2023 Contemporary Baseball Era Committee Candidate: Don Mattingly

The following article is part of my ongoing look at the candidates on the 2023 Contemporary Baseball Era Committee ballot. Originally written for the 2013 election at SI.com, it has been expanded and updated. For a detailed introduction to this year’s ballot, use the tool above. An introduction to JAWS can be found here.

Don Mattingly was the golden child of the Great Yankees Dark Age. He debuted in September 1982, the year after the team finished a stretch of four World Series appearances in six seasons, and retired in 1995 after finally reaching the postseason — a year too early for the franchise’s run of six pennants and four titles in eight years under Joe Torre.

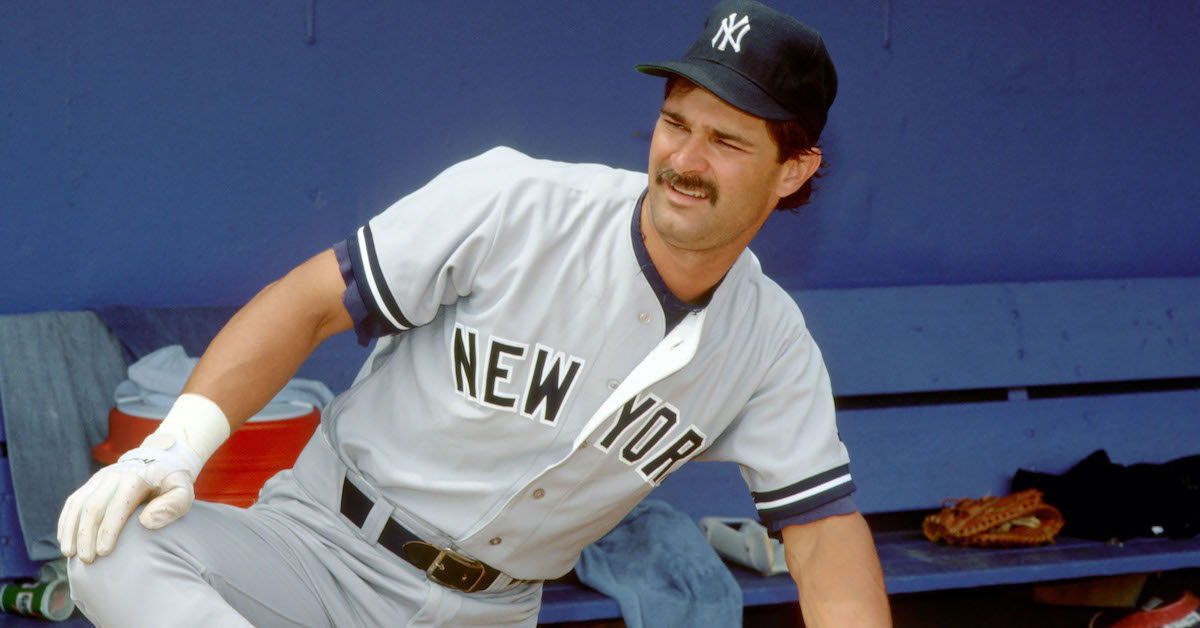

A lefty-swinging first baseman with a sweet stroke, “Donnie Baseball” was both an outstanding hitter and a slick fielder at his peak. He made six straight All-Star teams from 1984 to ’89 and won a batting title, an MVP award, and nine Gold Gloves. Along the way, he battled with owner George Steinbrenner even while becoming the standard bearer of the pinstripes, the team captain, and something of a cultural icon. Alas, a back injury sapped his power, not only shortening his peak but also bringing his career to a premature end at age 34. At its root, the problem was that Mattingly was so driven to succeed that he overworked himself in the batting cage.

“Donnie was one of the hardest workers I had ever seen and played with. He would go in the cage before batting practice and take batting practice. And after batting practice was over, he’d take batting practice,” former teammate Ron Guidry said for a 2022 MLB Network documentary, Donnie Baseball (for which this scribe was also interviewed).

“I should have learned quicker to not to beat my body up, and if I did less, I could perform better,” said Mattingly for the same documentary.

Mattingly debuted on the 2001 Hall of Fame ballot, the last one before I began my own annual reviews, but it was quickly clear that he didn’t have the raw numbers or the support of enough voters to gain entry to Cooperstown. After receiving 28.2% his first time around, he dipped to 20.3% in 2002, spent most of the remainder of his 15-year run in the teens, and was in single digits by the end. What’s more, in two appearances on the Modern Baseball Era Committee ballot in 2018 and ’20, he failed to reach the threshold to have his actual share reported; at most, he received three of 16 votes (18.8%) in his last appearance.

At this point, Mattingly’s best hope for a Hall of Fame berth involves building on his managerial success, though even in that department he has a long way to go. After winning three division titles in five seasons with the Dodgers, he spent seven years toiling for the Marlins and is currently out of a job after stepping down from that job last month. He seems unlikely to be elected this time around, but his candidacy is nonetheless a welcome palate cleanser when compared to the likes of Rafael Palmeiro and Albert Belle.

| Player | Career WAR | Peak WAR | JAWS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Don Mattingly | 42.4 | 35.8 | 39.1 |

| Avg. HOF 1B | 65.5 | 42.1 | 53.8 |

| H | HR | AVG/OBP/SLG | OPS+ |

| 2,153 | 222 | .307/.358/.471 | 127 |

Mattingly was born on April 20, 1961 in Evansville, Indiana, the youngest of five children of Bill (a mailman) and Mary Mattingly. He honed his baseball skills at a young age, playing Whiffle ball in the backyard with his brothers and other kids three or four years older. It was in that yard that he learned to hit to the opposite field, because anyone who hit the tree hanging over the field on the first base side was out, while hitting the family garage in left field was a home run. “I think about it now being a dad, how many times that Whiffle ball hit that metal of the house. I wonder what my mom and dad were thinking,” he said in a 2002 Yankeeography video for the YES Network.

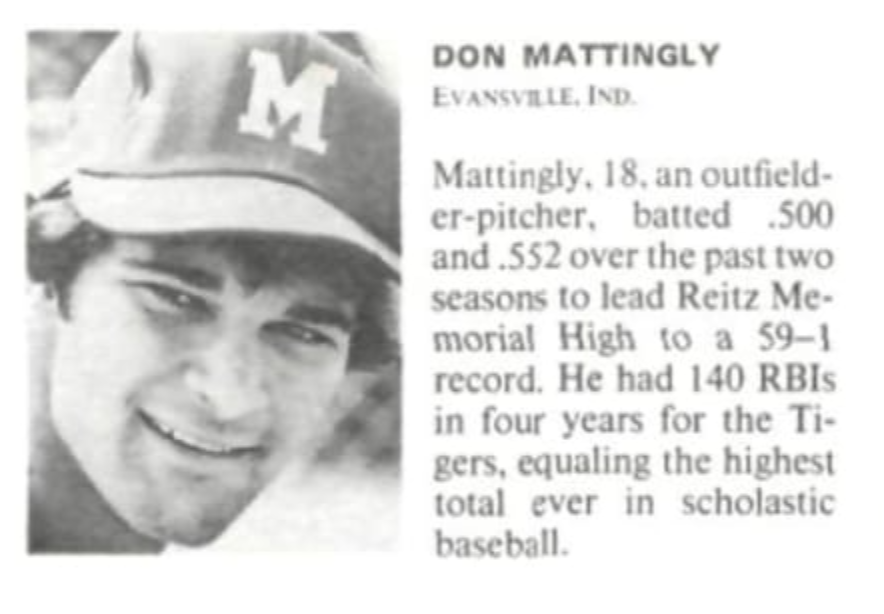

In addition to his ability to go oppo, Mattingly was ambidextrous. In Little League, he switch-pitched occasionally, throwing three innings righty and three more lefty. At Reitz Memorial High School, he was a three-sport star, starting at quarterback and point guard as well as an outfielder/pitcher. He helped Reitz Memorial to a 59-game winning streak that included a state championship in his junior year, earning him a spot in Sports Illustrated’s July 16, 1979 “Faces in the Crowd” feature

By the time of the 1979 draft, Mattingly had committed to attend Indiana State University on a scholarship, but the Yankees chose him in the 19th round, and he surprised his family by deciding to sign for a $23,000 bonus. He began his professional career at Low-A Oneonta, where he hit .349/.444/.488; the next year, he batted .358/.422/.498 with nine homers and 105 RBI at A-level Greensboro. While his lack of speed and power concerned the Yankees to the point that they considered moving him to second base because of his ability to throw right-handed, he topped .300 at every stop in the minors with good plate discipline and outstanding contact skills, even if he never exceeded 10 homers.

Mattingly was called up for a cup of coffee in September 1982, making his debut on September 8 as a defensive replacement for left fielder Dave Winfield. He made one start and six appearances off the bench, mainly in left, and went 2-for-12, though it took him until October 1 to collect a single off the Red Sox’s Steve Crawford for his first hit. While he broke camp with the Yankees the following spring, he played in just four games before being sent back to Triple-A Columbus while Ken Griffey covered first base. Recalled in late June after Bobby Murcer retired, he split his time between the outfield (48 games, including one in center) and first base (42 games), batting a thin .283/.333/.409 (107 OPS+). He even made one appearance as a lefty-throwing second baseman during the August 18 completion of the infamous George Brett “Pine Tar Game.”

While manager Yogi Berra initially planned to use Mattingly to back up first base and both outfield corners in 1984, he won the starting first base job in spring training and emerged as a bona fide star, thanks in part to the help of hitting coach Lou Piniella, who taught him to keep his weight back and to apply backspin to the ball. From a 2021 interview with colleague David Laurila:

“More than anything, Lou Piniella had a huge impact on me going from a guy that was hitting doubles to a guy that was hitting doubles and homers. It was really nothing more than basically learning how to backspin the ball. I’d been more of a top-hand guy that hit a lot of topspin balls in the gap; I thought I hit them really well, they just didn’t go out. I’d always be kind of surprised, because I felt like I crushed it. Then I learned to use the bottom hand, and shorten my route, which unleashed more power.”

Mattingly hit .343/.381/.537 with 23 homers and 110 RBIs, leading the league in batting average, hits (207), and doubles (44), ranking fifth in WAR (6.3), and beginning his All-Star run. He matched that year’s 156 OPS+ in 1985, accompanying it with 35 homers, a league-high 145 RBIs, and 6.5 WAR en route to the AL MVP award. The Yankees won 97 games that year, their most ever during his 14-year career, but they finished two games behind the Blue Jays in the AL East standings.

Mattingly was even better offensively in 1986, leading in hits (238), doubles (53), slugging percentage (.573) and OPS+ (161) and placing second in batting average (.352, just behind Wade Boggs‘ .357), third in WAR (7.2, behind Boggs and Jesse Barfield), and fifth in on-base percentage. His numbers took a dip the following year when he missed nearly three weeks due to a back injury that was rumored to have been sustained while wrestling teammate Bob Shirley in the clubhouse; Mattingly denied that was the cause, saying that he believed he suffered the injury fielding grounders during batting practice. Though he was diagnosed with two protruding discs, he actually hit better after returning (.336/.371/.601 with 24 homers) than before (.311/.390/.485 with six homers). That post-injury stretch included his tying a major league record by hitting home runs in eight consecutive games on July 8–18, interrupted by the All-Star break.

Though Mattingly was not quite as productive from 1987 to ’89 (.313/.360/.498 for a 136 OPS+ and an average of 4.3 WAR) as he’d been in the three years prior (.340/.382/.560, 158 OPS+, and an average of 6.7 WAR), he remained an All-Star caliber player. But that still wasn’t enough to help the Yankees get over the hump. They won an average of 91 games from 1983 to ’87 with the aforementioned peak of 97 but always finished at least two games out of first place in AL East, and generally more than that. As the team slipped to 85–76 in 1988, Mattingly caught flak from Steinbrenner over his relatively high salary — he’d signed a three-year, $6.7 million contract the previous offseason — and inability to produce a championship singlehandedly. The Boss called him “the most unproductive .300 hitter in baseball,” a ridiculous notion given that over his first four full seasons, Mattingly’s .560 slugging percentage and 483 RBI — the industry’s shorthand for productivity during that era — had both led the entire majors.

Mattingly didn’t take the criticism lying down, telling reporters, “There’s no respect. They give you money and that’s it. That’s as far as it goes. They think money is respect. Call us babies, call us whatever you want. If you don’t treat me with respect, I don’t want to work for you.” He added, “It’s hard to come to the ballpark when you’re not having any fun… This is the first season I’ve had to fight myself to play the game every day.”

Mattingly continued his All-Star-caliber play through 1989, but back troubles limited him to a total of 41 home runs in ’88–89. For the 1984–89 period, the six full seasons of his prime, he hit a combined .327/.372/.530 for a 147 OPS+, averaging 27 homers and 5.5 WAR; in that timespan, only Boggs, Rickey Henderson, Cal Ripken Jr., Ozzie Smith, Alan Trammell, and Tim Raines were more valuable.

Unfortunately, Mattingly’s career began going downhill just as he signed a five-year, $19.3 million extension in April 1990. He hit just 14 homers and slugged .370 in 1990–91, missing seven weeks of the former season due to further back troubles. In the spring of 1991, he was named team captain, filling what had been a void for two seasons following Guidry’s retirement. Even so, he was famously benched for one game in August and fined $250 because his hair was long enough to touch his collar, violating a team rule. At that point, he told reporters that he had quietly asked general manager Gene Michael, who at this point was running the organization in the absence of the suspended Steinbrenner, for a trade in June, but was rebuffed. Upon being benched, a defiant Mattingly said, “Maybe I don’t belong in the organization anymore,” called Michaael’s enforcement of the hair policy “petty,” and added, “He wants an organization that will be puppets for him and do what he wants.”

Contrary to popular assumption, the hair incident didn’t occur until after a similar situation was lampooned on The Simpsons‘ baseball-themed “Homer At the Bat” episode in which Mattingly guest-starred:

In Donnie Baseball, Mattingly admitted that he’d never seen the full episode and had only viewed the clip once or twice — a scandal right up there with Fred McGriff’s admission that he’d never seen the Tom Emanski’s Baseball Defensive Drills video commercial that gained him such notoriety.

Mattingly escaped his two-year funk but was never again a true offensive force, hitting .292/.345/.422 for a 110 OPS+ with an average of 11 homers and 1.9 WAR from 1992 to ’95. He did, however, stick around long enough to experience the beginning of the Yankees’ competitive revival, first via an AL-best 70–43 record in the strike-shortened 1994 season and then a Wild Card berth via a 79–65 record in ’95. In a bittersweet coda, he hit .417/.440/.708 in a losing cause during the 1995 Division Series against Piniella’s Mariners, his lone taste of postseason play but his final days as a player.

After eight years away from the game, Mattingly returned as a coach for the Yankees in 2004 under Torre. When Torre and the Yankees parted ways after the 2007 season, he was a finalist to take the reins, but general manager Brian Cashman instead chose Joe Girardi, with the backing of Steinbrenner and his sons, Hank and Hal. The spurned Mattingly followed Torre to the Dodgers, spending one season as hitting coach and two as bench coach before taking over as manager himself. Though he guided the Dodgers to a .551 winning percentage in five years and won three straight NL West titles from 2013 to ’15, he parted ways with the team after his 92-win ’15 season. That allowed president of baseball operations Andrew Friedman, who had taken over the previous year, to get a fresh start with a new manager, Dave Roberts.

Mattingly in turn became manager of the Marlins and spent seven years at the helm before deciding to leave; perpetually stuck in rebuilding mode, Miami won at just a .430 clip on his watch, and lost 93 or more games four times. Mattingly did pilot the team into the postseason for just the third time in franchise history in 2020, when the Marlins went 31–29 and then swept the Cubs in the Wild Card Series before bowing to the Braves in the Division Series. For four of those seasons (2017–21), he worked under CEO Derek Jeter, with whom he had briefly played in 1995 and later coached. For his career, Mattingly is 889–950 (.483) as a manager.

…

Because he retired at age 34, Mattingly wound up with rather light career totals, both traditional and advanced, giving himself quite an uphill battle for Cooperstown. In the post-1960 expansion era, only one position player has retired at 34 and reached the Hall of Fame: Ron Santo, whose election came 37 years after his retirement, via the 2012 Veterans Committee ballot (and, alas, posthumously). Of the position players whose final year was at age 35, Johnny Bench and Kirby Puckett were first-ballot Hall of Famers thanks in large part to their connections to multiple championship teams, but Richie Ashburn and Bill Mazeroski had to wait decades for election via the VC. A contemporary of Mattingly’s, Ryne Sandberg, retired at 34 but, after sitting out one season, returned to play two more and was then elected by the writers in 2005.

In terms of advanced statistics, Mattingly’s 42.4 career WAR is about 23 wins below the standard and ranks 45th in career WAR among first basemen, below all but two of the 23 enshrined non-Negro Leagues first basemen: Jim Bottomley and High Pockets Kelly. His 35.8 peak WAR is 6.3 wins below the standard and ranks 33rd at the position, below 16 of the 23 Hall of Famers, and his 39.1 JAWS ranks 39th, two spots above the recently elected Gil Hodges but ahead of only two of the other 23. He’s seven spots below McGriff (44.3 JAWS) and even further behind Mark McGwire, Keith Hernandez, John Olerud, and Will Clark, all of whom were bypassed for this ballot.

Mattingly received 28.2% of the BBWAA vote in his debut, but within two years, his support dwindled to less than half that; over his final 13 years on the ballot, he cracked 15% just twice, and fell below 10% three times. He was one of three candidates grandfathered into the Hall’s 2014 decision to truncate candidacies from 15 years to 10; he was heading into his 15th and final year of eligibility at the time and received just 9.1% of the vote, a gain of 0.9 points from the year before. Trammell, who was in his 14th year at that point, received 25.1% but surged to 40.9% the next year, and was elected by the Modern Baseball Era Committee two years later. Lee Smith, who was in his 13th year, inched upwards from 30.2% that year to 34.2% in his final year, and was elected on the 2019 Today’s Game ballot.

It seems highly unlikely that Mattingly will follow that pair into Cooperstown, and it’s difficult to see any justification to vote for him on this ballot. As I noted three years ago, if he’s going to get elected, it will have to be as his mentor Torre did, as a manager — only now, the 61-year-old Mattingly is going to have to find a job first.

Brooklyn-based Jay Jaffe is a senior writer for FanGraphs, the author of The Cooperstown Casebook (Thomas Dunne Books, 2017) and the creator of the JAWS (Jaffe WAR Score) metric for Hall of Fame analysis. He founded the Futility Infielder website (2001), was a columnist for Baseball Prospectus (2005-2012) and a contributing writer for Sports Illustrated (2012-2018). He has been a recurring guest on MLB Network and a member of the BBWAA since 2011, and a Hall of Fame voter since 2021. Follow him on BlueSky @jayjaffe.bsky.social.

Not really close to a HOFer. Just so many guys at this level. Whenever I think of potential HoF 1Bman, I think of the 3 Jays 1Bman in the 90s and 2000s: McGriff, Olerud, and Delgado. None are in the HoF and all are fairly close. Did Mattingly have a better career than those guys? Pretty clearly worse than Olerud and McGriff and not any better than Delgado.