The Giants and the Anti-Shift

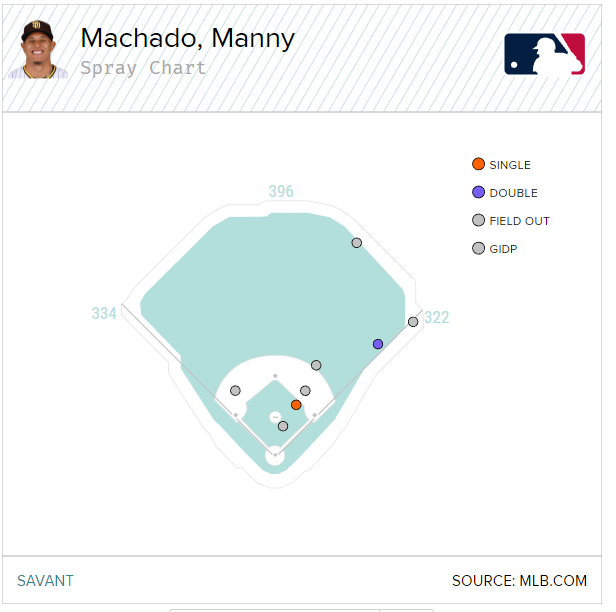

Here’s a spray chart of Manny Machado’s groundballs this year:

And here’s a heat map of all of the grounders he’s hit in his career:

Oh, hi there. Don’t worry, you haven’t inadvertently stepped into a list of every player’s batted ball tendencies. Part of writing is building a sense of mystery. I’m just setting you up for a payoff later on. Whoops, gave that one away too easily! In any case, let’s move on.

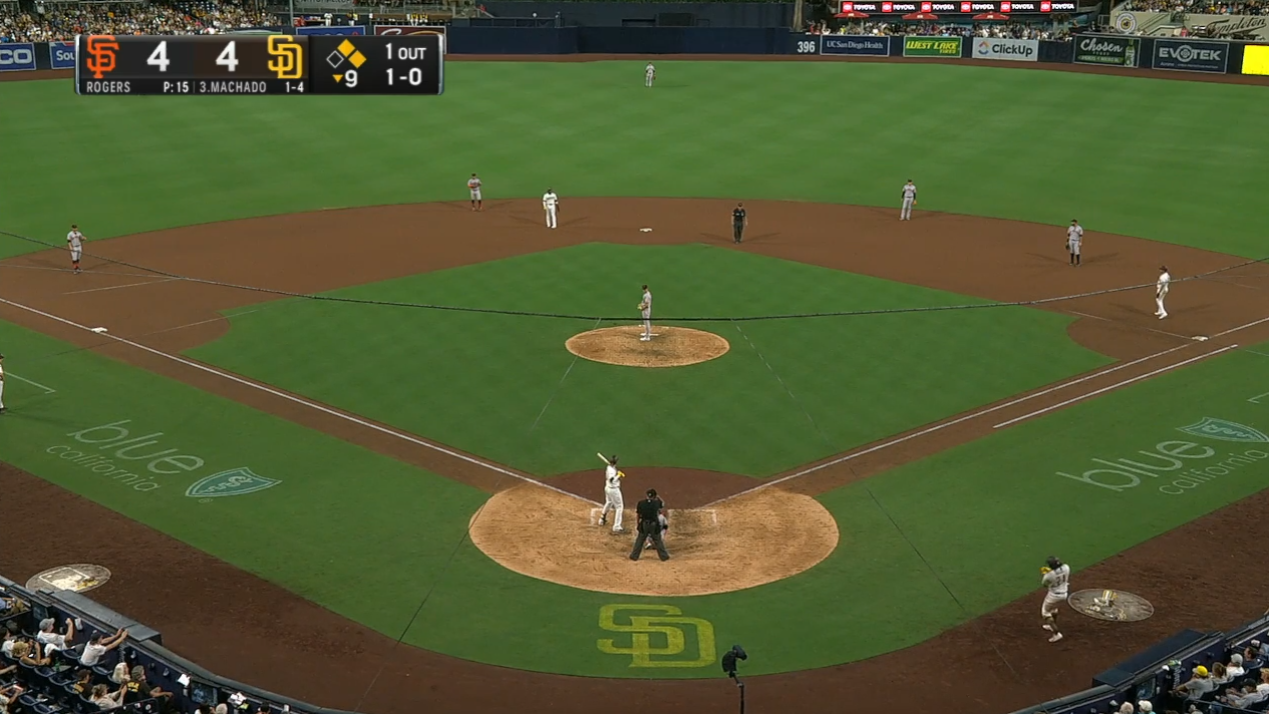

Take a look at this double play from the first inning of Tuesday night’s Padres/Giants game:

You have to read between the lines a bit, because the broadcast never showed the alignment of the defense, but you can see second baseman Thairo Estrada moving from a position near second base, while Brandon Crawford’s positioning as he approaches second base to turn the double play implies he was coming from roughly a standard shortstop position.

Here’s an overhead shot of San Francisco’s defense in the fourth inning, when Machado came to the plate with the bases empty:

Again, I’m operating on inference, but aside from Brandon Belt playing off the line at first with no runner to hold, this looks like the exact same defense the Giants played earlier. That’s a reasonable alignment, and in fact, the Giants play it a lot. Per Baseball Savant, they shift only 18% of the time against right-handed batters. With no runners on base, here’s their standard un-shifted positioning:

For the record, when they shift, it basically involves rolling the second baseman over the bag, which scrunches in the shortstop and third baseman, but the two formations are reasonably close. Generally speaking, the Giants like to play their second baseman up the middle and their shortstop in what I’d term a classic shortstop position. This is an area of strength for the team; they were the best team in baseball at limiting righty production when they shifted last year, and they’re in the top 10 this year despite a leaky defense.

Here’s an action shot of the San Francisco defense reacting to a Machado line drive in the sixth inning of Tuesday night’s game:

It’s not perfect – there are no broadcast shots of the defense because Machado put the first pitch of the plate appearance into play – but it appears to be the same defense as before, perhaps with a slight adjustment for the runner on second.

Here are the Giants, getting ready for play as Machado leads off the eighth inning:

Sure, the inning hasn’t actually started yet, but all four infielders came set in those positions, which makes me think they’ll end up staying there. They pretty much always do, after all, and it makes sense when you look at Machado’s spray chart.

Why am I harping on this so much? Why did I make you read 500 words about the Giants setting up in completely normal locations against a right-handed batter with unremarkable batted-ball tendencies? Hold onto your butts, because here’s how the Giants positioned themselves against Machado in the ninth inning, with one out and the game on the line:

That’s… that’s a lefty batter’s shift. Not an extreme one, and there are parts of it that don’t make much sense, but the shortstop is closer to the second base bag than the second baseman, which was clearly not the case every previous time Machado had come to the plate. What the heck?

One thing is clear: this wasn’t an accident, a misreading of defensive signals. The Giants were in this alignment before the first pitch, and they stayed with it for the duration of the plate appearance. It isn’t about the runners, either; as we saw in the sixth inning, the second baseman can handle holding the runner on quite easily from his “normal” spot in the San Francisco alignment.

So what’s going on here? The Giants devour data and let it guide them to their decisions. They aren’t sticking their heads in the sand and doing what worked 20 years ago – and even if they were, this probably wouldn’t have been the call 20 years ago either. Can we see what they saw?

Here’s a hint. Coming into last night, Machado had put eight balls into play against Tyler Rogers, the righty submariner on the mound for San Francisco last night. Here are the locations of those eight:

Oh. Neat. It’s even more extreme than that, because here’s the one ball he hit to the pull side:

For whatever reason, Machado just couldn’t pull the ball against Rogers. I went back and watched each of his foul balls for good measure. He yanked one foul to the pull side, but mostly hit them on the ground or in the air into the right field bleachers. It wasn’t a pitch location issue – Rogers has come inside plenty against Machado. For whatever reason, Machado just seemed to stay back on Rogers’ pitches and take them inside out, or at least, he had in their limited encounters prior to last night.

This is weird! It would be one thing if righties as a whole peppered the opposite side of the infield against Rogers; he’s a unique pitcher, with a release point and pitch movement unlike anyone else’s in the game. Could he be inducing opposite-side grounders against righties at an extreme rate? Eh, not really. If you want the math, here it is separated into three groups: pull, straightaway, and opposite:

| Pitcher | Pull | Straightaway | Opposite |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rogers | 35.2% | 45.1% | 19.8% |

| RHP Overall | 47.8% | 35.1% | 14.3% |

Rogers gets more opposite-side grounders than your average righty and fewer pulled ones, but the Giants’ “standard” alignment against righties works pretty well against that; putting the second baseman near second base puts three defenders right in the hot zone.

The Giants have been doing a lesser version of this shift with Rogers for a while now. Here’s the infield before his first pitch to Ramón Laureano in a game on August 6:

That’s more straight-up than reverse shift, and it makes plenty of sense to me. It’s a compromise between their normal positioning with a righty at the plate and what they showed last night; both the shortstop and the second baseman essentially move five feet towards the first base side from where they usually stand. Here it is graphically:

That’s not quite the Machado shift, but you can see the rough contours of it. The plays captured there – a runner on either second or third (you can’t split it smaller than that thanks to sample size issues), Rogers on the mound, righty at the plate – show you what the Giants want to do behind Rogers against an average righty.

I don’t quite buy that Machado is anything other than an average righty when it comes to batted ball distribution. In his career, he runs a league average pull rate on grounders against righty pitchers. He gets shifted less than an average righty, but not by much; in 2021 and ’22 combined, he’s seen shifts on 16.8% of pitches from righties, as compared to 18.6% for all righty batters combined. In other words, he’s pretty close to neutral there.

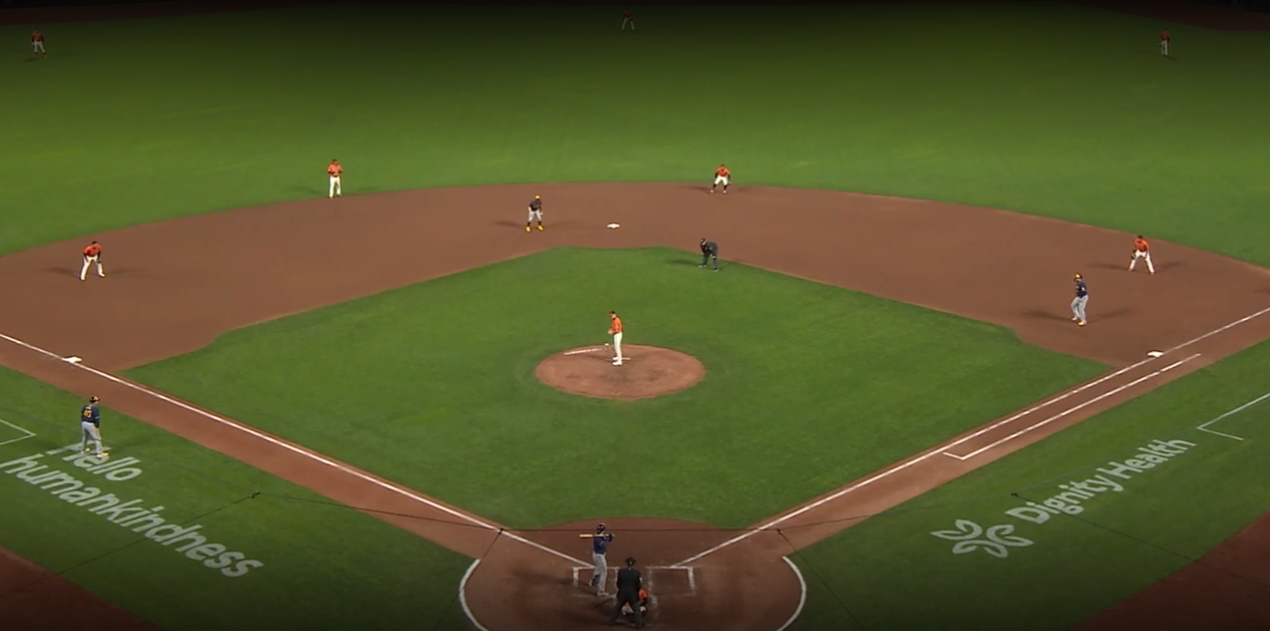

Just for a sanity check, I found a few other first-and-second situations Rogers pitched in from earlier this year. They mostly look like this one, from a July 15 tilt against the Brewers:

You might notice that the second baseman is in the middle of moving; he bluffed a pickoff move before retreating two steps to the outfield grass. The key here is that this positioning looks, more or less, like the team’s normal alignment, with a tiny shift towards first.

Why did they over-play Machado to go the other way? Did his limited history with Rogers influence the decision-making? We’ll probably never know. It struck me as strange while watching it, though, and it was notable enough that the Giants announcers noticed, too. (As an aside, the Giants broadcast does an impeccable job of displaying shifts, which helped greatly when writing this article.)

So, did the Giants’ precise positioning matter? Did their next-level thinking get them ahead, or alternately cost them the game thanks to Machado hitting it to the weakened pull side? In a word, no:

That’s baseball for you. You can try to pick up small edges with shifts and tendencies all you want. Sometimes, though, their star just hits the ball over the wall.

Ben is a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @benclemens.

Perhaps the Giants could sign an Olympic high jumper to play left field, or one of the Flying Wallendas. Let’s see Machado hit the ball over THAT!