Jacob Lopez Is Doing a Credible Chris Sale Impression

Straight away, I wrote Jacob Lopez off. Even as he strung together three incredible starts in June — 32% strikeout rate, one run allowed over 19 innings — I couldn’t bring myself to think it actually meant anything. A 27-year-old lefty with hardly any prospect pedigree and so-so command throwing 90 mph dead zone fastballs? Small sample weirdness, nothing to see here.

It’s harder to dismiss Lopez these days. Once again, he’s on an infernal heater, this one even more scalding than the previous iteration. His last three starts: five innings, no runs, five strikeouts against the Diamondbacks; 7.2 innings, no runs, 10 strikeouts against the Nationals; seven innings, no runs, nine strikeouts against the Rays. That’s a 34.3% strikeout rate and a 0.98 FIP in a 19.2 inning sample.

Some of this is the quality of the opposition; the Rays and Nationals have been among the worst offenses in baseball over the last month or so. But the overall sample is getting uncomfortably significant. Over his 84.2 innings pitched this year, Lopez holds a 28.9% strikeout rate, eighth — eighth! — among all pitchers (minimum 80 innings pitched). He’s striking out more hitters than Paul Skenes, Jacob deGrom, and Spencer Strider.

And Lopez isn’t just missing bats; Baseball Savant puts him in the 95th percentile in terms of hard-hit rate, the 94th in average exit velocity, and the 82nd in barrel rate. A pitcher who gets whiffs and reliably generates weak contact is in a rare class. Here is the entire list of starters (minimum 1,000 pitches) with at least a 28% strikeout rate and a sub-88 mph average exit velocity allowed: Skenes, Tarik Skubal, Hunter Brown, Zack Wheeler, Garrett Crochet, Chris Sale, and Lopez. That is pretty close to a list of the best pitchers in the sport, and also Jacob Lopez.

Is there any sort of precedent for someone pitching at this level with such uninspiring stuff? Well, not really, at least not among Lopez’s contemporaries. But for a reasonable point of comparison, look no further than the second-to-last name on the aforementioned list.

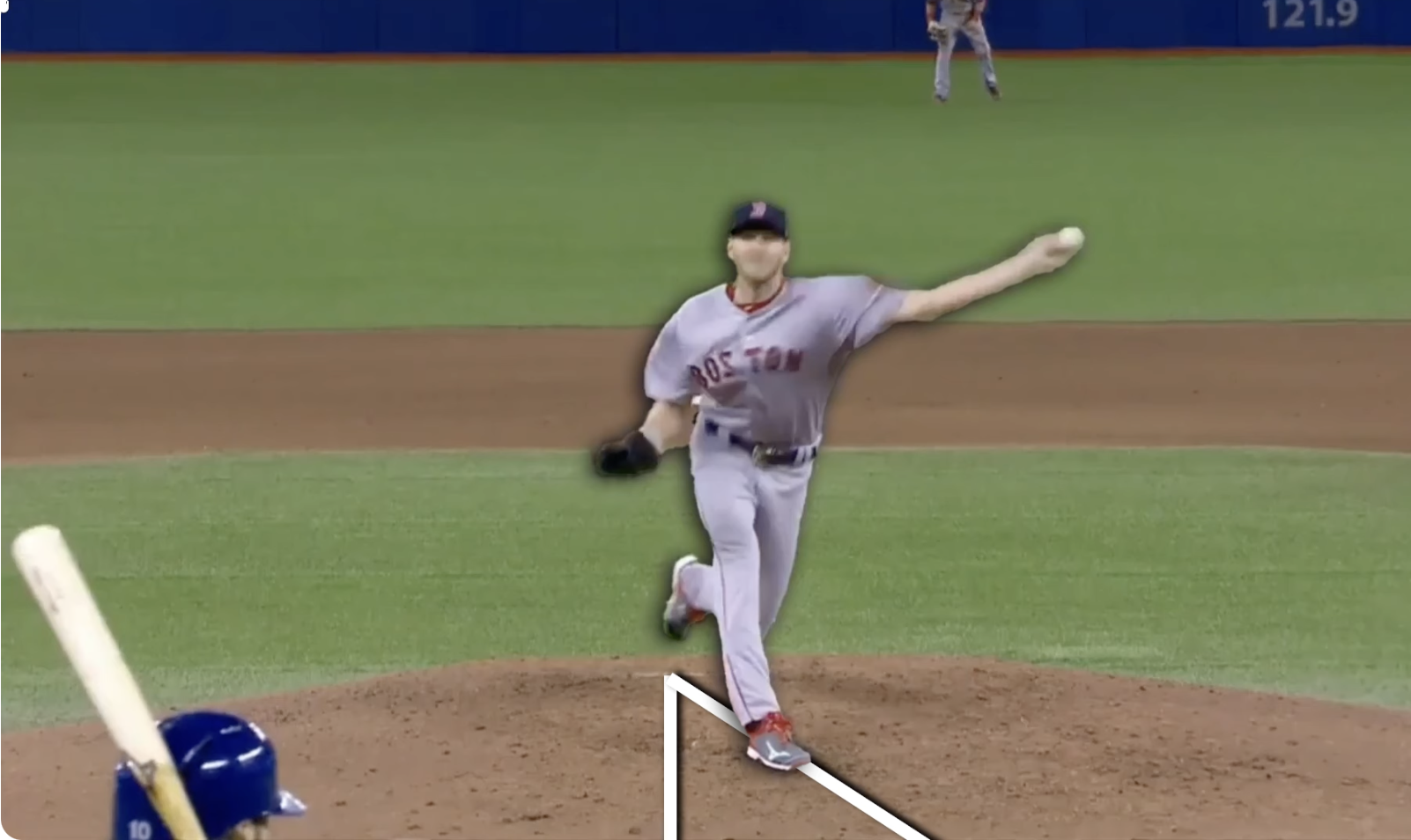

Sale is a likely Hall of Famer and delivered the finest season of his career in last year’s age-35 campaign, posting a 2.09 FIP while striking out 32.1% of hitters over 177.2 innings. He nearly matched that level this year prior to hitting the IL in July. And he’s done it all while stuff models shrug their shoulders.

Certainly there’s an argument to be made that Sale’s stuff is anything but mediocre, but, hey, the stuff models say what the stuff models say. This year, PitchingBot gives Sale’s fastball a 48 on the 20 to 80 scale and his trademark slider a 49. Stuff+ agrees on his fastball, grading it a 97 on a scale where 100 is average, though it likes his slider a good bit more (117 Stuff+).

While Sale sits 95 mph with his heater — plus velo for a left-handed starter — his sidearm release gives it a crummy shape, getting just over nine inches of induced vertical break. The slider is sweeper-shaped with a little depth, but it moves awfully slow for a lateral breaking ball, sitting 79 mph on average. This year, he’s thrown one of those two pitches 90% of the time.

In a video from September of last year, Lance Brozdowski hypothesized that Sale’s ability to defy his stuff grades can be explained to some degree by a distinct mechanical trait: his funky stride direction.

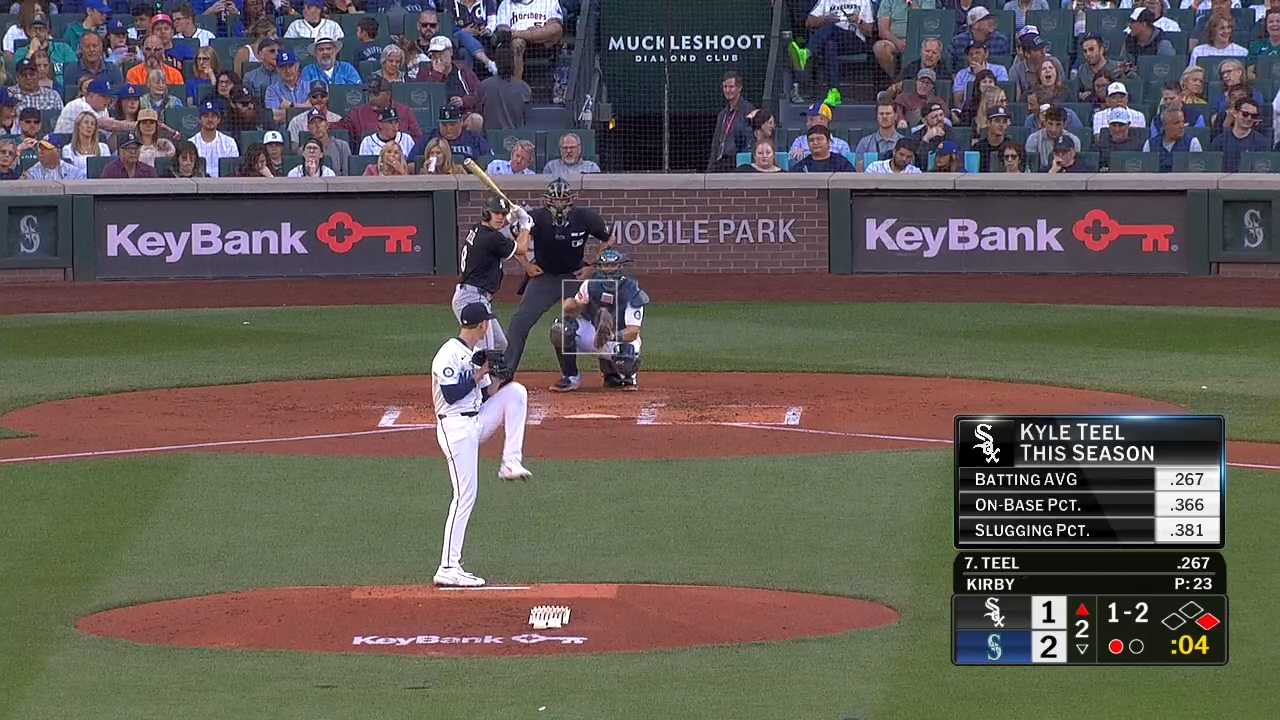

Most pitchers stride in a linear fashion toward home plate. In other words, their plant foot lands directly in front of their starting spot on the rubber. Take George Kirby as an example. Here he is at the start of his delivery, firmly planted on the first base side of the rubber:

And here he is at release, his plant foot more or less straight in front of that starting point:

Sale is not like that. Against right-handed hitters, Sale starts on the third base side; by the time he lands, his plant foot is nearly on the other side of the rubber. This sort of “body deception,” Lance guessed, allows Sale’s stuff to play well above its raw movement characteristics:

If an usual stride direction can turn mediocre stuff into Cy Young results, why doesn’t everyone do it? Lance warns that “coaching this kind of deception into a player is probably impossible.” He suggested that it requires outlier hip mobility to pitch like Sale, and that attempts to do so without the requisite athleticism would likely lead to injury and fatigue.

Given Lopez’s reputation as a prospect, it’s somewhat surprising he qualifies. In his write-up of the trade that brought Lopez to West Sacramento from the Rays last December, Eric Longenhagen wrote that the left-hander is a “below-average athlete.” But his delivery is unquestionably Sale-esque:

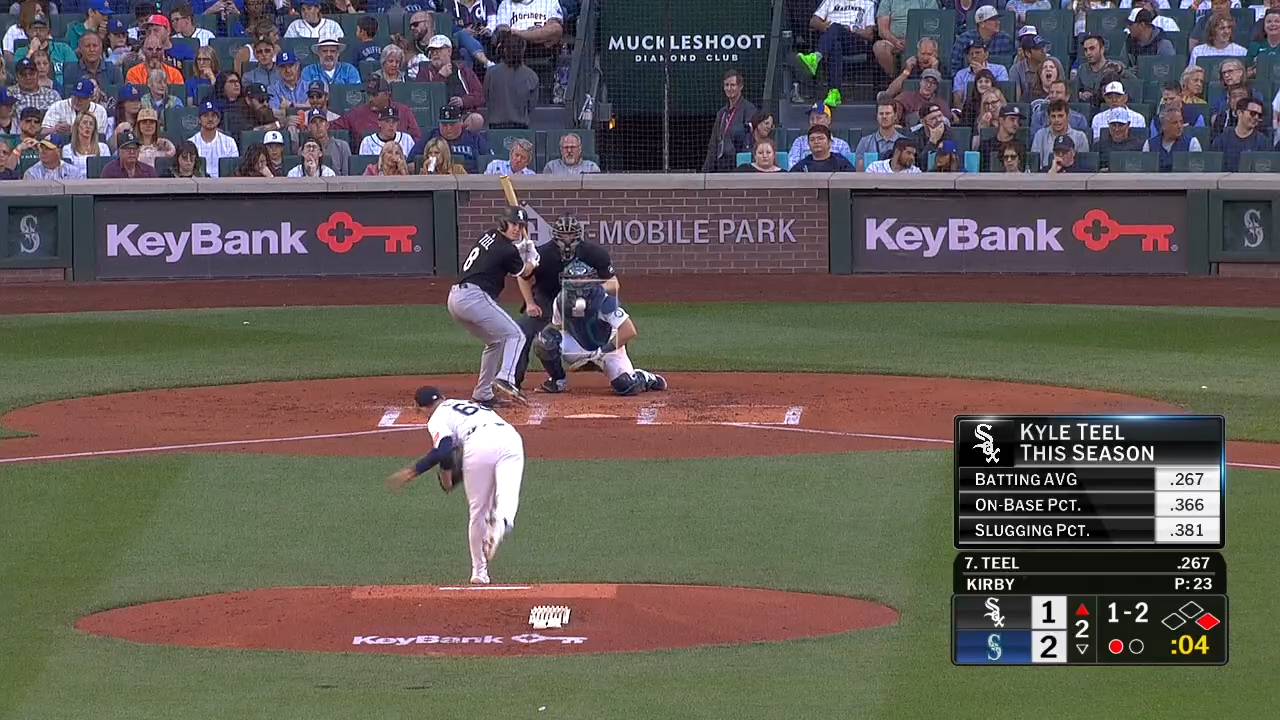

Unlike Sale, Lopez sets up closer to the the center of the rubber:

By the time he lands, Lopez’s plant foot is actually to the outside of the first base side of the rubber:

This bizarre delivery — he also gets to over seven feet of extension down the mound, ranking in the 95th percentile of all pitchers — almost certainly explains some of what’s going on with Lopez this season, because the story doesn’t make sense when told with stuff alone.

Against left-handed hitters, he almost exclusively throws two pitches: that 90.8 mph fastball with sinker-like movement, and a slow, Sale-ish slurve thing. The slurve is at nearly 50% usage, and lefties have done basically nothing with it — they whiff on roughly a third of all swings, and their expected wOBA on contact is down at .247.

Primed with the expectation of the slider, they basically rule out his fastball entirely. That’s allowed the pitch to rack up an absurd 31.5% called strike rate, by far the highest among anyone who has thrown at least 100 four-seam fastballs to lefties. It doesn’t matter if it’s down the middle — they’re just letting it go by:

| Name | No. of Fastballs to LHH | Called Strike % |

|---|---|---|

| Jacob Lopez | 127 | 31.5% |

| Yoshinobu Yamamoto | 409 | 29.3% |

| Kyle Hendricks | 145 | 29.0% |

| Carlos Rodón | 171 | 26.9% |

| Walker Buehler | 260 | 26.2% |

| JP Sears | 102 | 25.5% |

| Dylan Lee | 122 | 25.4% |

| Zac Gallen | 483 | 25.1% |

| Andrés Muñoz | 108 | 25.0% |

| Brandon Woodruff | 112 | 25.0% |

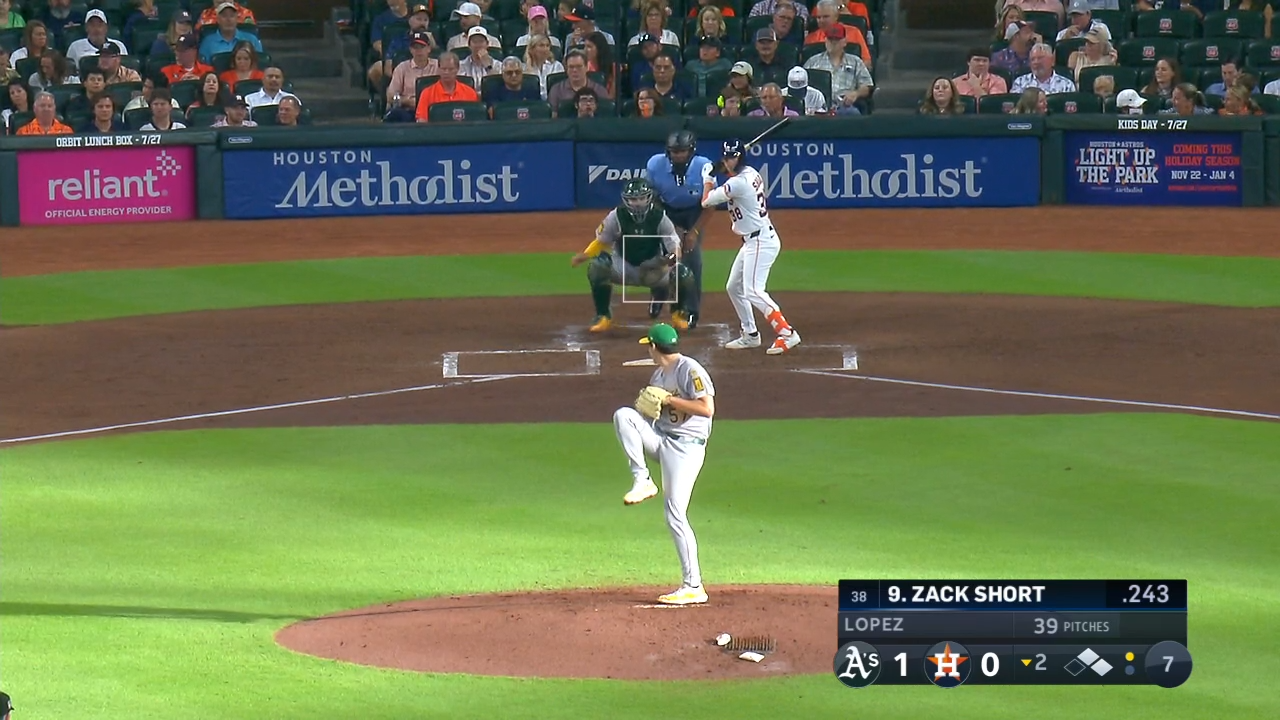

But the vast majority of hitters he faces — over 80% this season — are right-handed. To these opposite-handed foes, Lopez gets a little craftier, mixing in a significant chunk of cutters and changeups.

None of these pitches is clearly the standout, but all four garner above-average outcomes on balls in play and reasonable whiff rates. In early counts, he’s fastball/slider heavy, throwing one of those two pitches nearly 70% (okay, 69%) of the time in 0-0 contexts. To start at-bats, Lopez wants the fastball up and away to righties, while the slider target is back door, aiming for called strikes. These two pitches are also his preferred out pitches — in 0-2 and 1-2 counts to righties, he’s gone with either the fastball or slider over 83% of the time.

It’s the even counts where the changeups and cutters most often appear. Here, they work as bridge pitches, either inducing weak contact when Lopez backs himself into a sticky situation or grabbing a strike to set him up for one of his preferred put-away offerings.

None of this stuff breaks pitch plots or scores bushels of retweets on PitchingNinja. But it’s all been remarkably effective, particularly in recent starts, and it’s hard to explain any of it without referring to the delivery. Lopez’s command isn’t anything special; his approach angles won’t impress any model. He might not keep this up, exactly — between the incandescent streaks, he’s thrown in some stinkers, and perhaps over time, the deception will lose some of its juice — but, at the very least, it seems like he’s much better than anyone considered when he popped up as a throw-in in that December trade.

Deception borne of angular stride direction appears to be a niche interest for the A’s front office. In the same trade that brought Lopez to West Sacramento, they acquired Jeffrey Springs, another soft-tossing left-handed pitcher angling his stride toward the first-base side. Like Lopez, Springs throws what’s charitably termed “junk.” He hasn’t been great this year, but the results, again, are better than what you’d expect given an OOPSY-style projection.

As far as I can tell, competitive advantages are fewer and farther between in today’s game. Everybody’s using the same models, and everybody’s pretty smart in the same ways. Where the competitive advantages exist, they’re relatively marginal. Perhaps with Lopez and Springs, the perpetually underfunded A’s front office has once again found a small edge: pitchers with the ability to overperform their stuff grades by throwing it real weird.

Michael Rosen is a transportation researcher and the author of pitchplots.substack.com. He can be found on Twitter at @bymichaelrosen.

Is this the kind of cross-bodied delivery that the Red Sox top prospects summary was saying is being proactively encouraged/coached in pitchers in their system?