Jhoan Duran and the One True Split-Finger Fastball

PHILADELPHIA — Let’s get one thing clear off the top: A splitter is not a fastball. Any confusion about this topic is understandable, seeing as the full government name of the pitch is “split-finger fastball.” Don’t be a captive to the inflexibility of language. The splitter is lying to you about its very nature.

The origin story of the splitter begins in 1973, when a Cubs minor leaguer named Bruce Sutter was recovering from offseason elbow surgery and struggling to regain his fastball velocity. A pitching instructor named Fred Martin approached the sore-armed 20-year-old with a new pitch. This would be a variation on the familiar forkball, held with index and middle finger spread as far apart as possible in order to impart downward movement.

But while the forkball came out of the hand with an identifiable knuckleball action, Martin had Sutter grip the baseball ever so slightly forward, getting similar action with fastball-like spin.

Sutter was in the Cubs’ major league bullpen within three years, an All-Star in four. He went on to become one of the first great specialized relief aces, winning the NL Cy Young Award in 1979, leading the NL in saves five times, and finishing with 300 saves on the dot.

On the occasion of Sutter’s induction to the Hall of Fame in 2006, Tim Kurkjian commemorated the occasion with a column for ESPN. Kurkjian quoted 16-year big league veteran Gary Matthews, one of Sutter’s most common opponents (they faced off 37 times over 11 seasons), on the pitch Sutter made famous.

Bruce’s ball just disappeared. With his arm motion, and with the movement of the ball, it was really hard to see, like Trevor Hoffman’s changeup… After he threw it, his fastball looked like it was coming 100 mph.

Before Sutter’s career was even over, the splitter had become a fixture across the league. One of its early adopters (and to this day one of its most prolific) was Roger Clemens. Unlike some players of his generation, Clemens has a knack for articulating the finer points of his craft, as you can see in this interview with ur-pitching nerd Rob Friedman on the Pitching Ninja podcast.

Friedman starts by talking about how good Clemens’ splitter was during his second 20-strikeout game in 1996. (Even as a hardcore “ballplayers are better now than ever” guy, I concede that Clemens’ splitter that night was as nasty as anything you’ll see today.)

Clemens’ explanation on how to throw the splitter lasts several minutes, but I want to zero in on one thing he said in particular: “It’s a great pitch, because you’re seeing fat wrist coming at you,” said Clemens, pointing at his wrist to show that he’s not pronating or supinating on release; the splitter looks like a fastball coming out of his hand. “So you think you’re getting 95, but you’re getting 85.”

Not to put too fine a point on it, but that’s a changeup. Yes, the sharp downward and/or lateral movement of a splitter is a big part of what makes it so effective, but sinkers and cutters show different movement from a four-seamer within the same velocity band. Both Matthews and Clemens went to the velocity differential as a key component of what makes a splitter so effective.

At the risk of spending too much time on etymology: Change of velocity equals change of pace equals changeup. It’s been this way since Old Hoss Radbourn was drinking his scotch out of a baby bottle.

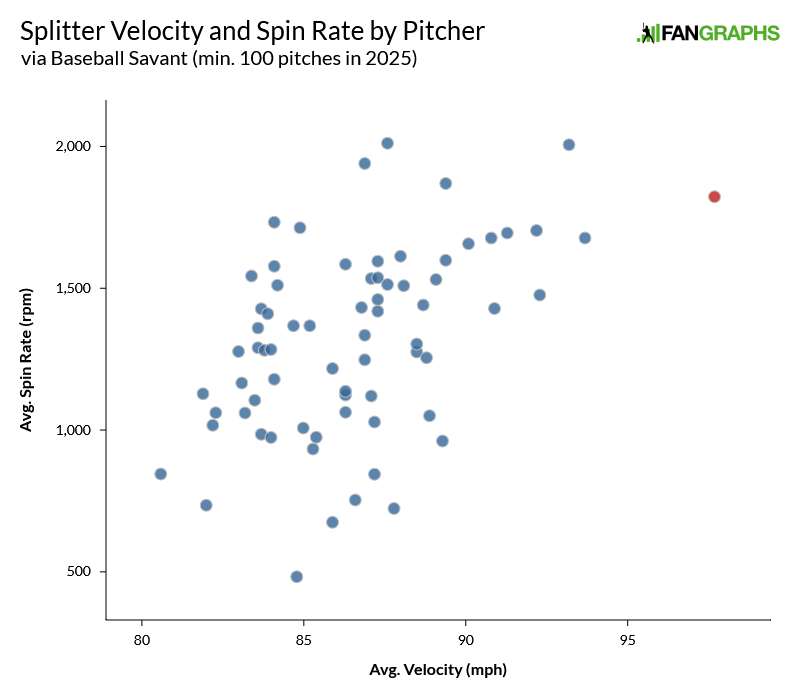

Baseball Savant, MLB’s ultimate public clearinghouse of pitch-level data, thus characterizes the splitter as an offspeed pitch, not a fastball. So far, 71 pitchers have thrown 100 or more of them this year, with many of those coming in with hilariously low spin rates and a huge velocity drop-off compared to the fastball. I’ve made no secret about my love for this pseudo-forkball/splitter/split-change type pitch, as seen in the arsenals of Hurston Waldrep, Logan Gilbert, Kodai Senga, and others. In the age of the 3,000-rpm curveball, it tickles me that a group of sufficiently motivated middle schoolers could get a merry-go-round spinning as fast as Senga’s splitter.

But not all splitters come in this flavor. In case you can’t find the outlier here, I’ve highlighted it in red.

There are a few guys who throw a low-90s splitter that works as a changeup. Paul Skenes and José Soriano, for instance, both throw so hard that 92 or 93 mph is a legitimate step down in velocity from the fastball.

But Phillies closer Jhoan Duran’s splitter averages 97.7 mph. Five times this year, and 39 times total in his major league career, Duran has hit 100 mph with his splitter. That makes him the only person in recorded history to throw a 100-mph offspeed pitch in a major league game.

If you dive deep enough into the FanGraphs archives, you’ll find Eric Longenhagen’s Arizona Diamondbacks’ top prospects list from May 2018. At no. 14 — amidst a bevy of fun names to remember, it must be said — sits a 19-year-old Duran. “Duran’s delivery is silky smooth and he generates big heat, sitting 93-96 and touching 99,” Eric wrote. “His strike-throwing ability and secondary stuff were both better when I saw him this spring, with the slider and changeup each flashing plus.”

Duran’s repertoire at the time was relatively tame, with a slider and an average changeup accompanying his knockout fastball. Two months after that report was published, Duran was traded to the Twins in the Eduardo Escobar deal, and not long after that he had his own Sutter-and-Martin moment while experimenting in a bullpen session.

“I tried to throw a two-seamer,” Duran said last week. “At the time, I had a real splitter, so I moved the ball and tried to mix it up. I moved it a little bit to sink it, so I tried to put something different on it. Almost the same velo, but different movement.”

Just like Sutter, Duran says he knew immediately that he’d found something.

“That day I pitched in the minor leagues for the Twins, I tried it,” Duran said. “I pitched a second time, when I joined a bullpen session, and when I threw it I could see the movement. It’s good, everything, I feel good with that pitch. The next time I threw it in a game, I threw seven innings. I said, ‘That’s my pitch.’ ”

That’s the genesis of the fabled splitter/two-seamer hybrid that made Duran a star within weeks of his big league debut in 2022. The Twins called it a splinker, because everyone loves a portmanteau. But several years passed between Duran’s discovery of his out pitch and his evolution into one of the top closers in baseball.

All relievers are failed starters, the saying goes, but for Duran, the failure to start came extremely late in his minor league career. In parts of seven years in the minors before his first big league call-up, Duran made 80 starts and only two relief appearances.

As a teenager, Duran was listed at 6-foot-5, 175 pounds; someone weighed him since then, and his bio has been updated accordingly to 6-foot-5, 230. On the mound, Duran has the same imposing humongousness as the 6-foot-6, 260-pound Skenes, with a similar easy low-three-quarters delivery.

Skenes was second in the NCAA in innings pitched during his draft year, and is on pace to finish just under the 200-inning mark in his first full go-around in the majors. The similarly hoss-like Duran, who’s made only one IL trip in his entire big league career, could well have made it to the majors in the rotation. Until Duran gave up starting, he was throwing both the splinker and the “real splitter” side by side.

“The splinker was about 92 mph,” Duran said. “I threw the splitter, like, 88-90 on average. It was a good pitch, a really good pitch. But when I went to the bullpen I took it out, because I want everything fast.”

Conventional wisdom says that starters need at least three pitches: A fastball, a breaking ball for same-handed batters, and a changeup for opposite-handed ones. This reflects the long-held axiom that hitters have a harder time with pitches that move away from them. Relievers only face an opponent once per game, and only throw 20 or so pitches per outing, on a good day. They can go all-out on every pitch and get away with only showing opponents one look. Moreover, relievers that do have trouble with opposite-handed hitters can be shielded from bad matchups by a shrewd manager.

Though that hasn’t been a problem for Duran during his career.

| Pitch | Opponent | Pitch% | AVG | OBP | SLG | wOBA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fastball | RHH | 38.9 | .262 | .345 | .379 | .320 |

| Splitter | RHH | 28.2 | .287 | .331 | .433 | .334 |

| Knuckle-Curve | RHH | 28.1 | .158 | .185 | .267 | .197 |

| Fastball | LHH | 46.1 | .232 | .303 | .304 | .275 |

| Splitter | LHH | 28.4 | .196 | .248 | .248 | .225 |

| Knuckle-Curve | LHH | 25.3 | .140 | .208 | .237 | .204 |

Moving to the bullpen also supercharged Duran’s already-impressive raw stuff. Duran loves a stylized set of spikes, and at the foot of his locker there’s a pair of cleats, one of them with the number 104.8 on the heel. That’s the velocity, in mph, of the hardest pitch of Duran’s career. He’s one of only 10 pitchers to hit 104 in the pitch tracking era.

For a pitcher throwing in the upper 90s out of the rotation, a 92-mph splinker might pass as a changeup. But when Duran started going balls-to-the-wall all the time out of the bullpen, that low-90s splitter turned into an upper-90s screamer.

It’s hard to judge Duran’s splitter against like pitches, because there aren’t any. But his splinker averages 13.9 inches of induced horizontal movement, which is top 10 in baseball among splitters that have been thrown at least 100 times. This despite coming in so fast that it doesn’t have time to break that far. For example, Kevin Gausman has one of the best, and hardest-moving, splitters in baseball. But because it averages only 84.9 mph, it’s in the air 14% longer, on average, than Duran’s splinker. That gives it 14% more time to move.

Despite Duran’s wicked movement, he’s not necessarily trying to miss bats with his signature pitch.

“The purpose of the splinker,” he said, “is to get more groundballs. More soft contact.”

Here, he’s succeeding. Duran is 11th out of 353 pitchers on Baseball Savant’s leaderboard in opponent xwOBA, one spot behind Skenes, and 13th in barrels per plate appearance. And while Duran is running strikeout rates in the high 20s, he leads all relievers in groundball rate.

Duran has been in Philadelphia for all of six weeks, and already he’s nearing messianic status among fans who have been unable to fully trust a postseason closer since Mitch Williams crapped the bed 32 years ago. Even last year’s Phillies bullpen, arguably the best and deepest in franchise history, and strengthened by the midseason acquisition of Carlos Estévez, got lit up in the playoffs.

For about 13 months, from late June 2024 to this year’s trade deadline, the Phillies played well on balance but lacked an edge. The Philadelphian propensity to expect the worst led to lingering distrust of high-leverage relievers like Orion Kerkering and Matt Strahm, who have been as good as anyone the Phillies could’ve traded for at the deadline, Duran and Mason Miller notwithstanding.

Over the past decade, the Phillies have had multiple seasons derailed by some truly rotten bullpen performances. Even when their relievers have been good, manager Rob Thomson has favored a more egalitarian, modern approach, going to more generalized stopper roles over favoring a single closer. That got the best out of more versatile relievers like Strahm, Jeff Hoffman, and José Alvarado, and allowed Thomson to pull off a couple tactical masterpieces in the playoffs, but it’s left the ninth inning in the hands of the likes of veterans whose time had largely passed: Corey Knebel, Jordan Romano, and Craig Kimbrel.

Duran is the Phillies’ first set-it-and-forget-it closer since Jonathan Papelbon left the team in 2015, and Papelbon was an unpopular hood ornament on a derelict roster for most of his tenure.

Duran has not been perfect by any means since he joined the Phillies; he’s blown two saves in 16 chances, including one in the division-clincher against the Dodgers on Monday. He took the loss without retiring an out in one of the season’s darkest games, part of the sweep against the Mets at Citi Field last month.

But in his column on the Phillies’ division-clinching win, Matt Gelb of The Athletic identified the arrival of Duran and Harrison Bader from Minnesota as the moment the vibes shifted. The Phillies are 17-2 when Duran pitches, and they have the best record in baseball since they acquired him.

In addition to picking Duran’s brain about his splinker, and whether or not it counted as a fastball or an offspeed pitch, the thing I was most curious about was whether he was aware of the extent to which the fans had latched on to him in just a few weeks.

“For me, it’s an honor to be here,” he said. “As soon as I arrived here, I felt the energy and the love from every person in here. They know me. They want me to be here. I can’t explain to you how excited I am to be here with these fans and the players and the staff — everybody tried to make me comfortable. I love that. I can’t explain it — it’s emotional, you know?”

It’s the furthest thing from empirical to say this, but you could sense the difference in Duran’s last outing before I interviewed him, in a win over the Mets a week ago Monday. Nursing a 1-0 lead in a game that could either reopen the NL East race or close it down for good, Duran left first-pitch splinkers over the plate to both Pete Alonso and Mark Vientos, and quickly found himself with runners on second and third and one out.

With the tying run 90 feet from home and the go-ahead run on second, less than two outs, and the infield in, Duran could no longer rely on weak contact; he had to get Jeff McNeil, a hitter with a 92.2% contact rate this season, to strike out or pop up.

According to Duran, this situation did not bother him.

“I tried to do the same thing [as before.]… Alonso got lucky, because he hit the ball like 60-something mph. It was not a hard groundball,” Duran said. (Alonso’s single was actually 88.5 mph off the bat, but with an xBA of .100, so Duran’s broader point stands, more or less.) “Vientos had a late swing and grabbed the barrel. So I said, ‘I’m good, I need to keep going.’ ”

Duran didn’t go to his splinker once, and McNeil gave him an almighty six-pitch battle. I distinctly remember watching that at-bat thinking one of the two was going to collapse and die right there on the field. McNeil spat on a pair of two-strike curveballs and fouled off two 102-mph fastballs before finally giving up the ghost. The final batter, Francisco Alvarez, whiffed on three knuckle-curves on the exurbs of the strike zone, and in short order, a moment of crisis became a huge win.

Since that outing, Duran has thrown 19 knuckle-curves, averaging 89.6 mph. That’s two mph faster than his seasonal average, which is, on its own, one of the five fastest in the league. He is one of just nine pitchers to throw a 90-mph curveball this year. Duran said it himself; when he moved to the bullpen, he wanted everything to be fast.

Salving the anxieties of an entire fan base, well, it’s a lot to ask of one relief pitcher. But Duran has already shown that he can throw a split-finger fastball that isn’t actually a changeup. If he can do that, anything is possible.

Michael is a writer at FanGraphs. Previously, he was a staff writer at The Ringer and D1Baseball, and his work has appeared at Grantland, Baseball Prospectus, The Atlantic, ESPN.com, and various ill-remembered Phillies blogs. Follow him on Twitter, if you must, @MichaelBaumann.

Duran’s is more extreme, but this reminds me of the utterly bizarre and chimerical “split-finger fastball” that Jeurys Familia threw back in 2015. It went like 95!

That was a nearly unhittable pitch for Familia too bad Alex Gordon was really for the quick pitch splitter he threw him in the World Series.