Six Innings of Zeroes, Followed by Seven At-Bats of Mayhem: Dodgers on Verge of Sweep

PHILADELPHIA – If the lesson to learn from Game 1 of the NLDS is that nobody’s perfect, the lesson to learn from Game 2 is that some pitchers come close. Blake Snell and Jesús Luzardo delivered the kind of pitchers’ duel to warm the hearts of dyspeptic ex-pros who should have to drop a quarter in the swear jar whenever they start a sentence with, “Back in my day…” Snell allowed only a single hit against four walks and nine strikeouts in six innings of work; Luzardo, after a tricky first inning, recorded 17 straight outs.

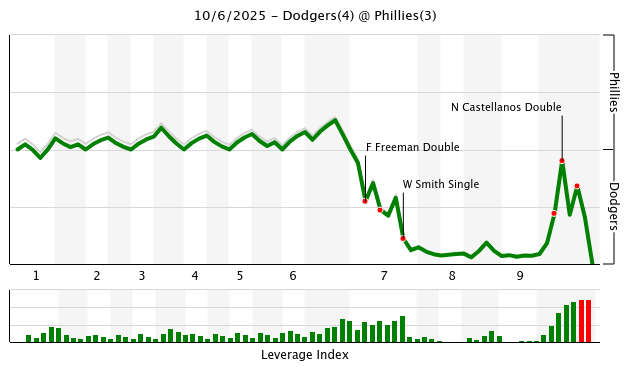

After watching a blank scoreboard for the first two-thirds of the game, both teams cracked under the strain in the endgame. The two clubs followed this pair of near-perfect pitching performances with a manifestly imperfect bottom of the ninth, as both teams committed blunders in tactics and execution that threw a settled game into chaos.

The final score: Dodgers 4, Phillies 3. In this heavyweight bout, the Dodgers are one win away from a knockout victory.

With one out in the first, Luzardo allowed a single to Mookie Betts, walked Teoscar Hernández, and nearly surrendered an RBI double to Freddie Freeman. But Nick Castellanos, with some effort, tracked it down, and Luzardo was able to escape without damage.

Luzardo, more than most pitchers in the league — certainly more than any other good starting pitcher — does his best work with the bases clear. His opponent wOBA climbs 96 points when there’s even one runner on, the eighth-biggest increase out of the 275 pitchers who threw at least 1,000 pitches this season.

The bespectacled left-hander underperformed his FIP by more than a run this year, the fifth-biggest discrepancy of any qualified starter this year. That made Luzardo’s six-place finish on our WAR leaderboard a notable curiosity; how could one of the league’s elite strikeout-generating starters, with a better-than-average home run rate, end up with an ERA barely a quarter of a run better than league average?

Well, FIP doesn’t take clustering into account, and the real world does, and when things went bad for Luzardo this year, they went really bad. He allowed 80 earned runs in the regular season this year; fully a quarter of those came in a two-start stretch around Memorial Day. Included in that run is an eight-run fourth inning against the Brewers; that single inning accounted for 10% of the scoring off Luzardo all year.

It was, therefore, of paramount importance that he keep the bases clear. And after squirming out of that first-inning conundrum, he did. From the first through the end of the sixth, Luzardo set down 17 straight Dodgers. This was the 15th anniversary of Roy Halladay’s playoff no-hitter, an occasion the Phillies commemorated by having Halladay’s son Braeden throw the ceremonial first pitch to Carlos Ruiz. During that no-hitter, Halladay never set down that many consecutive batters.

In his penultimate regular-season start, Snell kept the Phillies off the board over seven innings, striking out 12, walking two, and allowing only two hits. He picked up where he left off, holding the Phillies hitless until there were two outs in the bottom of the fifth.

This is not a matchup devoid of power. Seven of the 18 starting position players in this game have at least one 30-homer season in their careers. Two others, the Maxes Muncy and Kepler, came off the bench. That includes Kyle Schwarber and Shohei Ohtani, the National League’s two leading home run hitters this season.

But from the second through the sixth innings, only two balls came off the bat at more than 90.3 mph, and both went for groundball outs. There was a funny moment in the bottom of the fifth where J.T. Realmuto poked the most routine fly ball you’ve ever seen to right field — it came off the bat at 87.5 mph and traveled only 314 feet — but the crowd jolted to life like it was the hardest-hit ball they’d ever seen.

In fairness, by the standards of the day, it was absolutely torched.

But here’s the thing about Snell: He doesn’t throw strikes. Out of 219 pitchers who have thrown 200 or more innings out of the rotation in the 2020s, Snell has the second-lowest in-zone rate. Blessed with mid-90s heat from the left side, two good breaking balls, and a terrific changeup, Snell skirts the fringes of the zone and invites opponents to chase. At times, he flails around, but when he’s on, it’s stop-hitting-yourself stuff.

One of the keys to this series has been the Dodgers’ ability to suffocate the top three hitters in the Phillies’ order: Trea Turner, Schwarber, and Bryce Harper. Between Game 1 and the first two trips through the order in Game 2, they were a cumulative 1-for-16 with two walks, the lone hit a seeing-eye single from Harper on Saturday night.

When these three are rolling, the Phillies can score runs in piles. And it’s clear that they were trying their best — Harper and Schwarber ripped off some space-time-tearing swings early in the game. But in Snell’s six innings of work, he only gave these three hitters one good pitch to hit: A letters-high four-seamer to Turner, the very first pitch he threw all night.

By the sixth inning, these guys had mostly figured out the game. Snell threw the Phillies’ first four hitters 20 pitches; only two of them were in the zone. Turner walked with one out, and even though everyone in the park knew what was coming, stole second. Schwarber, who’s having a brutal series, drew a walk of his own.

But Harper struck out on six pitches, and Alec Bohm slammed a changeup in the dirt down the line to third — this was one of the two hard-hit grounders in the middle five innings. Miguel Rojas fielded it cleanly with his momentum going toward the bag, but he chose not to throw across the diamond to get Bohm, who runs like a front-end loader. Instead, he raced Turner — literally the fastest player in the league this year, according to Statcast — to the third base bag. It was more exciting than it needed to be, but it ended the inning all the same.

Even in the moment, you could tell that the Phillies would be lucky to get another chance this good before the Dodgers’ offense woke up. Sure enough, the first batter Luzardo faced, Teoscar Hernández, rang a single straight up the middle. Freeman followed by dumping a ball into the right field corner, and Castellanos took so long to return the ball to the infield that Freeman — who runs like Bohm, but carrying a heavy parcel in each arm — was able to hustle out a double.

In came Orion Kerkering, who, like Matt Strahm the night before, had been given an unfairly difficult task: Get out of a two-on, no-out jam without allowing a run. Like Strahm, he came pretty close. Enrique Hernández opened the scoring with an infield single right at Turner, whose throw to the plate was just fractionally late. A replay review showed as close as play as you’ll find — through highly motivated reasoning, one could argue that Teoscar’s foot wasn’t quite on the plate when Realmuto’s glove hit his leg — but there was no remotely plausible basis for overturning the call.

After that, the Dodgers’ offense — held in a constricted, almost constipated state by Luzardo to that point — let loose. Back-to-back two-out singles from Will Smith and Ohtani gave the Dodgers four runs’ worth of breathing room.

It came in handy; Kepler, who certainly came to play this week, tripled and scored in the eighth. For a moment, the tying run was on deck, and it got so loud that Emmet Sheehan couldn’t hear his PitchCom. But once again, Schwarber and Harper went down meekly.

Entering the bottom of the ninth, this had been a closer game than even a 4-1 score would indicate. The decisive plays in the bottom of the sixth and top of the seventh were decided by, cumulatively, about a dozen pixels on a replay screen.

But that wasn’t close enough for Dodgers manager Dave Roberts. In the Phillies’ two wins at Dodger Stadium last month, they scored a single measly run in 5 2/3 innings off bulk reliever Sheehan, who came in after Anthony Banda opened the series. The following night, they didn’t even get a hit off Ohtani in five innings.

But the Dodgers bullpen surrendered 13 runs (plus one inherited runner) in eight innings in those two games. That included a ninth-inning meltdown from longtime relief ace Blake Treinen, who went 1-5 with a 9.64 ERA in 12 September appearances.

Two nights earlier, Roki Sasaki had beat the crap out of the Phillies, with his splitter so dominant that Jeff Passan wrote a feature about it. Turning a recently injured rookie starter into an everyday closer is a tricky business, but with the off day on Sunday, surely Sasaki would be available.

Roberts went with Treinen instead. The Dodgers had three runs to play with; how badly could it go?

Bohm led off with a single up the middle. Then Realmuto doubled — the Phillies’ hardest-hit ball of the night — to bring the tying run to the plate. Castellanos, who’d been astonishingly poor on both sides of the ball to this point in the series, paddled a soft liner to left and dodged the tag at second for a two-run double.

Out went Treinen, and in came left-hander Alex Vesia, who’d cauterized the Phillies’ eighth-inning rally in Game 1. This put Phillies manager Rob Thomson in a bind. He’d already configured the bottom of his lineup for right-handed pitching, leaving three lefties with big platoon splits — Bryson Stott, Brandon Marsh, and Kepler — lined up for Vesia like empty beer cans on a fence rail.

The advantages of having a runner on third with one out being what they are, Thomson ordered Stott to bunt.

Oh boy. Thomson has profited greatly during his four-year tenure by being a hands-off manager, which is the right approach for a veteran team that’s been long on power and short on athleticism for most of that time. The Phillies only laid down 16 sacrifices all year, four of them by Johan Rojas, who doesn’t generate much more exit velo when he swings from his heels. Too-clever-by-half bullpen management for Roberts is him playing the hits. Too-clever-by-half small ball is jarringly out of character for Thomson.

“Just left on left, trying to tie the score,” Thomson explained after the game. “I liked where our bullpen was at … as compared to theirs. We play for the tie at home.” Pressed on the issue, he continued: “Mookie did a great job of disguising the wheel play. We teach our guys that if you see wheel, just pull it back and slash because you’ve got all kinds of room in the middle. But Mookie broke so late that it was tough for Stotty to pick it up.”

No doubt Muncy and Betts executed the wheel play to perfection. Stott’s bunt was hit harder than would’ve been ideal, but I’ve seen worse. But Stott squared and pulled back on the first pitch, and the wheel play was on then too.

“You don’t want to hit the ball to first because the first baseman is three inches from you, and you don’t want to hit it to the pitcher,” Stott explained. “The first baseman has an easier play going to third, so you want to bunt it to the third baseman.”

Maybe. Vesia, a left-handed pitcher, is coming off the mound to the third-base side, and while I’d bet on Freeman to make the throw to third, Stott could’ve pushed the ball past him as he was charging. Or he could’ve swung away.

As much as I disagree with Thomson’s conclusion, I see his logic. Stott has a galactically huge platoon split: 61 wRC+ against lefties, 111 against righties. There’s a reason he didn’t start against Snell, and the odds of him hitting a walkoff homer were vanishingly slim. But Stott puts the ball in play well even against lefties: His strikeout rate is 17.9% and his contact rate is 79.9%. The odds of him advancing Castellanos with a productive out aren’t terrible even if he swings away. Asked about this possibility, Stott toed the party line.

“Obviously, we’re in the postseason, and we’re trying to win games, and getting the tying run on third with less than two outs is big,” Stott said. “It opens up a lot of stuff.”

A successful bunt probably doesn’t draw too much notice, but Stott got a little too much of it, the Dodgers played it perfectly, and Castellanos took forever to get to third base. When everything settled, the Phillies were down a base and an out, and the Dodgers had room to breathe.

Harrison Bader followed with a ringing pinch-hit single, demonstrating why the Phillies had missed him so badly in the starting lineup. He also demonstrated why he couldn’t start, lugging his bum groin up the line like a millstone. This was the only circumstance in which Weston Wilson would pinch-run for Bader with the game on the line.

Thomson had to burn Wilson to pinch run — unless one of the Phillies’ starting pitchers ran track in high school, the only other option was backup catcher Rafael Marchán. But that forced Kepler to hit against a lefty, and Vesia got him to ground into a fielder’s choice thanks to some more terrific defense from Freeman.

But the Phillies, by now, had finally gotten the tying run to third base with the top of the lineup coming up. Apparently Sasaki was available after all.

“He hasn’t gone two out of three much at all… So I didn’t want to just preemptively put him in there,” Roberts said. “I felt good with who we had, with a couple of our highest-leverage relievers. And fortunately he was ready when called upon. I liked him versus Trea, and he got a big out for us.”

Sasaki needed two pitches. Splitter inside for ball one, then a 99-mph four-seamer Turner couldn’t get the bat around on. Weak grounder to second. Ballgame.

The Phillies have held Ohtani and Betts in check offensively. Their starting pitching has been absolutely outstanding. Their high-leverage relievers — Kerkering, Strahm, and Jhoan Duran — haven’t been perfect, but they’ve been placed in some tough positions. Insofar as they’ve been vulnerable, this is nowhere near the all-out relief meltdowns that sank the Phillies in 2023 and 2024. On Saturday, they put the tying run in scoring position in the eighth inning. On Monday, they put the winning run on base with one out in the ninth.

That one fatal weakness the Dodgers have, the one the Phillies exploited so relentlessly in the regular season? It’s still there, and they did as much as they could with it. Dodger “relievers,” as in full-time bullpen arms, have produced an opponent batting line of .571/.571/1.143. They’ve allowed three extra-base hits and only recorded three outs.

But Harper and Schwarber — in previous years, the only two Phillies hitters you could count on in October come what may — have done almost nothing. They lost their starting center fielder to injury, made a couple questionable managerial moves, and ended up on the wrong side of a couple bang-bang plays.

Against some teams, that’s survivable. But against the Dodgers, the standards are higher.

Michael is a writer at FanGraphs. Previously, he was a staff writer at The Ringer and D1Baseball, and his work has appeared at Grantland, Baseball Prospectus, The Atlantic, ESPN.com, and various ill-remembered Phillies blogs. Follow him on Twitter, if you must, @MichaelBaumann.

I was surprised Treinen even made the roster

I know there are the ghosts of playoffs past, but Kershaw has to have been a better option, right?

They could have just stayed with Sheehan

I meant for the roster spot, but yes.

Edit: brainfart, missed that Kershaw was added to the NLDS roster.

If Roberts were going to bring in a lefty then it would have been Vesia. Kershaw is likely gonna be used as a long reliever earlier in the game or break glass in case of emergency option.

And by that I mean there is literally no one else who can pitch and it’s a clinch/elimination game.

Ok so I’m obviously aware of the fact that a) Sheehan absolutely could have finished the game and b) Treinen’s regular season sample size is much more significant but Treinen literally just faced 4 batters in the Wild Card series and struck out 2 of them allowing just one hit.

I would have stuck with Sheehan personally but I don’t think the move to bring Treinen in was nearly as disastrous as so many people seem to think it was.

I agree. I’m often the first to complain about Roberts’s bullpen management but I don’t think it was an indefensible choice. Sheehan had already gotten through the meat of the order and starting the 9th looked, on paper, like a good opportunity for a lower-leverage guy.

Yup. It was to face three righties who wouldn’t be pinch-hit for, with at least the 3-run cushion. Was about as favorable a situation as possible. And the playoffs are long, and there’s a real advantage to any night they could’ve rested Sasaki.

Even as is — BECAUSE they escaped with the win anyway — it was pretty valuable. The question was, did Treinen only look decent against the Reds because their offense is utter ass (as he looked decent against them when they faced off in his two late August appearances). Now, they know. Treinen can’t be used in leverage (for anything but MAYBE a favorable righty-righty matchup with 2 outs) for the rest of the playoffs. Hopefully, that’s the end of it, and the plan for “how to end games when it’d really be best to let Sasaki sit” has to be rewritten in some new, creative way.