Hunter Goodman Isn’t Choosy

Hunter Goodman isn’t going to chase forever. We’re not even two weeks into the season. All the players with .400 batting averages will come back down to earth, and so will Goodman and his 54.1% chase rate. That’s right, I said 54.1%. If you’re a pitcher who misses the strike zone, odds are Goodman will help you out by swinging anyway. Sports Info Solutions has been tracking pitches since 2002, and in that time, no qualified player has ever run a 50% chase rate over the course of a whole season. Hanser Alberto reached 54% during the short 2020 season and Ceddanne Rafaela gave it his best effort in 2024 with a 49.5% mark (just ahead of 2023 and 2025 Salvador Perez), but that’s it. Goodman won’t stay above 50% either, but he is on a record pace at the moment, and his 66.1% overall swing rate is even further ahead of Randall Simon’s all-time record of 63.6% in 2002.

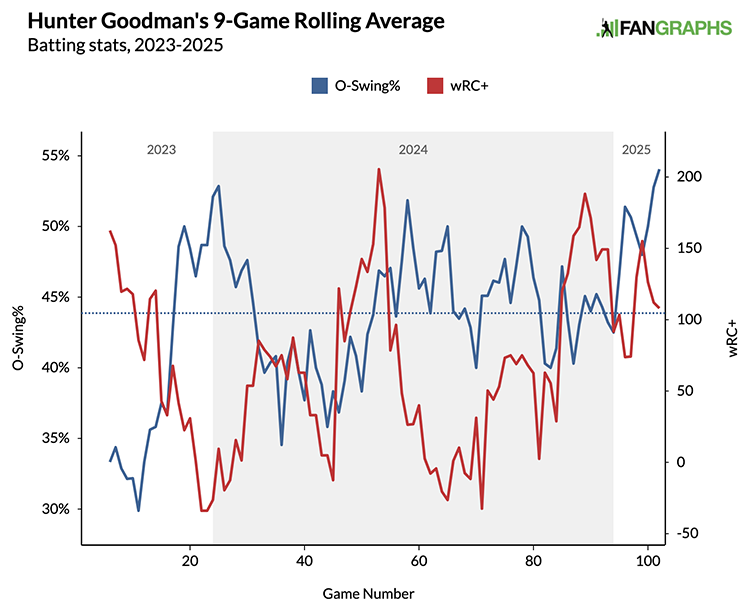

I’m less interested in whether or not Goodman will set a record – he probably won’t – and more interested in what’s going on with him right now. Coming into the season, his career chase rate was 42.8%. That’s plenty high, and it included some nine-game stretches in which he at least approached this level. But for the most part, when he was chasing at an extreme rate, his performance cratered, just like you’d expect.

When the blue chase rate line went up, the red wRC+ line went down. But that seemed to change toward the end of the 2024 season. I don’t think it’ll last, but at the moment, Goodman is running a 109 wRC+ despite an appalling dereliction of discernment. It’s not necessarily that he can’t tell the difference between a ball and a strike. As I write this on Tuesday, there are still five qualified players who haven’t walked at all. Goodman is not one of them, nor is he one of the 149 players who’s swung at a pitch in the waste zone.

Statcast’s numbers aren’t quite as extreme as SIS’s. Goodman is still in front, but his chase rate is at 52.4%. He’s seen 63 pitches outside of the zone and he’s swung at 33 of them. Knowing that, I did what any rational person would do. I watched them all. I started with the takes, which consisted of 29 balls and one called strike. You can watch them too. It does not take long. Before I watched, the question I most wanted to answer was about the feel. If I watched Hunter Goodman do nothing but take pitches, would I come away from the experience with the incorrect sense that he was a guy who took lots of pitches? Or would I have the correct sense that this was a man who was just barely keeping his demons at bay?

Watching all these back-to-back, what strikes me is that Goodman really wants to dive into the ball. He’s looking middle-away, and he gets started early. There’s a smattering of check swings, but a lot more pitches where he fires his hips, drops his hands, and starts his trunk rotation only to stop abruptly. One way to make sure that you run a high chase rate is to go up there looking to swing, and Goodman wants to badly. Clearly, he’s defaulting to swing mode, and it feels a little bit like a car crash every time he forces himself to stop. If you’ve ever blown a circuit breaker on a hot summer day and heard an overmatched window air conditioning unit come screeching to a halt, some of these takes will feel familiar.

A lot of these pitches, especially the comfortable takes, are inside pitches from left-handers, which is to say that they have an extreme horizontal approach angle. They look like they’re coming right at Goodman, especially because he starts every pitch by preparing to dive into the strike zone. That’s what it takes to keep him from swinging at a pitch right now: fear of grievous bodily injury.

I watched all of Goodman’s chases next.

Well, you can see why Goodman starts his swing so early. He’s behind on an awful lot of pitches. Either he’s swinging under fastballs or they’re getting in on his hands and he’s chopping them down the third base line. When the ball’s away, things are even worse. That’s the real danger of diving out over the plate and looking for the ball on the outer third: That’s where all the breaking pitches start. Goodman ends up swinging at lots of sliders and curveballs that look sweet and juicy, but only for a moment. When these breaking pitches inevitably dive toward the dirt or dart way outside, he’s already swallowed the bait.

You may have noticed that I dodged a question earlier. When I watched all those videos of Goodman taking pitches outside the strike zone, my goal was to see whether it was obvious that he was the game’s most reckless swinger. I wish I had a better answer for you. I told you about all the patterns I recognized, but if you’d showed me that first video without any context, would I have known that this batter was on pace to set a record for unchecked aggression? I doubt it. This is about as extreme as baseball gets, but for the most part, it still just looks like baseball. You can definitely tell that there aren’t many close pitches here – when a pitch is bad enough for Goodman to lay off it, it’s awfully bad – but I’m not sure I would have clocked that without being primed to look for it.

The chases tell a different story. Goodman has sort of an odd swing. He ranks 22nd in baseball with a bat speed of 75.4 mph, and although his swing looks loopy when you watch it, Statcast pegs its length at 7.2 feet, well below average. That’s because his hands seemingly don’t move backward at all during his load, but he does have a pretty extreme follow-through. Excellent bat speed and a shorter swing should be a great combination. Goodman is swinging harder than Vladimir Guerrero Jr., and his swing length is as short as Corbin Carroll’s. However, even in the zone, Goodman doesn’t make a ton of contact. As with so many things, there’s a tradeoff going on. I’m by no means an expert in swing mechanics, but my eyes tell me that Goodman is not generating all that power by way of a long, rotational swing, but rather by way of a linear, max-effort swing. Even when he was in college at Memphis, his load was extraordinarily quiet. So although the bat head doesn’t travel particularly far, it takes time and effort for it to get up to speed from a standstill. It’s a different kind of swing length, having to do with time rather than distance. Starting early and putting so much energy into it at the very start makes it much harder to stop. Most of the time, Goodman’s just not stopping.

Davy Andrews is a Brooklyn-based musician and a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @davyandrewsdavy.bsky.social.

Great article, love the videos! Would be interesting to find another player to compare/contrast to.