AJ Smith-Shawver and the Dead Zone Slider

The Braves are the best team in baseball right now. They were the first team to clinch their division, and their title odds are nearly double that of any other squad. Their leadoff man, Ronald Acuña Jr., is gunning for a 40-70 season, and their cleanup hitter, Matt Olson, just hit his 52nd homer of the year, surpassing the franchise’s single-season record. Oh, and they have six other All-Stars besides that pair, including one of the favorites to win the FIP Cy Young in Spencer Strider.

If the Braves have shown any weakness this season, it’s been their relative lack of starting pitching depth. They’ve had a trio of 29-game starters in Strider, Bryce Elder, and Charlie Morton, and while all of them have showcased their warts down the stretch, the main problems for the rotation were the absences of last year’s ace — Max Fried — and breakout starter — Kyle Wright. Though he’s made just 13 starts on the season (the fourth most on the team), Fried is back now, and he’s looking pretty darn good, rounding out what should be an excellent four-man playoff rotation, so the Braves’ issues with depth (and Wright’s struggles) likely won’t matter as much in October. Yet, they left me scratching my head at times this season when they passed over top prospect AJ Smith-Shawver for starts in Fried and Wright’s absence.

Smith-Shawver is 20 years old and hadn’t topped 70 innings in pro ball before this season. But he’s also been on a fast track through the minors and carries much more upside than any of the Braves’ other depth options — especially the likes of Yonny Chirinos, who miraculously made just as many major league appearances with Atlanta as Smith-Shawver this year. Yes, there are service time and innings considerations for Smith-Shawver, and the right-hander dealt with a bout of shoulder inflammation that sidelined him for a couple weeks, but his most recent stint in the majors made me wonder whether there’s something more to the Braves’ hesitancy to use him. Specifically, Atlanta recalled Smith-Shawver last Sunday in advance of their doubleheader Monday, but he didn’t appear in a single game, languishing on the major league roster until Wednesday when he was demoted again.

Immediately upon digging deeper, Smith-Shawver’s slider jumps out to me. As of the end of the day Saturday, his slide piece averaged an exceptionally low 1,916 rpm, the third lowest among the 507 hurlers who’ve tossed at least 50 sliders and/or sweepers this season. Spin rate, along with spin axis and active spin, determines pitch movement. Yet, some sliders — like Ian Hamilton‘s 1,514 rpm slambio and Dauri Moreta’s 1,984 rpm… thing, to name a pair that have already been investigated — succeed at least in part due to their low spin rates and resulting lack of break.

In Moreta’s case, his primary offering induces just .04 inches of rise, the fifth closest to zero among the 2,220 pitches thrown at least 50 times this year; the pitch has saved the Pirates hurler four runs per Statcast’s run values. Hamilton’s slambio, on the other hand, induces 3.4 inches of rise but also just 1.1 inches of horizontal movement; since it alternates between cutting gloveside and running armside, diluting the horizontal average, it actually averages about five inches of total movement, but that still ranks 47th lowest among the aforementioned group. The pitch has saved the Yankees reliever 11 runs.

The bottom line is that the way these pitches succeed is by surprising the hitter; the slambio has cutter/slider spin, but not much of it, so it doesn’t move as much as hitters might expect given its spin direction. Moreta grips his whatever-it-is like a slider, and horizontally, it moves in the opposite direction from what you’d expect, which certainly fools hitters, but it wouldn’t be complete without its ability to kill vertical movement as well. Regardless of which category they belong in, this lack of vertical movement has led to the two pitches inducing fly ball rates that would be below average for every pitch type except forkballs, sinkers, and splitters.

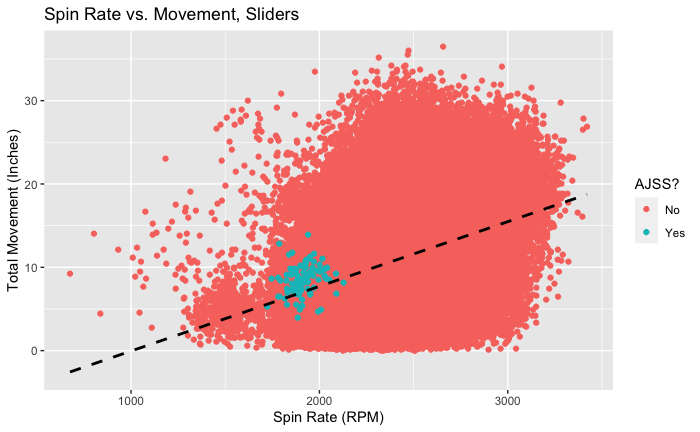

So the low spin rate on Smith-Shawver’s slider probably kills its movement in order to help it succeed too, right? Well, its movement is below average, but still higher than you’d expect based on spin rate alone:

That’s probably because Smith-Shawver is running a 17% spin efficiency on his slider, per Alan Nathan’s calculations. Spin efficiency is the same as active spin; that is to say, it’s the percentage of a pitch’s spin that contributes to movement. No wonder the relationship between raw spin rate and total movement isn’t that strong above; sliders as a whole only average a 25.1% spin efficiency.

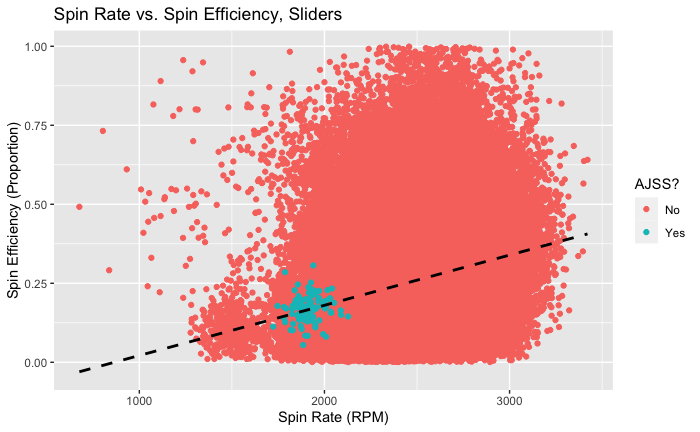

Yet even though Smith-Shawver has a below-average spin efficiency on his slider, it’s right around what you’d expect given his spin rate:

Full disclosure, this result surprised me. My thinking was as follows: At one end of the slider spectrum is the gyro, a very low spin efficiency pitch that you might know as a “bullet” slider, which relies largely on gravity for its drop and bat-missing ability. Spinning like a football around an axis parallel to its velocity vector, the spin on the pitch won’t alter its movement, leaving its fate to Newton’s whims. On the other end, there’s the sweeper or “rising” slider, which relies on side-to-side movement — courtesy of sidespin — instead. Sweepers tend to have higher spin efficiency (44.2% average) due to their reliance on this spin-induced movement.

Non-sweeper sliders have averaged a 20.4% spin efficiency this year. However, this includes some sliders that really fall in between sweepers and true gyros. Using Nathan’s calculations, a gyro has more like a 10% or less spin efficiency. Given that gyro sliders are characterized by their lack of active spin, it stands to reason that the pitchers who throw them might look to kill the overall spin rate on the pitch, too; even a 10% spin efficiency means two different things for a 1,900 rpm wobbler and a 2,700 rpm spinner.

In other words, I thought that there would be a stronger relationship between spin rate and spin efficiency for sliders, and I thought that Smith-Shawver would be an outlier, throwing his wobbler with too high a spin efficiency. So the question becomes: Why isn’t there a stronger relationship?

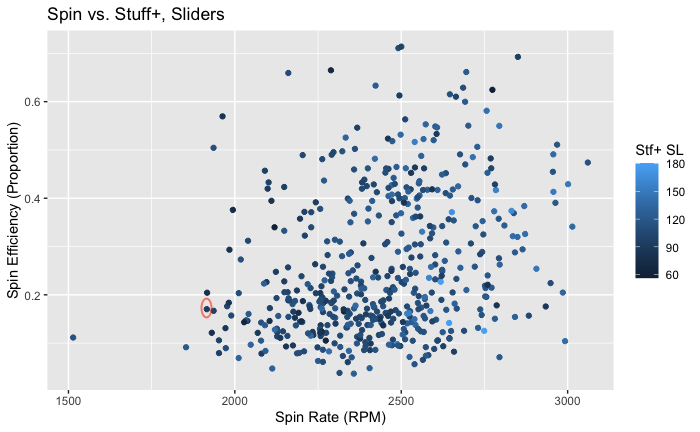

One answer could be that spin efficiency and spin rate are hard to control, and even harder to align. But that left me unsatisfied. Even if spin is hard to control, that doesn’t mean there isn’t a connection between spin rate, spin efficiency, and slider effectiveness. In that case, it might mean that teams just haven’t selected for pitchers with the right combination of all three variables yet. Run value is a bit noisy, so I instead opted to use Stuff+ values to measure (expected) effectiveness. Stuff+ doesn’t distinguish between sweepers and sliders, so I tried lumping them together first. Here’s how that turned out, with each dot representing all of a single pitcher’s sliders and/or sweepers (with Smith-Shawver circled in red):

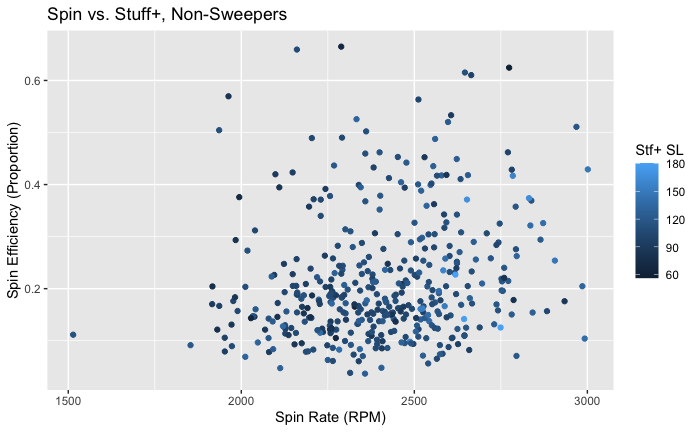

Clearly, more spin is typically better in the eyes of Stuff+, regardless of spin efficiency; there’s a lot more light blue to the right side of the graph. This seemed to be the case even when I excluded pitchers whose sliders included 50% or more sweepers:

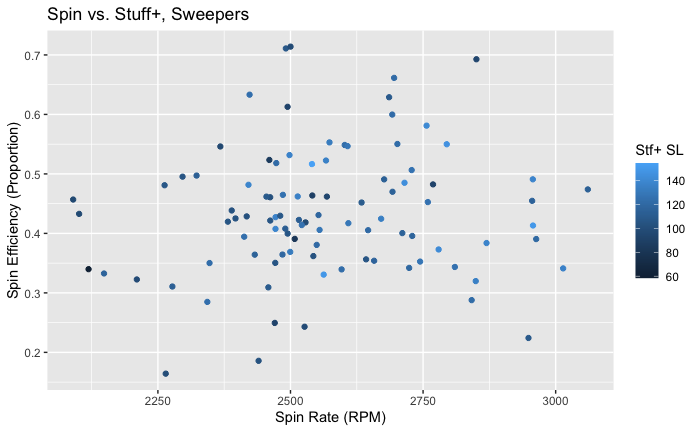

Or when I only looked at those sweeper-heavy pitchers:

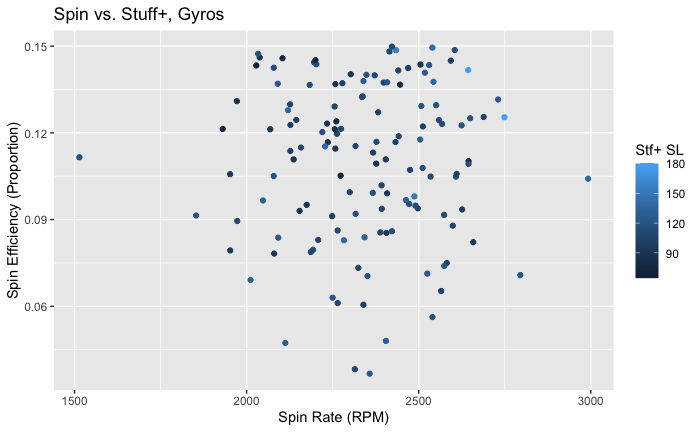

At the very bottom of the spin efficiency barrel, there doesn’t seem to be as much of a relationship between spin rate and Stuff+, but it’s still there:

The relationship seems to dissipate even more if you focus on pitches with spin efficiencies below 10%, which I demarcated as true gyros, but there simply aren’t enough of them (48) to make a conclusive judgement. So, I also included some borderline gyros (15% spin efficiency or lower), which seemed to follow the trend more closely, though still not as much as the sweepers.

A gyro may be the better option for a pitcher with low spin rates looking to add a slider, but that doesn’t mean low spin rates are good for a gyro. Why isn’t that the case? I can think of two reasons. The first is that hitters may have a harder time picking up spin direction on high spin rate pitches. This alone might detract from the movement-killing ability of low-spin gyros.

Which brings me to reason number two: There’s no such thing as a pure gyro pitch, a total movement-killer. I told a bit of a fib earlier — gyros only initially spin around an axis parallel to the velocity vector; this ceases to be the case when the velocity vector is no longer parallel to the field. The ball doesn’t travel on a flat path to the catcher due to gravity; the velocity vector will begin to veer downward as g-force takes its toll, tilting the orientation of the ball’s face upward without changing the true spin axis. The change in orientation alone converts some of the gyro spin to sidespin, some of the bullet spin to that more befitting a spinning top, resulting in a late change in movement that can be subtle but effective. And higher spin rates will result in larger late bursts.

Smith-Shawver’s slider is in no-man’s land. It is too spin efficient for the drop characteristic of a gyro ball and too low spin to generate much late break anyways. Hamilton and Moreta’s low spinners are similar in some ways, yes, but they also benefit from outlier characteristics — Hamilton’s is exceedingly low spinning at 1,514 rpm and Moreta’s has that wrong-way movement — that Smith-Shawver’s simply doesn’t have. On the other hand, it’s not spin efficient or high spin enough to create the horizontal break characteristic of a sweeper or even a traditional slider. If he could make the pitch more of a pure gyro, that would probably up its Stuff+ from its current rating of 91. But the thing is, the slide piece currently rates as his best offering per Stuff+; all of his other offerings have above-average spin efficiencies and below-average spin rates, too. The low-spin, low-efficiency combo works best for a slider, but even there it’s less than ideal.

This suggests that Smith-Shawver gets behind the baseball on all of his pitches and might lack the finger dexterity needed to change that. I’m not sure where to go from here besides an entirely new release point, but an overhaul might be worth it. As it happens, the young Brave is far from a finished product and he might be best served furthering his development in the minors after all.

Alex is a FanGraphs contributor. His work has also appeared at Pinstripe Alley, Pitcher List, and Sports Info Solutions. He is especially interested in how and why players make decisions, something he struggles with in daily life. You can find him on Twitter @Mind_OverBatter.

I’ve mentioned this in a couple of different forums. While I remain convinced of AJSS’s upside, I think he just has yet to learn how to pitch at a major league level. He is only three years removed from committing to baseball over other sports, and has really only been focused on pitching for that same amount of time. I wouldn’t be surprised if he has to retool his arsenal a bit in order to be able to to adjust to MLB hitters.