Fastballs? We Don’t Need No Stinking Fastballs

It’s hard for me to explain how much I enjoy watching Mookie Betts hit. He has an air of quiet confidence that reminds me of how I feel when I’m at my very best. That slider, low and tight? He doesn’t need it, so he’s ignoring it. Fastball away? Eh, he’ll find something better to attack. Then that perfect pitch comes by, and he springs into action, trading his air of barely concealed boredom for ferocity.

Luis Robert Jr. is a joy to watch as well, but for completely different reasons. He’s a coiled spring at the plate, waiting to burst into action. He’s one of the best athletes in all of baseball and at times one of the best players, period. His phenomenal bat control and speed let him feast on pitches all over the plate and even off of it, and you can see it in his statistical record: few walks, huge swing rates, and a minor strikeout problem that was minor only because of his rare combination of power and contact.

Betts and Robert have been very different players in their respective major league careers. But they share one distinction this year: they’re the two players who have cut back on their fastball swing rates the most. They’re numbers one and two with a bullet:

| Player | 22 FB Swing% | 23 FB Swing% | Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Luis Robert Jr. | 62.0% | 49.1% | -12.9% |

| Mookie Betts | 43.7% | 31.3% | -12.4% |

| Rowdy Tellez | 42.7% | 32.8% | -9.9% |

| Manuel Margot | 52.1% | 42.4% | -9.7% |

| Wander Franco | 49.0% | 39.3% | -9.7% |

| Ian Happ | 46.8% | 37.8% | -9.0% |

| Brandon Marsh | 47.8% | 38.9% | -8.9% |

| Mike Yastrzemski | 43.4% | 34.5% | -8.9% |

| Pete Alonso | 49.1% | 40.4% | -8.7% |

| Nathaniel Lowe | 53.1% | 44.5% | -8.6% |

That’s weird, isn’t it? The two have very different games, and they’re both excelling this year by leaning more into their type. Betts is getting back to what he’s always done best, walking a ton and putting the ball in the air with abandon when he does deign to swing. Robert has already tied his season high for home runs — it’s May 23 today — and is striking out a little more than you’d like without many walks. And they’ve both done it by making the same adjustment.

For Robert, swinging less always felt like a logical progression. Swing-happy isn’t a sufficient description of his approach; he led all of baseball in fastball swing rate last year. He swung more frequently at pitches outside of the strike zone than Betts swung at pitches overall. It wasn’t a fractional difference, either: Robert’s 48.3% chase rate would make Javier Báez blush; Betts offered at only 44.2% of pitches.

Opposing pitchers know that about Robert, and they’ve always had one counter in mind: throw him more sliders. Nearly 30% — 29.7%, to be exact — of the pitches he’s seen in his major league career have been sliders. That’s the highest rate among active players, and likely the highest rate ever. It’s no secret: he does so much damage when he connects, and swings so frequently, that throwing bat-missing breaking balls is the only reasonable counter.

Pitchers have leaned into this plan more and more over the years. This year, there’s almost no such thing as a fastball count for Robert. In 0–0 counts, he’s seeing four-seam fastballs and sinkers — cutters are somewhere in between, and so I’ve left them out of this analysis entirely — only 47.1% of the time. That’s a bottom quartile rate, and even when pitchers are behind in the count, they only throw him fastballs half the time. Robert has always killed fastballs, but swinging a lot against fastballs also meant swinging a lot at everything, and the mix was simply too breaking-ball-heavy.

This year, Robert is swinging at only 29.1% of first pitches. In his career before this year, that number was 51.8%. This isn’t him tinkering around the edges; he’s completely changed his game. No one in baseball has cut their swing rate by more. He still doesn’t have elite, Betts-level pitch recognition. To wit, he’s cut his swing rate on sliders by only 4.7%. But the intent is clear: Robert wants to swing less, which should force pitchers to engage him on his turf more frequently.

The plan is working phenomenally well. Robert has produced more runs above average than any other hitter in baseball against four-seamers this year, and he’s top 20 for fastballs in aggregate. As it turns out, letting the occasional fastball go by without a swing is no big deal for him, because the ones he does offer at tend to disappear into the outfield air rapidly. Ask pitchers how they feel about throwing Robert a fastball. Just because he swings less often doesn’t mean he never swings, and no one wants to give him a chance to show off his prodigious power.

An amusing result of Robert’s new approach: he’s never been ahead in the count more frequently than this year. Despite that, he’s striking out more than last year. Why? Running deeper counts means more strikeouts, even if you have a great batting eye. But it also means more chances to swing in advantageous counts, and the loud contact he’s making on those counts is more than making up for any extra strikeouts.

Most likely, Robert’s current approach is an unstable equilibrium. Pitchers will probably start throwing him more first-pitch fastballs at some point. It’s almost dangerous not to, when he’s swinging so infrequently at first pitches and then hunting for something crushable thereafter. Faced with that, Robert will have to swing more; it’s almost dangerous not to, when those might be the best pitches he sees in the whole at-bat. But then pitchers will have to start throwing him fewer strikes — it’s almost dangerous not to — and then he’ll have to swing less frequently, and so on and so on.

All of this back-and-forth is interesting, and yet it’s completely unlike what Betts is doing. He doesn’t see a particularly low number of fastballs — he sees more than league average, in fact. He didn’t need to adjust his plan to keep pitchers from exploiting him; it’s been working well for a decade. Yet there he is, at the top of the fastball swing decliners list next to a guy who badly needed to rein in his aggression.

Look a bit closer, and Betts’ numbers get extremely interesting. Last year was a vintage Betts year — his best season as a Dodger — but he had some un-Bettsian tendencies under the hood. In fact, he swung more frequently than he ever had in his career. That adjustment had predictable effects: he walked less often and struck out slightly more frequently, but he punished the extra fastballs he swung at. He’s never turned fastballs into extra-base hits as frequently as he did last year, at least in terms of extra bases per fastball seen.

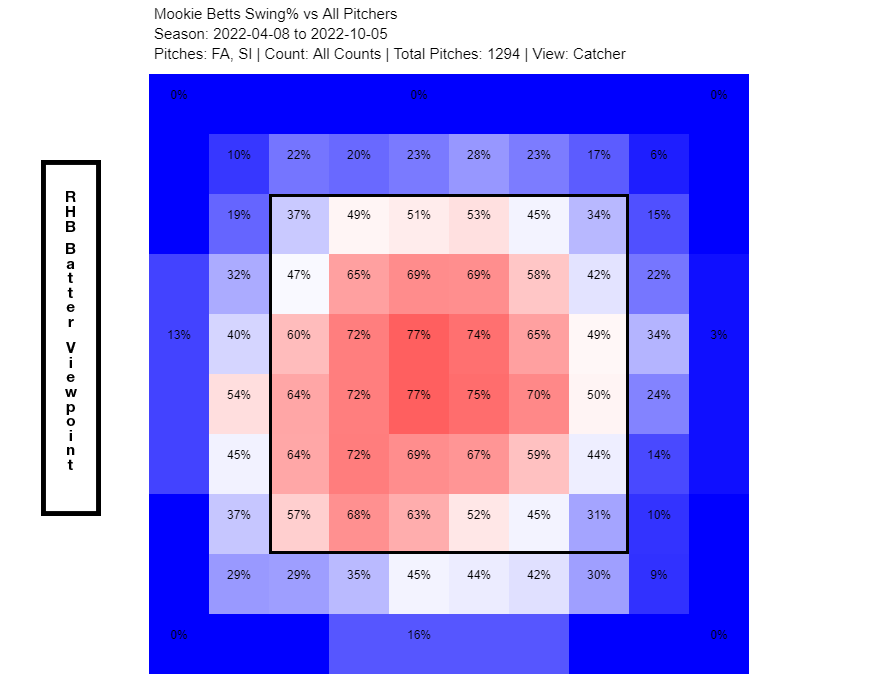

What made Betts change his fastball-attacking ways? For this one, I’ve got some charts. Here’s where he swung at fastballs last year:

Not bad, not bad. You can see more red than is probably ideal on the periphery of the zone, but c’mon, he’s Mookie Betts, he’s good at hitting. It’s a nice heat map.

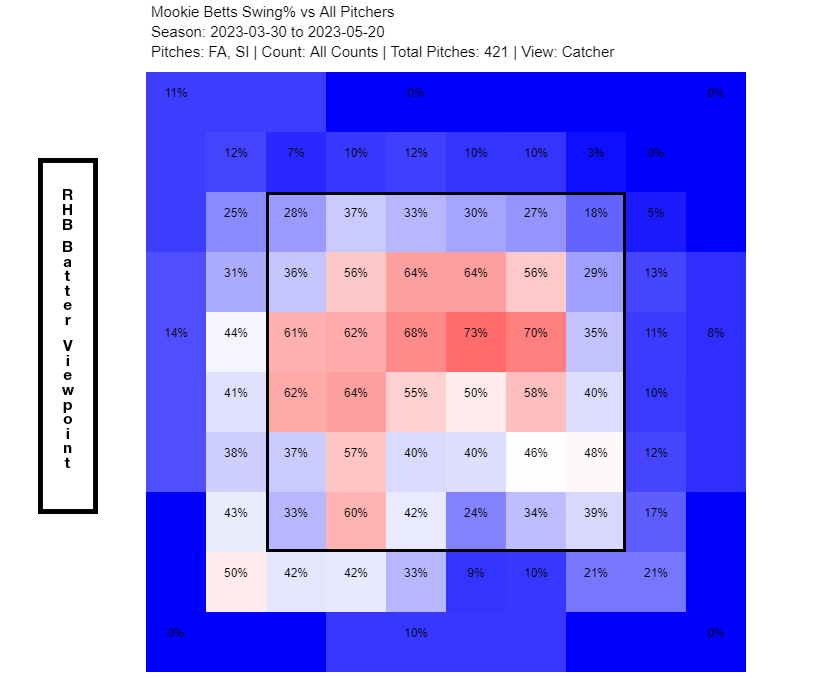

But here’s a really nice heat map, his fastball swings in 2023:

That’s downright gorgeous. He’s still swinging a ton when pitchers give him something to drive, but he’s chasing fastballs a microscopic 10.5% of the time, the third-best mark in baseball. Any decrease in swings over the heart of the plate is offset by fewer swings at marginal pitches.

Can I tell you a secret about Mookie Betts? He’s a feared hitter, but it’s not because he smacks fastballs out of the park. Since joining the Dodgers, he’s hitting .320 with a .628 slugging percentage when he puts a fastball in play. That’s good for a .396 wOBA, roughly average among everyday hitters. This isn’t a Juan Soto situation where swinging at fewer fastballs means less chances to show off Home Run Derby power; it’s definitely worth giving up on the occasional middle-middle fastball in exchange for a ton of extra balls. Heck, Betts has a .373 wOBA *overall* in Los Angeles. He doesn’t need to sell out to swing at fastballs; he can pick and choose ones he thinks he can obliterate.

“Swing at fewer fastballs” doesn’t sound like a good plan. But two great hitters are each doing it this year, and they’re both having excellent seasons. Neither of them is doing it for the sake of swinging at fewer fastballs; in both cases, fastball swing rate is a side effect. Robert needed to rein in his overall swing-happy ways. Betts wanted to focus on swinging at better pitches to drive. They might have the same input (fewer swings at fastballs) and the same output (solid offensive production), but the way they get from A to B is completely different.

The moral of the story: great baseball players don’t all play alike, and even when they make the same adjustments, those adjustments don’t all do the same thing. Luis Robert is nothing at all like Mookie Betts. He’s also a lot like Mookie Betts, if you’re looking at them in one particular way. Isn’t baseball great?

Ben is a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @benclemens.

Baseball is so cool