On Review, the Tie Should Go to the Runner

During the playoffs, when it felt like every game involved at least one close play that everyone would be talking about the next day, I tried my hand at breaking down replays. I captured screen recordings of all the replay angles, dragged them into iMovie, and had a ball figuring out the exact moment when a cleat grazed the plate or a glove caught the runner’s elbow. I’d like to think I even got pretty good at it, so if anybody in the Replay Command Center over on Sixth Avenue ever needs a weekend off, I will gladly cover a shift or two. When you break down footage that way, you learn that close plays happen all the time and they’re so much closer than you realize. I’ve started to believe that we could do a better job of handling the closest of those plays. On tags and force plays, which make up roughly three-quarters of all replay challenges, I think it’s time we change the replay rules so that the tie goes to the runner.

Before we get too deep into my reasoning, we need to start by addressing whether or not the tie goes to the runner according to the current letter of the law. While we all learned that rule as children, it’s not how the game operates at the highest level. As David Wade wrote in The Hardball Times in 2010, umpires don’t believe the tie goes to the runner. They’re taught that there’s no such thing as a tie. Either the runner beat the ball or they didn’t, and that’s that. “There are no ties and there is no rule that says the tie goes to the runner,” said now retired umpire Tim McClelland in a 2007 interview. “But the rule book does say that the runner must beat the ball to first base, and so if he doesn’t beat the ball, then he is out.” That’s a major league umpire declaring that the rules say unambiguously the tie goes to the fielder. While it’s true that the Official Baseball Rules don’t mention ties, the rest of the quote is misleading.

Let’s establish that, logically, whenever a runner touches a base, we can split the time into three distinct categories: before, during, and after. That’s what McClelland was saying. The rule he was referring to was 5.06(a)(1), which leads off the section about what it means to occupy a base. It says: “A runner acquires the right to an unoccupied base when he touches it before he is out.” The onus is on the runner to touch the base first before he’s out. But how does the runner become out?

Rule 5.09 is titled Making an Out. It details the specific conditions under which a runner is either safe or out. In other words, Rule 5.06(a)(1) is dependent on Rule 5.09. And guess what: Rule 5.09 flips things around the other way. Rule 5.09(a)(10) deals with force plays for the batter. It says the batter is out if “he or first base is tagged before he touches first base.” The onus is on the fielder to make the tag first. Rule 5.09(b)(6) deals with force plays for the runner, and it says the same thing: “He or the next base is tagged before he touches the next base.” Garden variety tag plays are covered under Rule 5.09(b)(4). The runner is out when “He is tagged… when off his base.” If the tag comes at the exact same time that the runner reaches the base, well, the runner was tagged while on his base, so he’d be safe.

If these were the only three rules in question, I’d be strongly inclined to say that the rulebook is crystal clear. The tie goes to the runner, because the runner isn’t out unless the tag comes first. That’s what it says in the three simplest, most fundamental rules about what constitutes an out, and those three rules cover the overwhelming majority of safe-out calls on the bases. So while Rule 5.06(a)(1) says the runner occupies the base by touching it before they’re out, that doesn’t matter all that much, because the rules that actually say what constitutes an out put the onus squarely on the fielder to make the tag first.

There’s just one problem: Those aren’t the only three rules that mention timing. I searched the rulebook and found six other befores and afters. They are wildly inconsistent. If a runner misses a base and then tries to return to it, a note in Rule 5.06(b)(3)(D) says the tag has to come first. Onus on the fielder. If the runner steals unnecessarily because it’s ball four, but overruns the base, a comment in Rule 5.06(b)(6) says they have to return before the tag. Onus on the runner. But if the exact same situation happens because the runner misses the base, a note in Rule 5.06(b)(3)(D) says the tag has to come first. Onus on the fielder again. I won’t bore you with the other three, but my point is that once we get into the technicalities, the rulebook isn’t very consistent.

Whatever conclusion you might draw from this mishmash of befores and afters, it’s obvious that the rules don’t come anywhere near saying what McClelland believes they do. A reasonable person could certainly disagree, but my reading leads me to believe that the tie should go to the runner. The three big rules about what constitutes an out would indicate that the tie goes to the runner, while the other six situations deal with technicalities, edge cases that make up such a small percentage of the overall number of safe-out decisions that they may as well be a rounding error.

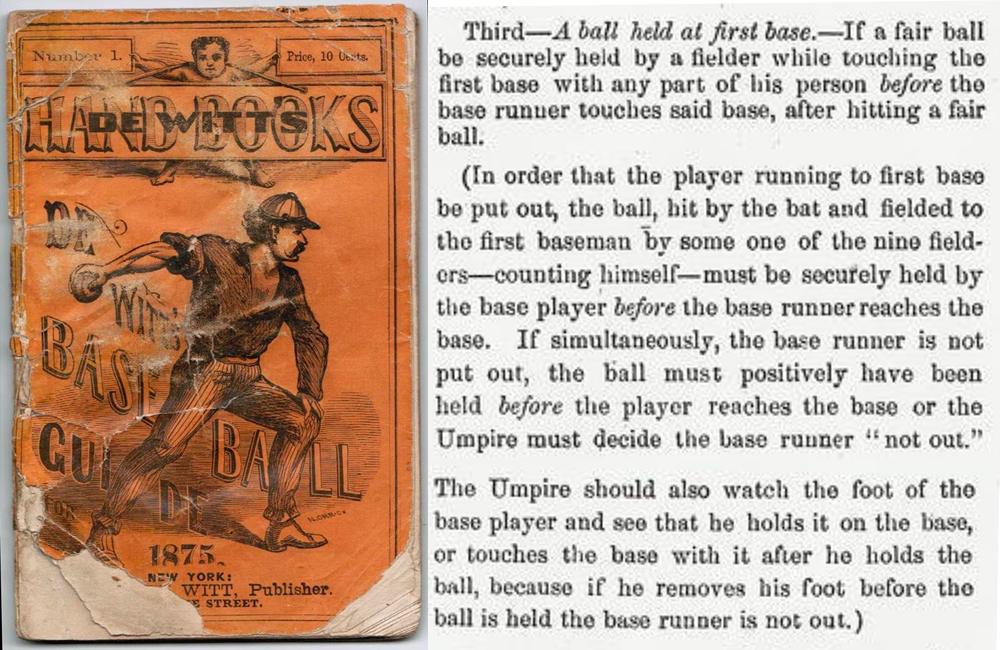

Now, a reasonable person could also argue that this is all just semantics. Maybe the writers of the rulebook just used the words “before” and “after” interchangeably, based on whatever allowed them to write each particular rule in the simplest way possible. The rulebook could have mentioned ties, but omitting them was almost certainly a choice. They make sure to spell out what happens for other edge cases, like balls hitting the foul line and the very edges of the strike zone. Baseball Almanac notes that the 1875 De Witt’s Base Ball Umpire’s Guide, edited by the legendary Henry Chadwick, made it clear that the tie went to the runner. “In order that the player running to first base be put out,” it says in a parenthetical, “the ball…must be securely held by the base player before the base runner reaches the base. If simultaneously, the base runner is not put out, the ball must positively have been held before the player reaches the base or the Umpire must decide the base runner ‘not out.’” Other contemporary sources agreed. John Thorn, MLB’s official historian, told The New York Times in 2012 that the concept was probably never codified in the rules intentionally, because “it gives the umpire something of an out, an excuse if he can call a tie.”

Still, it makes all the sense in the world that umpires are instructed to think that way. They’re on the field in the heat of the moment. They need to be decisive and authoritative. McClelland acknowledged as much. His quote continued: “So you have to make the decision. That’s why umpires are paid the money they are, to make the decision on if he did or if he didn’t.” Acknowledging a tie is essentially an admission of uncertainty, and an uncertain umpire will get eaten alive. As such, umpires are taught a mantra that sounds like it was coined by Eleanor Shellstrop: “When in doubt, bang him out.” Umpires need to project authority, and punching somebody out is more authoritative than calling them safe. That’s why garbage politicians crow about how they’re tough on crime rather than proposing the humane policies that have actually been proven to mitigate crime.

When you’re the one making the call in a stadium full of fans with everything on the line, refusing to acknowledge the existence of ties is completely understandable, maybe even necessary. I’m just not sure why that policy should extend to the removed confines of the Replay Command Center. This interpretation of rules that are vague – deliberately so, if you believe the league’s own historian – could use an update for the challenge era, because if there’s one thing video review has taught us, it’s that ties happen all the time.

Since the introduction of replay in 2014, we’ve seen 15,744 challenges and 7,559 calls overturned, according to Baseball Savant. It just so happens that Rocky Colavito retired with 7,559 career plate appearances, so over the past 12 years, replay has allowed us to fix one entire Colavito’s worth of calls that, with the benefit of slow-motion, were clearly incorrect.

In 2025, just under 52% of challenges ended with the call being overturned, the highest rate ever. For some reason, Savant doesn’t offer a further breakdown of the 48% of calls that were upheld. Sometimes the umpire announces that the video replay has confirmed the call; sometimes they announce that the call merely stands. The latter means that umpire in the replay room couldn’t definitively say within the two-minute time limit whether the call was correct, “due to the lack of clear and convincing evidence.” Fortunately, Close Call Sports has been tracking that particular distinction, and while their numbers are out of date, they’re good enough to give us some general contours. Roughly 20% of calls are confirmed, while 28% merely stand. That is to say that 28% of the time, according to an umpire whose whole job that day is to analyze close calls in the Replay Command Center, using super-slow-motion video from the combined crews of two broadcast teams wielding the fanciest high-speed, hi-res cameras available, it’s still impossible to say for certain whether the runner was safe or out. That sounds an awful lot like a tie to me! At this point, I will avoid the temptation to make a detour into Zeno’s paradoxes or infinite set theory and simply acknowledge that were it possible for us to set our cameras to an infinitely high frame rate, we would always be able to tell which thing happened before which. But that’s never going to happen.

Once you’ve drunk deeply from the well of super-slow-motion replays, you realize that some plays really are impossible to call with certainty. The bodies of the players involved often block what would otherwise be the best view of the tag. As it nears the bag, the runner’s hand or cleat usually kicks up a wave of dirt ahead of it. This wave obscures the base, making it hard to tell exactly when contact occurs. It’s even harder at home plate, where the hand or cleat doesn’t run into a solid base, but simply glides across the top of the plate. Because most cameras are stationed at somewhat elevated positions, and most tags are made with the fielder catching the ball high and then sweeping downward to make the tag, the back side of the glove usually blocks the view of the precise moment when the front side actually touches the runner. If we were to outfit each base with an array of 2,000-frame-per-second Edgertronic cameras at various strategically-selected angles, we could surely cut that 28% figure down significantly, but I doubt we’d ever approach zero. We will always see plays that are, for all intents and purposes, ties:

It’s one thing for umpires on the field to pretend ties don’t exist in order to carry out their duties without compunction. It’s another to make that same assertion when you’re analyzing footage that slices each second into a minimum of 29.97 frames and you still can’t tell what happened more than a quarter of the time. At that point, you’re living in denial. Ties are real. They happen roughly 400 times a season, and roughly 300 of those are on forces and tag plays. That’s a couple times a night.

When Major League Baseball adopted expanded instant replay in 2014, it essentially adopted the model that the NFL has been using since 1999. When the play is too close to call, it defaults to the original call on the field. It’s understandable. Nobody wants to undermine the umpires. Their job is tough enough already. It makes sense to reinforce their authority by implying that when in doubt, their view is the right one. It also represents the smallest departure from the way the game worked before replay, which was a priority back when expanded replay was introduced. “We’re really [targeting] the dramatic miss, not all misses” said Tony La Russa, who served on the committee that established the system. But if your goal is getting calls right, you could argue that this is the worst way to handle plays that are too close to call.

First, even if the umpire in New York can’t say for certain what happened, spending a couple minutes analyzing the best footage available will always give them a better idea of what happened than the umpire who got one crack at it in real time. It’s just impossible that it wouldn’t. Accuracy would no doubt be vastly improved if the replay umpire got the final say, no matter what their degree of certainty, using their best judgment just like the umpire on the field.

Now let’s go back to the 72% of challenges that are settled definitively by the replay umpire — that’s the 52% of calls that are overturned plus the 20% that confirmed. We’re setting aside the 28% that are too close to call. A little arithmetic tells you that of this subset, the initial call on the field was right 28% of the time and wrong 72% of the time. I realize this is confusing because the percentages happen to be the same, but what this means is that when the replays are clear enough that the umpire in New York can make a definitive call, they’re clear in one particular direction: the umpire is wrong nearly three-quarters of the time. And once again, those are the plays that aren’t quite as close! Why exactly are we deferring to the umpire on the field on plays that are even closer? Because that’s how the NFL does it? To spare their feelings? That last issue actually is spelled out very clearly in the rulebook: “Umpire dignity is important but never as important as ‘being right.’” Logic says that if umpires are wrong 72% of the time on the challenged calls that are clear enough to be definitive on video, they probably fare even worse on the plays that are too close to call. The most accurate way to handle them might be just to reverse the call on the field as a matter of policy! Even flipping a coin would surely be much more accurate.

Those are obviously capricious suggestions. I don’t mean to denigrate the umpires in any way. They have an extraordinarily difficult job, and just like the players on the field, they’re the best in the world at what they do. But it’s obvious that there’s a certain subset of plays that really are too close to call, even when we push past the limits of human physiology and resort to the most advanced technology available. And on the slightly-less-close calls, the record of the umpires on the field isn’t sterling, quite possibly because when the play is close, they’ve been taught to just call the runner out by default. That itself is one argument in favor of giving the tie to the runner when the replay is too close. When umpires aren’t sure, they bang the runner out, which means that on the very closest of plays, many of them ties that arguably should be going to the runner, they’re a little bit biased in the other direction. If you want proof of that, look no further than the fact that in 2025, 70% of the challenges on close plays at first base were overturned! If the previous percentages hold, that means that the call on the field was only confirmed around 13% of the time!

Deciding these ties in favor of the runner would also push the game in the direction the league wants anyway. Each year, it would turn a few hundred out calls into safe calls, boosting offense slightly without furthering the boom-and-bust cycle of home runs and strikeouts. It would also provide a slight reprieve from the low-BABIP doldrums, instantly adding roughly two points to the league rate. The downstream effects would encourage the exciting parts of the game that everyone wants to see more of: putting the ball in play, stealing, and taking the extra base. Maybe those effects would be too small for us to notice on a daily basis – these ties would only crop up once every eight games – but they would be real and measurable.

Defaulting to the judgment of the umpire on the field on even tougher plays makes plenty of sense from a human perspective. It helped ease the game into the era of expanded replay without upsetting the existing norms too much. But purely in terms of getting the correct call, it’s probably the worst option available, and it involves the denial of a reality that we can all see: ties happen a lot.

We’re now 12 years and several rule tweaks into expended replay. Why not keep improving it? The league has updated and clarified the rules of the replay system multiple times. It’s banned the shift, enlarged the bases, implemented the pitch clock, and limited pickoff attempts. It’s implementing an ABS challenge system for balls and strikes this year. I think it’s fair to say that Major League Baseball is no longer just concerned about the dramatic miss.

Lastly, I can’t deny that having the game conform to what we were all taught as kids has informed my opinion. The tie would finally go to the runner, and that would feel right. To that end, I would note that it’s not just fans who believe the tie goes to the runner. Watch a few challenges and I guarantee that you’ll hear one of the broadcasters mention it as a matter of course. The play-by-play people have spent their entire careers calling baseball. Nearly all of the color commentators are former players who have spent their entire lives in and around the game. They have producers and researchers in their ear. And they believe that the tie goes to the runner! It’s quite possible that the umpires – along with the true sickos, of course – are the only ones on the other side of this argument. So while this may feel like a dramatic shift, it would also just bring the rules into alignment with how nearly all of us, both inside and outside the game, already understand them to work.

Davy Andrews is a Brooklyn-based musician and a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @davyandrewsdavy.bsky.social.

I have no comment other than to say this was a wonderful article. Thank you, Davy. This is the latest example of why your articles are must reads to me.

And possibly the most important article he has written for Fangraphs.