A Surgical Probe into the State of Chris Sale and the Boston Red Sox

Getting a major, non-emergency surgery is a strange experience. One moment you are yourself, living in the body you have always inhabited, even if that body is now dressed in an unfamiliar and unflattering set of garments foisted upon you by the nurses. You are then wheeled into a cavernous room, where you are laid out on a slab for dissemination, surrounded by a motley crew of strangers with covered faces. Some bustle around with arcane metal implements; others pat you on the shoulder and tell you to have good dreams, thereby placing an unnecessary amount of pressure on you not to have bad dreams, in which case you would have failed at one of your two tasks in this scenario. (The other task is, of course, not dying.) And in what seems like moments (but also seems like a very long time, somehow), you wake up confused, unable to move or speak, with your body permanently altered in ways that you will likely never be able to fully understand. In just a few hours of unawareness, your experience of reality is fundamentally changed. There is nothing you can do but try to adjust.

The last baseball game I watched before I went under was the Mariners home opener. The Mariners played this game against the defending World Series champion Boston Red Sox and ace Chris Sale, and they won 12-4. Save for their poor defense, they looked all-powerful. The Red Sox looked uniformly awful. The baseball season is full of these little flauntings of expectation: fun, ultimately insignificant. A larger data set irons everything out in the final reckoning. When I got knocked out for surgery in the early morning on March 29th, I had differently-arranged bones, no titanium screws or plates in my body, and a fundamental, unshakeable understanding that the 2019 Seattle Mariners were not, and the 2019 Boston Red Sox were, a reliably excellent baseball team.

I spent the several days post-surgery in a quasi-real state, drifting in and out of consciousness, oozing blood from various orifices, unable to eat much more than hospital-issue jello. When I got home, I tried to watch some baseball. My attention drifted with such hazy determination that it seemed as though a higher power were directing it away, and even without that, I couldn’t stay awake for three hours on end. As my energy and ability to function gradually returned, I was confronted by the massive backlog of undone tasks and unresponded-to emails that appears when you disconnect from the world for a few days.

And so it happened that I didn’t really get a chance to clue back into the baseball universe until this weekend. The world that greeted me was nothing short of astonishing. While I was gone, the Mariners had become the greatest offensive juggernaut that has ever been seen in the history of professional baseball. The Red Sox, meanwhile, had continued to be awful. Just awful! It was astonishing, an astonishing truth to reckon with, especially while on four different kinds of medication.

One reliable element of this new reality, though, was that the Blue Jays were terrible. The team has a collective wRC+ of 63, which in layman’s terms could be described as “ass.” I have seen the Red Sox beat the Blue Jays many, many, many times, and I have seen Chris Sale dominate the Blue Jays many, many times since he made the move to the Red Sox. In 43 innings pitched against the Jays with the Red Sox prior to this season, he allowed but 11 earned runs, and struck out 37.9% of the batters he faced, which has made for some frustrating baseball-watching experiences as a Jays fan. But as an appreciator of all things Sale — the violence of his pitching motion, the sweep of his slider, his cryptid-like frame and terrifying demeanor, his alleged belly-button piercing — watching him pitch against the Jays is a treat.

And there he was on Fenway’s Opening Day, a day of celebration, a reminder of the indomitable World Series championship team of last season, and a reminder that the team taking the field this season is much the same one. The fans were loud, and the weather was gloomy. This was the first game since my surgery that I had a chance to sit down and really focus on; and this, at last, was comfortingly familiar. The Red Sox were an anchor in my sea of uncertainty, the team connecting my pre-op baseball experience to my post-op existence.

For the first three innings, the game wasn’t much more than a great opportunity to catch up further on my rest. Sale retired the first seven batters he faced. His fastball velocity, a matter of justifiable concern for him this season, was up from his last start (though he still failed to generate any swinging strikes with the pitch). Same old 2019 Blue Jays. Same old Chris Sale. The Red Sox managed to score a pair of runs off Matt Shoemaker; everything was as it should be. Sale struck out Richard Urena to lead off the top of the third.

Then Alen Hanson poked a high slider into left field.

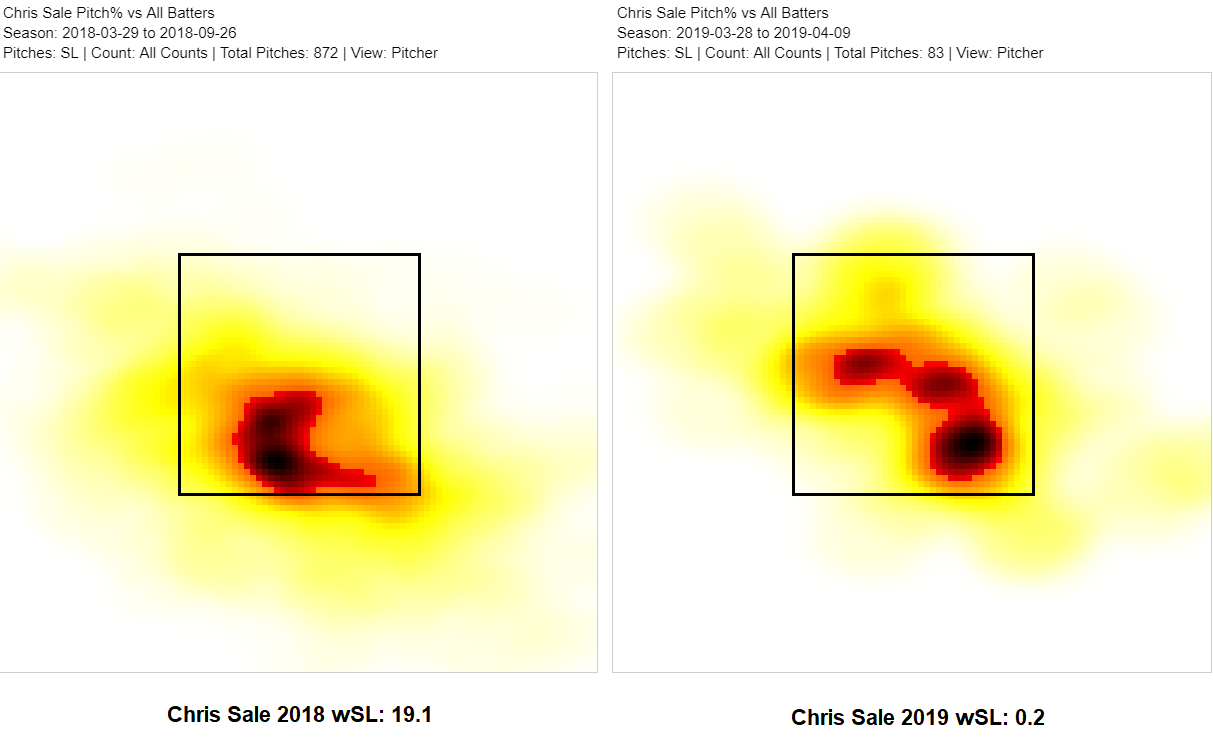

It was not a good pitch — Sale’s slider, like virtually all his other pitches, has not had its characteristic venom so far this season. He has not located the pitch well, and this one, too, was poorly placed, high and hanging over over the center of the plate. The ball was not exactly well-hit either, though, and it was just the one baserunner. No big deal. Nothing to see here.

Then Billy McKinney poked another high slider into center field. This slider was a better one — harder, coming at 81 mph instead of 77, and floating less casually over the plate — and McKinney hit it softly, without much conviction. But now, all of a sudden, the Jays had a rally brewing. (The Jays have had three or fewer hits in four of their 12 games this season.) And on Sale’s first pitch to Freddy Galvis, with the hit and run on, the Jays turned that rally into a scoring play. A sac fly tied the game on the next batter before the inning came to a close.

This sequence of events was bizarre to witness — the hit and run actually working, and the Jays managing to get enough runners on base to make the hit and run a viable possibility. As it turned out, the real break in the fabric of reality was yet to come.

The top of the fourth began with yet another single, this time by Randal Grichuk, off a slider that failed to sweep across the plate, instead hanging up and out of the zone on Sale’s armside. (Last year, 48% of swings generated by Sale’s slider were whiffs; this year, that number has dropped to only 28%. Sale threw 26 sliders against the Blue Jays; he generated five swinging strikes against seven balls in play.) This was promptly followed by a Danny Jansen single on a fastball out of the zone, which was promptly followed by an aborted bunt attempt by Lourdes Gurriel Jr. Perhaps confused by the sudden switch from bunting to not-bunting, Christian Vazquez let the ball bounce off his glove.

Grichuk advanced to third. And after a long plate appearance, which included at least one other failed bunt attempt, Gurriel finally shot a single into right field. The Jays had their second three-hit inning of the day, and they had the lead again.

By this point, I felt like I was losing my mind. While all of these singles were certainly the result of some amount of contact-related BA(d)BIP luck, and the passed ball was certainly not his fault, the fact that Sale was allowing this much contact at all — that, almost two weeks after that fateful game the day before my surgery, he looked almost as bad as he had back then — that the Reliably Excellent Red Sox had the same number of wins as my sad little Blue Jays, and that those same Jays now had the lead — none of it made sense. None of it tracked with the concept of baseball reality I had nurtured through my absence. I wondered if the painkillers were eating away at my brain cells.

A sacrifice bunt moved the two baserunners over. Hanson struck out swinging for the second out of the inning. The put-away pitch was Sale’s first swinging strike generated on a four-seamer this season, yet another fact that makes me feel that I have phased into a different dimension of existence. Sale stood for a moment, his jersey rippling gently in the wind, signifying a peace and tranquility that would never come. He threw to the plate, and Vazquez assumed an ideal catching position.

The ball sprang away. One runner came home; the other, Gurriel, scampered to third — from whence he proceeded to do this.

A straight steal of home, on a ball thrown a mile wide of the plate, after an inning where a catcher was possessed by the departed spirit of Rudy Kemmler, and a team with a .193/.268/.320 collective line put together two three-hit rallies. How does one even react appropriately to this? What’s the precedent?

The inning ended with no further runs, and Sale left the game, but its effects lingered, rippling through the chilly air, through the frequency of the boos that rained down onto the field from the Red Sox faithful. Something was off. This was not what was supposed to be happening. The team faded out for the winter, and when they woke up in the spring — the same team with the same players who had won the World Series — their experience of reality had fundamentally changed. The Red Sox fell to 3-9, in the cellar of the AL East. Their playoff odds, sitting at 88.7% on Opening Day, have nosedived to 63.4%.

Yet that’s still a better chance than not. It’s still better than the Rays, who have flapped their slimy ray wings and glided into first place. Sale says that he’s never felt this lost, but the likelihood of him remaining lost forever seems slim. The experience of reality has changed, but most of the time, things have a way of smoothing over, of returning to the way that they’re supposed to be. Most of the time, the statistics normalize; the issues are problem-solved; the physical and mental injuries are recovered from. The pitcher who’s losing his fastball finds different ways to pitch. The cracks where the bones were separated fuse together again. Something has changed — it will heal, eventually. The titanium screws will always be there, but you’ll largely forget they exist. You just have to survive the adjustment period.

RJ is the dilettante-in-residence at FanGraphs. Previous work can be found at Baseball Prospectus, VICE Sports, and The Hardball Times.

Thank you Rachael, very cool!

Can someone please punt Cave Dameron into the sun.

No u