Introducing the New Orioles Bullpen

On April 15 at Camden Yards, the Orioles and Yankees were locked in a stalemate. Both starters had exited, and by the seventh inning, the score remained tied, 1–1. It would be up to each team’s bullpen to keep the game close until their respective bats came alive. The Yankees, of course, sported the league’s finest collection of relievers, a sentiment shared by our preseason positional power rankings. The Orioles bullpen, in contrast, had been deemed one of the league’s worst. A lack of offensive firepower also cast a shadow of doubt on Baltimore’s hopes for victory. It was clear: One side had the advantage, the other did not.

And yet, it was the Orioles who triumphed to secure the win. The projected 28th-best bullpen held its own until the 11th inning, when Ramón Urías drew a walk-off walk against a shaky Aroldis Chapman, bringing a drawn-out conflict to a close. But this isn’t just a one-time, David-beats-Goliath story. As of this writing, the Orioles have the most valuable bullpen in baseball by WAR (I know, it’s early for that, but bear with me). They have the second-most effective bullpen by xFIP. And to really put things into perspective, here’s a comparison between the Orioles and the Yankees:

| Metric | Orioles | Yankees |

|---|---|---|

| ERA | 2.75 | 2.44 |

| FIP | 2.95 | 3.07 |

| xFIP | 3.27 | 3.56 |

| K-BB% | 14.8% | 14.0% |

| CSW% | 29.9% | 29.6% |

As expected, the Yankees bullpen has served the team well. But on most fronts, the Orioles’ own unit has kept pace, a fact we can appreciate regardless of how the team is performing. Sure, that’s more mirage than reality. Skeptics can point to an abnormally low home run rate and the fact that it’s early – the Orioles had yet to face a revitalized Mike Trout until Sunday, for example. Consider, though, that Orioles relievers not only own the league’s fifth-highest groundball rate, but also its lowest fly ball rate. In tandem with the altered dimensions of Camden Yards, there’s reason to believe this contact suppression isn’t merely a fluke. They’ve set themselves up for success, in other words.

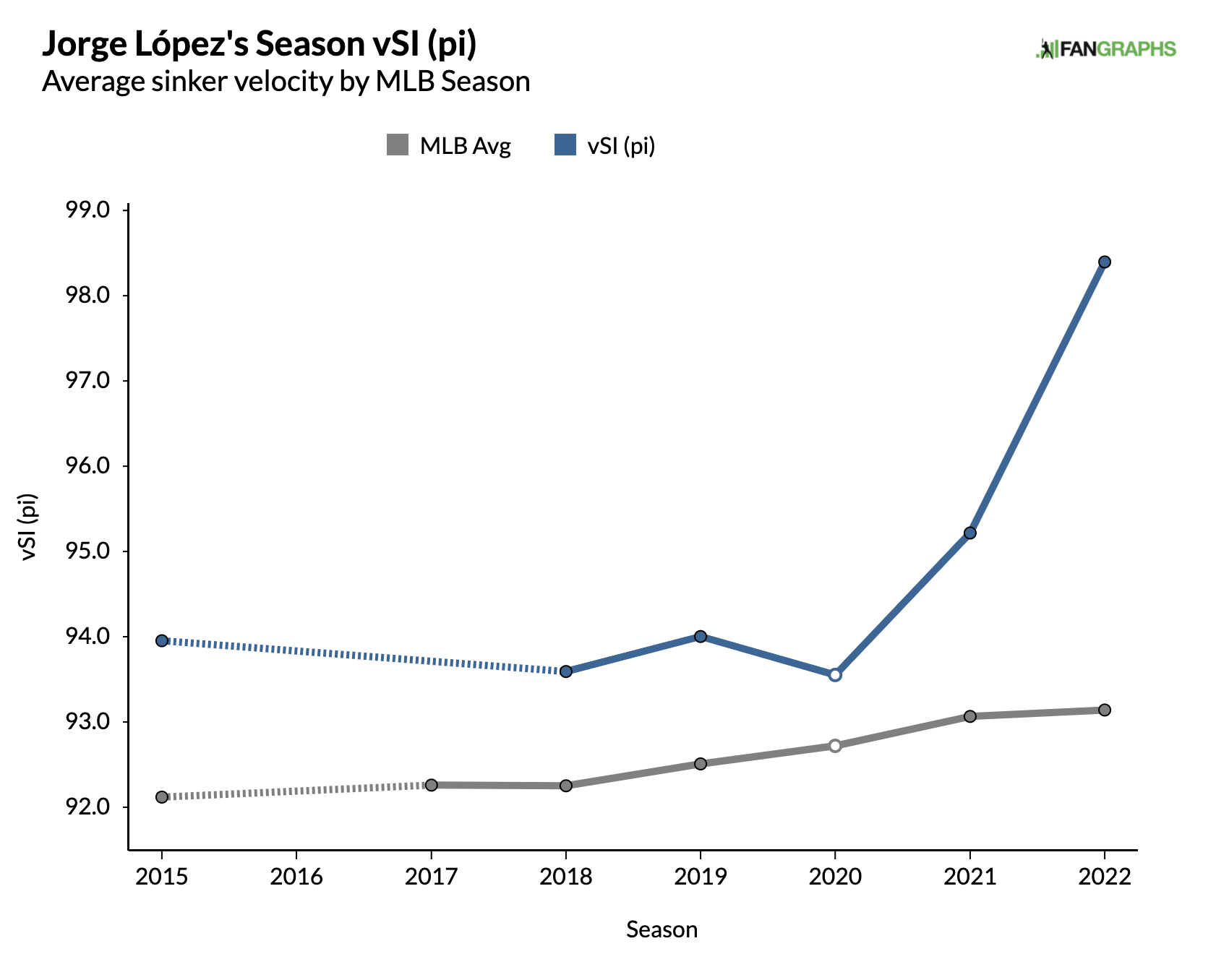

But in order to maintain a superb strikeout-to-walk ratio while eschewing the long ball, you have to have enough stuff and command. And in the Orioles bullpen, you’ll find plenty of both. It all starts with an unlikely closer: Jorge López. A former swingman who primarily consumed innings for pitching-starved teams, López became a permanent fixture of the bullpen this season and was soon thrust into high-leverage situations. There’s a reason why the Orioles trusted him, though. Check out the change in his sinker velocity over the years:

A once slightly above-average pitch by velocity is now touching speeds that are downright scary, a development likely facilitated by a reduced workload. But beyond adding a few ticks, López seems to have realized just how good his sinker is. This season, he’s throwing it more than ever while essentially abandoning his four-seamer, whose suboptimal shape made it susceptible to hard contact. It’s incredibly rare for any pitch, let alone a sinker, to achieve the triple threat of velocity, movement, and (presumed) seam-shifted wake. López’s heater now fits that bill perfectly: It’s fast, breaks in both directions, and undergoes a significant shift in spin axis as it approaches home plate.

And we know all three elements help a sinker generate groundballs. They’ve indeed been his speciality so far, with 60% of contact against him hitting the ground. So López has gained a viable way to minimize damage on contact, and that uptick in velocity is also benefitting his secondaries without a corresponding decrease in movement (faster pitches tend to drop less). If that isn’t closer material, I don’t know what is.

Speaking of pitchers who are throwing harder, meet Mike Baumann. After averaging 93.6 mph on his four-seam fastball last season, the young righty is now sitting 95–97. Somehow, that’s not the only way he’s become better. Baumann has added nearly four (!) inches of ride to his fastball, which seems impossible, but apparently isn’t. By most measures, an already good heater has become one of the league’s best. And like López, Baumann hasn’t lost any downward break on his breaking pitches as a result of throwing harder.

Keegan Akin, who will remain in a long-relief role despite news of John Means requiring Tommy John surgery, has only added mild amounts of velocity, but he’s accomplished a feat that’s equally bonkers. His fastball velo is up by a tick and so is the pitch’s ride in inches, which is always a welcome sign. The real kicker, though, is Akin’s curveball: While he’s thrown it just five times so far, we can’t ignore that it’s dropping 11 inches more than it did last season. His four-seamer, slider, and changeup troika should hold up on its own, but if Akin decides to lean on what appears to be a new plus pitch more often, it could spell trouble for his opponents.

As Brian Menéndez documented, Felix Bautista is the new king of fastball ride. Seriously – scroll through the PitchInfo leaderboards on Baseball Prospectus, and you’ll find that no other pitcher with a 50 pitch minimum generates as much vertical movement as Bautista does. He throws that majestic heater for strikes, and batters have a difficult time squaring it up. Let’s admire, for a movement, just how unwavering his fastball can be:

It’s like the ball is traveling in a straight line from Bautista’s hand to the catcher’s mitt! And yes, he throws hard as well – 97 on the gun is typical for him. As a modern-day reliever, Bautista hits all the right notes: He throws from an extremely vertical arm slot, creates a flat approach angle, and doesn’t shy away from the zone. Not to mention that his slider, while not nearly as impressive, nonetheless has a ton of bite and separates itself from the fastball, leading to plenty of confused swings. The stuff is good, folks.

After spending the offseason at Driveline, Dillon Tate came into 2022 with promises of sharper stuff and refined command. In regards to the first, we can observe a couple of changes, though not to the extent that was advertised. For one, Tate has yet to throw the hard, cutter-like version of his older slider he reportedly developed in his Driveline sessions. He’s introduced a sweeper that’s all the rage nowadays, but it’s sluggish and breaks noticeably less compared to other, more refined sweepers. It’s safe to say that in terms of new tools, Tate is still a work in progress. Overhauling one’s arsenal takes time, and it’s natural for a pitcher to emerge from an offseason with incomplete ideas.

But in regards to the second, there are signs of promise. For someone who walked three batters per nine last season, it’s a remarkable improvement to have issued just one so far. It’s early, sure, but there’s some evidence to back it up. When Tate fell behind in the count in 2021, he responded with a strike 53.9% of the time. This year, that rate is up to 63.2%. Disadvantageous counts are harmful, but Tate has managed to minimize the damage by trusting his stuff. And why shouldn’t he? His sinker is solid to great (with seam-shifted goodness), and his changeup is a wicked offering that Tate is relying on more than ever. All that’s left is for the strikeout rate to take off, but with the strides he’s making, that’s perhaps not too far away.

Even a guy like Paul Fry, who’s struggling to open the season, offers plenty of intrigue. First, he’s a lefty, and every arm barn needs one of those. But more importantly, he twists his body mid-delivery to create an unusually low, three-quarters slot, from which Fry can unleash one of three pitches: a four-seam fastball, a slider, or a changeup. The star of the show is the second pitch, the slider. It’s a highly effective sweeper, but – and this is what’s amazing – it also comes with an amount of vertical drop typically associated with traditional sliders. The result is one of the filthiest breaking balls around:

Other significant contributors include Bryan Baker, Joey Krehbiel, and Cionel Pérez, each of whom is in possession of at least one trait that makes him stand out. Baker has a weird cutter-slider hybrid that eludes classification and catches hitters looking due to its atypical movement. Krehbiel’s own cutter behaves similarly, and his changeup, which he’s been using this season as a primary pitch, has the fourth-most vertical drop among righties. The players above him are names you might recognize, like Logan Webb and Devin Williams. Meanwhile, Pérez’s slider is almost identical to Fry’s… and his heater casually hums in at 96 mph.

Until now, I’ve mostly talked about what makes each pitcher special. But tying the bullpen together is a recent shift in philosophy, one that challenges the very notion of a catcher’s role. This season, Orioles catchers are setting up in the middle of the plate. The idea: On average, pitchers tend to miss their spots – by a lot. So when catchers provide a specific target, it can actually induce the pitcher to completely miss the zone. But with a central target, those same mistakes help a pitch become a strike. For example, if thrown towards the strike zone, a good 12–6 curveball would veer towards its bottom edges. A hard four-seamer would end up higher, and so on.

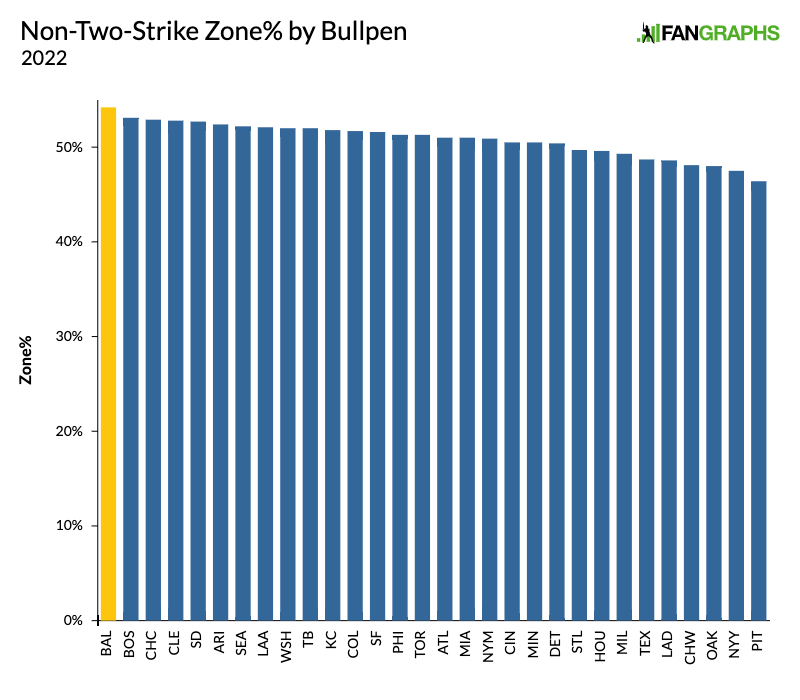

There’s evidence that this is working. With a one-target approach, it’s usually the case that catchers will return to traditional setups once two strikes are established. Using Baseball Savant, I looked at each bullpen’s zone rate this season in non-two-strike counts. Here’s that represented in graph form:

The Orioles are on top. That doesn’t mean throwing strikes always correlates with success – the Dodgers are 26th by zone rate, and the Yankees are 29th – but it’s been working for Baltimore. This is a bullpen that struggled to find the zone last season. Now they’re attacking it with an uptick in stuff, getting ahead in counts and inducing hitters to chase afterwards. In an age when it’s perfectly acceptable to throw quality pitches down Broadway, the Orioles have demonstrated the value in realizing that making contact with a baseball is dang hard, even for skilled hitters.

Because it’s April and some people will be asking: No, I’m not claiming the Orioles have constructed a mega bullpen on the fly. The strikeouts aren’t quite there, and just because a pitching staff suppresses fly balls early on in the season doesn’t mean they will later. There will be blow-ups, moments when fans collectively wonder if this is rock bottom. What’s abundantly clear, however, is that this is a better bullpen than it was before. López has been a revelation, but if you’re willing to pay attention, so has Bautista, Baumann, Krehbiel, and a few others. The O’s got nastier, a fact they’ve leveraged to steal strikes. They won’t be in first for long, but they are now. As is turns out, that isn’t just a coincidence.

Justin is an undergraduate student at Washington University in St. Louis studying statistics and writing.

Wow.

It’s been insane to watch as an Orioles fan. We haven’t had a good arm barn since what, 2016?