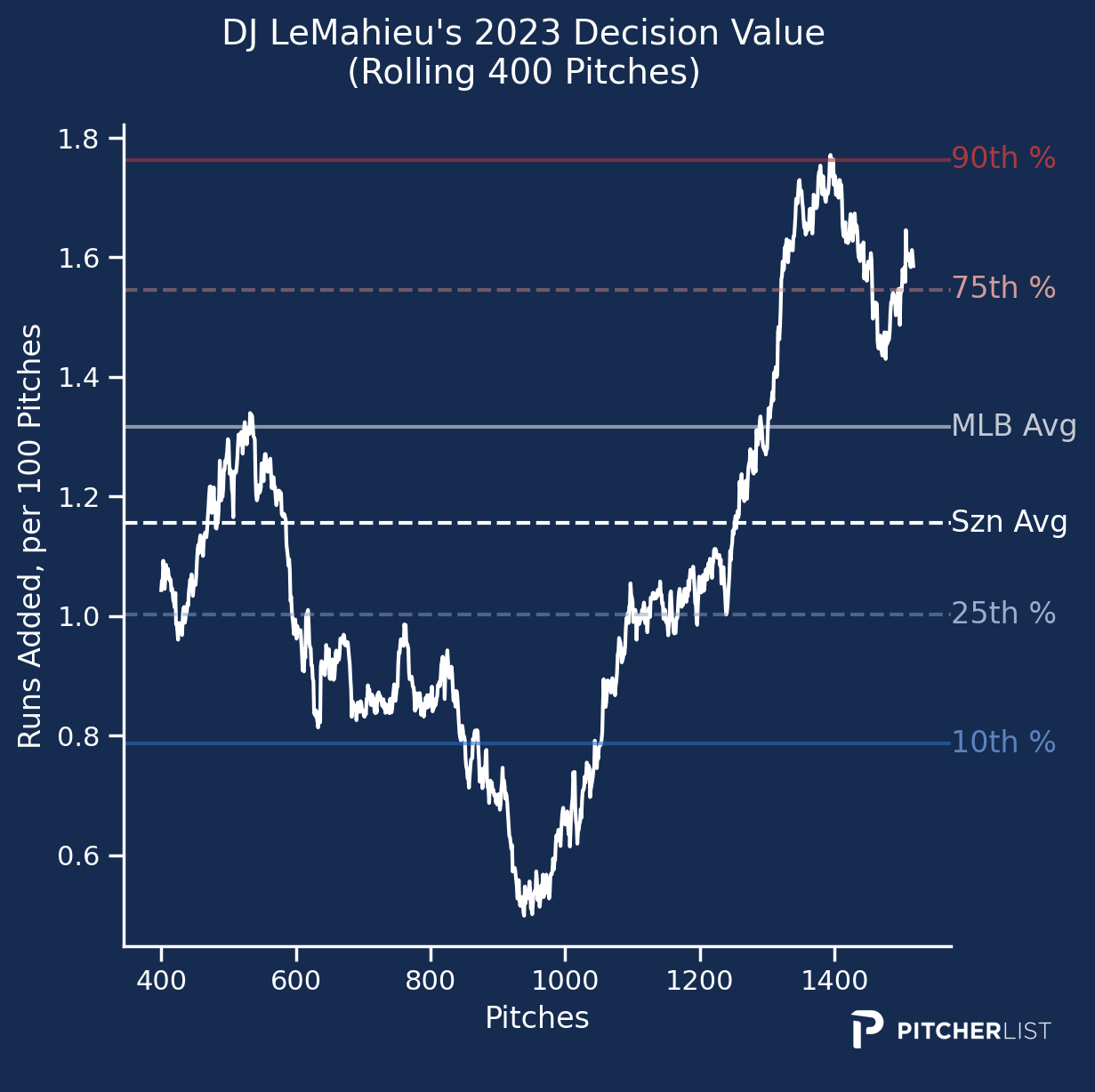

Last week over at Pinstripe Alley, I investigated DJ LeMahieu’s recent hot streak. Naturally, he got injured as soon as I finished writing, but I went through with the piece nonetheless because I felt like I was onto something. Specifically, I noticed that LeMahieu’s struggles this year came when pitchers were challenging him more; as a result, he was swinging more, but proportionally, more of those swings happened to come on balls than when pitchers were being stingy with their strikes.

When attempting to contextualize LeMahieu’s hot stretch, I noticed another hitter who’s been on fire lately thanks to some improved discipline: Ha-Seong Kim. Over the past 30 days, he’s tied for the major league lead in WAR with Freddie Freeman at 2.1. Some of that production has come from his typically excellent defense, but Kim has been no slouch with the bat either; in that span, he’s posted a 189 wRC+, eighth-highest among 167 qualifiers. Perhaps most notably, he’s also tied (with Lars Nootbaar and Alex Bregman) for the second-best BB-K rate, behind only Marcus Semien.

Prior to that 30-day stretch, Kim’s swing rate was already a career-low, and his BB-K rate near a career-best. But his swing rate has dropped even further in the last 30 days, ranking second-lowest at 34.2% to Nootbaar’s 34.1%, and his BB-K rate has gone from negative to positive; now it’s definitely a career-best. Nootbaar has followed a similar trajectory: his swing rate was already a career-low and has sunk even further, and his BB-K rate is now approaching a career-best thanks to his own torrid month.

One question this raises: are hitters more productive when they swing less? Eno Sarris of The Athletic found that generally, yes, they are. But why? Being patient and letting the ball travel can actually decrease a hitter’s home run probability; making contact out in front of the plate provides the best chance at a dinger.

Some hitters with elite eyes, like Juan Soto, can seemingly decide to swing at fewer balls without having to wait for pitches to travel more. This not only allows them to maintain their typical point of contact when they do swing, but it also leads to more high-ball counts and thus walks. But what about “bad ball” hitters? Is it worth it for them to take more walks on pitches they can drive? And what about hitters with poor eyes; if they can’t simply start taking only balls, aren’t they bound to face more called strikes as well?

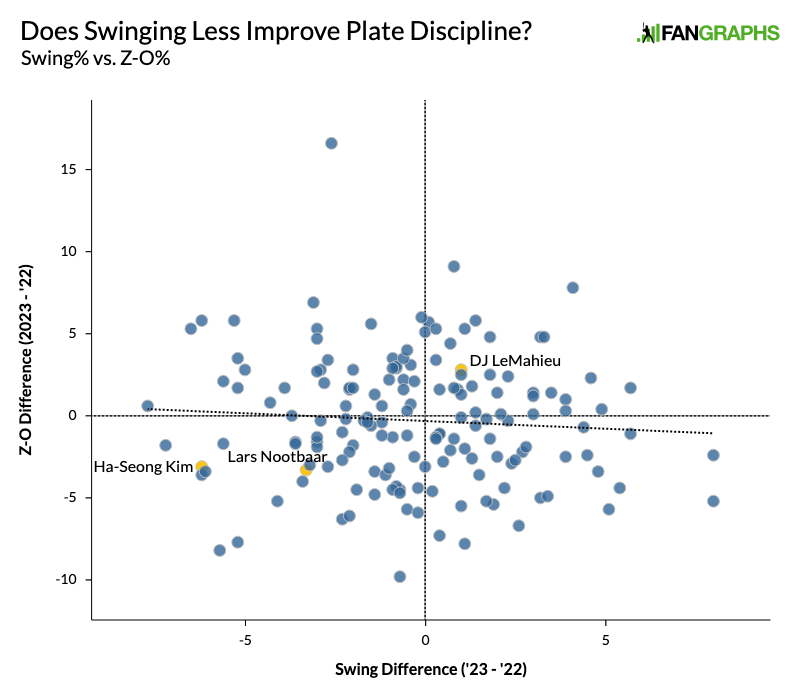

Let’s tackle that last question first by asking another: does swinging less lead to better swing decisions in aggregate? One of the more tried-and-true measures of plate discipline since the advent of PITCHf/x has been Z-Swing% minus O-Swing%, or a hitter’s swing rate on pitches inside the zone minus their swing rate on pitches outside of the zone. By this measure, LeMahieu improved during his hot, less-swingy stretch, but Kim actually got worse. Sure enough, the results year over year (for hitters with at least 300 plate appearances in each season) offer a similarly mixed bag:

On the season, Kim’s Z-O% has actually been worse than last year’s. Meanwhile, LeMahieu has actually swung more than last year on the whole, but he’s made better swing decisions through this lens. Nootbaar’s Z-O% has worsened about as much as Kim’s even though his swing rate hasn’t dropped as much. Our examples run the gamut of possibilities, and there is virtually no correlation here.

Yet in recent years, there has been an explosion of measures devoted to evaluating swing decisions. A big issue with Z-O% is that it considers all balls — from a pitch over the catcher’s head to one just above the zone — the same, as well as all strikes, from a dart on the corner to a meatball right over the heart of the plate. Baseball Savant rolled out some measures in an effort to combat this, instead divvying up pitch locations into four different buckets: heart, shadow, chase, and waste.

My colleague Ben Clemens has experimented with melding these buckets into a single swing-decision measure. It’s more helpful to conceptualize plate discipline this way than Z-O%. The average run value of a swing is only positive, and the average run value of a take is only (substantially) negative, on meatballs, or “heart” pitches. That’s not only intuitive, but also in line with Eno’s reporting that hitters would typically benefit from swinging less.

As nice as the heart/shadow/chase/waste system is for conceptualization, it’s not the most robust framework in practice. Even though it uses more categories than Z-O%, it’s still categorical, which means we’ll always be sacrificing some nuance. Additionally, it relies on contextualized run values — that is, run values that change depending on base-out situations. For example, the value of a ball in an 0–0 count will be lower with the bases empty and two down than with the bases juiced and no outs. In essence, it bakes in leverage and situational hitting, which I’m not seeking to do here.

Luckily, there are plenty of continuous measures of plate discipline out there that rely on decontextualized run value. A personal favorite of mine is based on Pitcher List’s PLV, or Pitch Level Value. PLV for pitchers resembles the pitching models we have on this site, Stuff+ and PitchingBot, and it’s where Pitcher List’s Decision Value measurement for hitters begins. PLV takes into account a pitch’s stuff (velocity, movement, etc.), location (including relative to a hitter’s height-based strike zone), and other variables such as pitch type, handedness, and count, using that information to predict whether a hitter will swing or not.

From there, the model evolves into a decision tree. On one side is what happens in the event of a swing: a model predicts whether there will be contact, and in the event of contact, whether the ball will be in play, and finally, if the ball is in play, what the result will be. On the other side is what happens in the event of a take: a model predicts whether the pitch will be called a ball, a strike, or whether it will hit the batter. Every node at the end of the tree is a final outcome: whiff, foul, hard-hit liner, etc., each with a probability of occurring and a corresponding decontextualized run value in the event it does in fact occur. The sum of all the probability*run-value products is the expected run value of the pitch.

For hitters, in the event of a swing, the sum of those end-node products on the “take” side is subtracted from the sum of those products on the swing side to lend the expected value of a swing, and vice versa for a take. This leads to one “Decision Value” number for every pitch a hitter sees. This is a far better proxy of plate discipline than Z-O%.

Additionally, there is also a “Swing Aggression” value borne from the initial model that predicts whether a hitter will swing or not based on the pitch quality and location. If a hitter swings more often than the model expects them to, they’re considered aggressive. This is an even better measurement than pure Swing% because it takes into account the pitches a hitter actually sees; no need to ruminate on whether LeMahieu was really making better decisions only because he was seeing fewer strikes over the past month. PLV says that, even controlling for the pitches he’s seen, LeMahieu has been making much better decisions as of late:

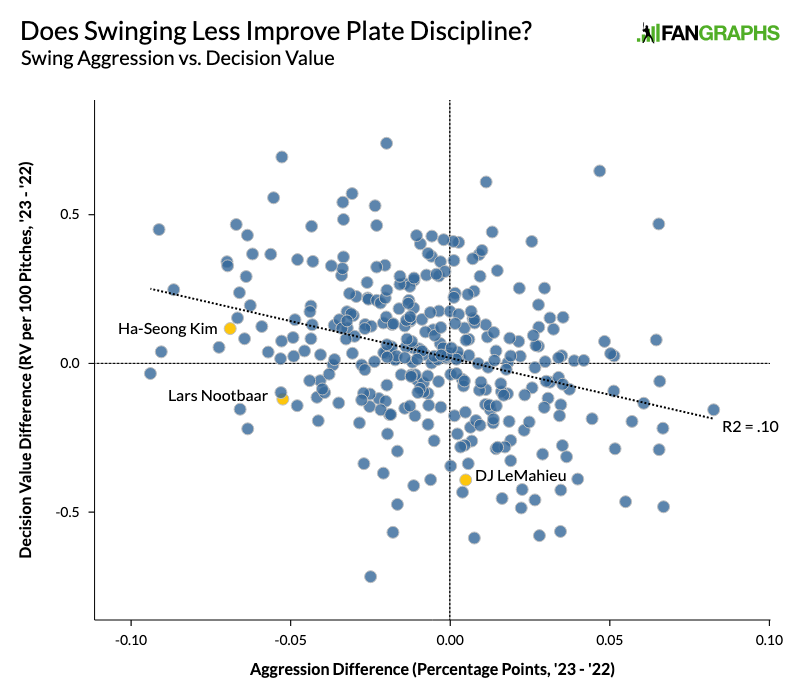

For those curious, you can make graphs like this and mess around with the higher-level swing decision stats here. But Kyle Bland, PLV mastermind, was kind enough to provide me with more granular data, which I’ll use to test out my theories. After this long-winded explanation, let’s get back to the question I was asking in the first place: does swinging less lead to better swing decisions? Controlling for the types of pitches hitters see (i.e., using the Swing Aggression metric), the answer is yes:

For a variable as nebulous as Decision Value, the ability of aggression to explain even 10% of its variance (as denoted by R-Squared) is impressive. But there are many exceptions to the rule. LeMahieu’s poor decisions when pitchers were challenging him really tanked his score. Kim, meanwhile, easily bested Nootbaar in terms of decision improvement even though they were neck and neck when it came to Z-O%, but even he was below where we’d expect given his decrease in aggression.

The overarching reason that swinging less leads to better decisions, even for hitters who see more called strikes than additional balls as a result of being less aggressive, is that swinging at strikes generally leads to worse outcomes than taking, with meatballs and two-strike pitches being the exception. Now, this isn’t to say that swinging less makes a hitter better at discriminating between balls and strikes; in fact, on non–two-strike pitches, that doesn’t seem to matter as much as discriminating between pitches to hit and pitches to lay off. Every hitter has a different subset of offerings that fall under the “pitches to hit” umbrella, a subset that often changes throughout the course of a season as hitters and pitchers adjust and readjust to each other.

Because of their dynamic nature, it would be hard to include individual pitch preferences in a stat like Decision Value. Instead, they might make sense as a separate metric, something like the personalized good versus bad decision rates that Robert Orr developed over at Baseball Prospectus. For now, I’ll offer you this: Kim has graded out well in terms of his Decision Value improvements, but he still lies below the fit line in terms of his expected improvement based on his drop in aggression. One potential reason: he’s still prone to fishing on pitches in and off the plate:

I’m not sure I’d mess with a good thing, but it seems to me that there’s a pretty obvious fix here. Kim has a slightly open stance, so the inside pitches look pretty appetizing. But while his stance is open, he’s still a ways off the plate; if he crowded it a bit more, his heat map would shift over one square, and he’d be swinging at a lot more strikes without having to change his stance or mechanics. Kim, who was an offensive force in the KBO before he came stateside, has yet to reach his offensive ceiling; combining heat-map driven insights with decision-value modeling could help both the Padres’ second baseman and the analysis of plate discipline reach new heights.

Stats are as of end of day Sunday, August 13.

Alex is a FanGraphs contributor. His work has also appeared at Pinstripe Alley, Pitcher List, and Sports Info Solutions. He is especially interested in how and why players make decisions, something he struggles with in daily life. You can find him on Twitter @Mind_OverBatter.

Why do you think Asian player’s names are flipped in baseball media? I don’t see this happen in other forums (politics, acting, other sports). Wouldn’t it be better to present their names in the traditional manner?

I think Korean names are the exception that proves the rule: Ban Ki-moon on the one hand, but Haruki Murakami and Yao Ming on the other.

Fangraphs seems to compromise a little when it comes to the KBO, where it presents names in the Western order and then the Hangul after. Curious why this doesn’t carry over for Korean players who come stateside.

Yao Ming (姚明) is in the traditional eastern order, Yao is his family name. But that kind of makes my point, it is not always easy to discern family name from given at a glance. It feels to me like keeping the Asian order would be easier to understand and more culturally sensitive to boot.

The order in which you put a surname is a matter of convention, so in general, where the audience expects the surname to be is where you should put it, along with explanations, if necessary, to dispel any confusion.

It does happens in other forums like entertainment (Chan-Wook Park, for example), though it isn’t uniform in any context.