A Brief Note on the Sulks, the Blues, and Other Such Ailments

Everyone gets the blues. Sometimes it’s for obvious, “good” reasons, like a global pandemic upending your life and taking hundreds of thousands of others. Sometimes it’s for complicated reasons, like bad brain chemistry and the reverberating effects of trauma. And sometimes it’s for trivial reasons, barely any reason at all. You lose at a game. You trip on a rock. You make a small, forgivable error at work. A tiny thing, in combination with the many other tiny things that make up life, can cast a pall over the ensuing several hours — even days.

Baseball players, being human people, are also subject to the occasional onset of the blues. The public nature of their jobs, though, can make the stakes of these incidences much higher: A small, forgivable error on the field, timed poorly, is a national disgrace, or a step toward the public, humiliating loss of one’s job. And with higher stakes come more dramatic reactions from the players. Reactions like, say, suddenly disappearing.

***

“Rabbit” Sturgeon — that’s how he was always referred to in a baseball context, never by any real, non-animal name — seems to have been born somewhere in Minnesota. He reported his age on the 1930 U.S. Census as 45, putting his birth date around 1885. There’s nothing much on the public record about his early life, but when William E. Sturgeon was around 20, he got into the two professions that would come to define the rest of his life: the railway and baseball.

Rail in the U.S. was hitting its peak at the beginning of the 20th century, and increased regulation made the historically dangerous jobs involved in railroad operations rather less so. Still, doing such work was hardly easy, and the job of a brakeman was one of the most notoriously difficult. Brakemen were responsible for the application of brakes — a simple-sounding but absolutely vital task, especially when massive freight trains were involved. Brakemen also made sure that the axle bearings of train wheels weren’t overheating, kept an eye out for stowaways, and ensured that cargo and passengers were safe.

William Sturgeon was already a brakeman by the time he broke into Northwestern League baseball in the spring of 1907. A shortstop, he’d already been playing on smaller-time teams for several years, earning himself the nickname “Rabbit” for his speed and cleverness — skills that were surely jointly applicable to his job on the rails. In March, he earned a place on the spring training roster of the Butte Miners in Idaho. The newspapers referred to him as “the brakeman shortstop,” and as the season approached and the team coalesced, there was a good deal of excitement about the Rabbit’s performance. On the last day of March, Rabbit had his best game yet with the Miners: he went 4-for-4, with one of those four hits being a game-winning two-RBI triple.

On Saturday, April 6, a few things happened with the Miners. Manager Russ Hall named second baseman Ed Bruyette captain of the team — an honor that Bruyette apparently didn’t want, but was forced to accept regardless. Hall also signed lefty pitcher Clyde Parks of Walla Walla — the first signed contract of the season. And, that Saturday, Hall and the rest of the team began to worry that Rabbit Sturgeon had gone missing.

Several days prior, during a scrimmage, Hall had decided to shake things up a little bit, playing Rabbit in the outfield and someone else in his customary spot at short. Rabbit — to put it lightly — didn’t take it well. As the Spokane Spokesman-Review reported: “While in the field ‘Rabbit’ contracted a case of the sulks, getting so dumpy that he even refused to pick up a ball and return it to the pitcher.” He had not been seen since that game, and no one had any news of his whereabouts.

By the time the Butte Daily Post picked up the story on April 10, Rabbit was still missing. In Lewiston, Idaho, the sports page pondered the roster implications of Rabbit’s flight, noting that his disappearance left Hall with only three players to cut. And then — nothing. The assumption was simply that Rabbit had quit the team, and his disappearance ceased to be a matter of public concern.

Where did Rabbit go during the weeks of silence? Did he return to the rails, or perhaps return home? And why did that one incident shake his desire to play baseball so much that he decided to flee the sport entirely — even though, in his other line of work, he would have dealt regularly with far more stressful situations? There are so many different circumstances that could have driven that case of the sulks. The reality is that no one, except for maybe Rabbit and his family, really cared.

***

A month later, on May 18, Rabbit resurfaced in Spokane and was signed to the team there. He eventually ended up back in Butte, with Russ Hall — clearly, he had been forgiven. There were no more disappearances in his baseball career after that. He played for at least a decade more, traversing eight different professional leagues and, ironically, moving to the outfield, before settling in Livingston, Montana. Even after his career ended and he moved to the railway full-time, he was still Rabbit. Tales were told of his exploits in the Livingston papers decades later: Rabbit, the story goes, played against Walter Johnson in his final game before moving to the big leagues, and had, by virtue of the wit and speed that made him who he was, scored the lone, game-winning run against the Big Train.

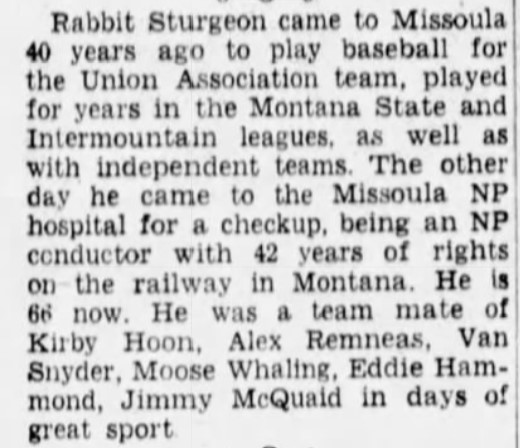

The last mention of Rabbit I could find was this note in the Missoula Missoulan, almost 50 years after Rabbit’s disappearance:

In all the stories told of Rabbit’s career, there is nothing mentioned of that case of the sulks, nor his disappearance. No matter what he thought he would do, standing there in the outfield, believing that his position was being given to someone else — no matter how long he was gone for. He came back, and he played again. He played well. That is what mattered, in the end.

RJ is the dilettante-in-residence at FanGraphs. Previous work can be found at Baseball Prospectus, VICE Sports, and The Hardball Times.

Walter Johnson was not playing for a minor league team in 1907, but a company team which may well have played exhibition games against minor league teams. I don’t know if box scores exist in newspapers of that area and time, but it may be possible to do tracer on that story. The Butte team that Rabbit Sturgeon played on that year was in the class B Northwestern League, all of the rest of his pro career was in class C or D leagues.

At this time the minors had already taken a few steps along the road to complete subjugation to the majors. The system we have today, with all of the organized minors being farm teams for the majors, is bad for baseball in very many ways.

I’ve greatly enjoyed these articles. Keep up the good work.