Alek Manoah Brings About Changeups

When the Blue Jays picked up José Berríos at the trade deadline, it wasn’t hard to see the reasoning behind it. Though not without significant cost in the form of two top 100 prospects, the move was clearly an effort to bolster Toronto’s starting pitching in preparation for a potential postseason berth. Berríos is a welcome complement to Hyun Jin Ryu and Robbie Ray at the top of the rotation, but he isn’t the only noteworthy addition to the Blue Jays’ starting pitching in 2021.

Alek Manoah was called up to make his major league debut earlier this season, continuing a fast-tracked professional career that has required him to adapt quickly at every step. The righty was something of a late bloomer, attracting little attention until developing into an elite prospect at West Virginia, eventually going in the first round of the 2019 draft. He made six starts at Low-A in 2019, and impressed the organization enough at the alternate sight in 2020 to begin this season at Triple-A. Even more improbable than skipping both High- and Double-A entirely is that it only took a polished showing at spring training and three starts at Triple-A to convince management that he was major league ready.

Unlikely as it may seem, Manoah’s expedited trip to the majors was backed up by his numbers. In 18 innings at Triple-A this year, Manoah struck out 27 and walked only three, while allowing one run on seven hits. He issued four hit-by-pitches during that time (three came in his first game of the season), which is high, but is also likely an ironic byproduct of the same mechanics that make him so effective. Manoah works exclusively from the stretch, and when he lunges toward the plate during his delivery, he lands toward the third base side of the rubber – an awkward look for a big-bodied righty. While this cross-body motion does an exceptional job of hiding the ball, especially from right-handed hitters, when he doesn’t manage to fully whip his arm across his large frame, he has a tendency to miss arm-side, and given that top-notch deception, hitters tend not to have time to react quickly enough to get out of the way. Aside from that explainable HBP spike in those three starts, he showed virtually no signs of the growing pains you might expect from a guy who skipped two levels of the minors.

He went on to dazzle in his major league debut, holding the Yankees to two hits over six scoreless innings, striking out seven, and walking only two. As was the case throughout his development, he showcased his stellar slider, mixing it well with his fastball, and messing with hitters’ timing. Here’s how those offerings looked in the first inning against Aaron Judge, the third batter he faced in his big league career:

Of particular note in his debut was his effective use of his changeup, a pitch that was a central developmental focus during his time at the alternate site last year. In that first start against the Yankees, he threw his changeup 15% of the time, to hitters on both sides of the plate, inducing a CSW of 31% on the pitch.

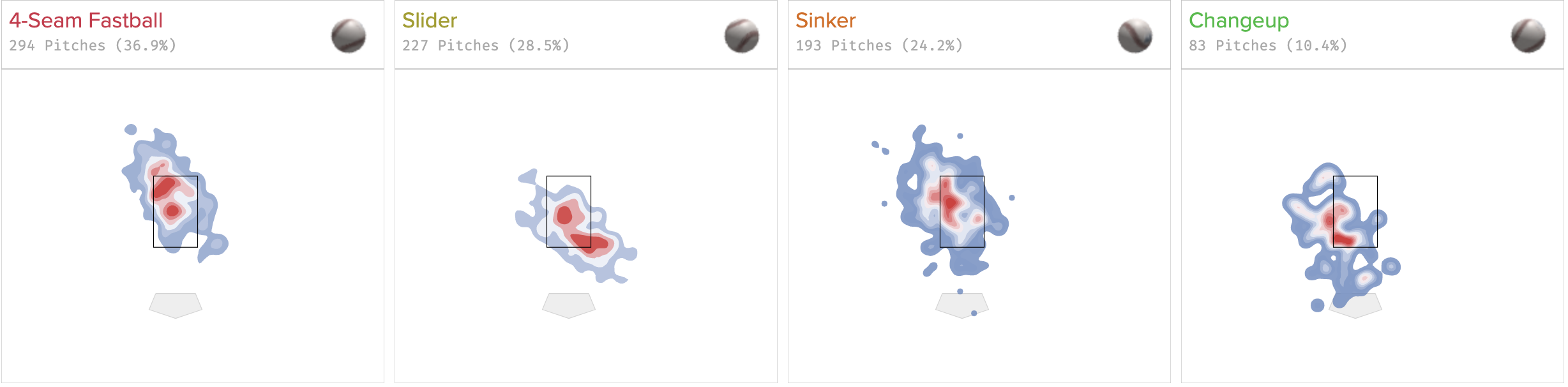

By working his changeup into the mix, he’s able to maintain his steady slider usage (roughly 30% of his overall mix), without resorting to pushing the combined usage of his four-seamer and sinker over the 60% threshold. His slider has extreme horizontal movement, looking like a frisbee to hitters on both sides of the plate. Since it dives in on the back foot of left-handed hitters, Manoah aims to contrast it with fastballs (both four-seamers and sinkers) high and outside, creating a diagonal profile that forces batters to stay weary of both extreme corners of the zone. When the changeup is added to that mix, it pulls the lower outside corner into play, further keeping left-handed hitters off balance.

When he’s not confident in the changeup, or it’s not missing the required number of bats, it opens up the possibility for advanced hitters to either lay off the slider, and sit on the fastball, or vise versa. This of course assumes that the hitter can correctly guess Manoah’s sequencing, which is never a sure thing, but is quite a bit simpler when they’re not also concerned about that changeup.

| Date | Vs. | 4S% | 4S CSW% | SL% | SL CSW% | SI% | SI CSW% | CH% | CH CSW% | CSW% total | SO | BB | H | R |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5/27 | NYY | 34 | 40 | 30 | 31 | 22 | 37 | 15 | 31 | 31 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| 6/2 | MIA | 45 | 30 | 23 | 18 | 24 | 33 | 8 | 0 | 26 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| 6/9 | CHW | 46 | 24 | 21 | 42 | 24 | 27 | 9 | 13 | 28 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| 6/14 | BOS | 47 | 18 | 31 | 38 | 11 | 20 | 11 | 10 | 24 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 1 |

| 6/19 | BAL | 35 | 38 | 28 | 21 | 25 | 41 | 13 | 11 | 30 | 6 | 1 | 4 | 5 |

| 6/25 | BAL | 45 | 30 | 34 | 39 | 16 | 19 | 4 | 0 | 30 | 6 | 2 | 4 | 1 |

| 7/2 | TBR | 30 | 28 | 30 | 45 | 27 | 45 | 13 | 29 | 41 | 10 | 1 | 3 | 0 |

| 7/9 | TBR | 19 | 35 | 26 | 43 | 45 | 33 | 9 | 13 | 34 | 9 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 7/31 | KCR | 31 | 21 | 31 | 36 | 25 | 27 | 12 | 27 | 30 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

His starts since his debut have varied in their quality. He gave up exactly four hits in all five of his June starts, and struggled to keep opponents off the board, though never to such an extent that a return to the minors seemed appropriate. His two worst outings have both come on the heels of some his best ones, which may mean Manoah would benefit from added rest – a notion supported by the addition of Berríos, and the Blue Jays’ potential to go to a six-man rotation later this season. But regardless of the role fatigue has played, there are patterns emerging from his numbers that may help us understand what factors go into his success.

Manoah’s best starts have been those during which he’s been able to throw his changeup more than 10% of the time, while maintaining a CSW% above 20% on the pitch – a balance he was able to strike in his debut, and again on two occasions in July. By far his best start of the season came on July 2 against Tampa Bay, when Manoah took a no-hitter into the sixth inning. He struck out 10 Rays over the course of seven innings, including seven in a row, allowing three hits while issuing only one walk. His overall CSW for the game was 41%, his best on the year, and he threw his changeup 13% of the time, for a CSW of 29%. Later that month, against the Royals on July 31, Manoah had a 27% CSW on his changeup, which he threw for 12% of his offerings, resulting in no runs on two hits over seven innings. He only struck out four in that game, but that may have had more to do with the opponent – whereas Tampa Bay has the highest team strikeout rate in 2021, Kansas City has one of the lowest.

When Manoah’s changeup isn’t working for him, he’s reacted by replacing it with fastballs, which has resulted in an increase in both hits and runs. In his only other July start, Manoah lasted just 3.2 innings, and while nine of those 11 outs came on strikeouts, they came amidst a flurry of walks, hits, and runs (three of each), as well as two hit batsmen and a bit of shaky defense, for what was ultimately not a great showing, despite the K/9.

Manoah’s changeup will never be anywhere near as jaw-dropping as his slider, but of course, it’s not meant to be. It’s like sprinkling a bit of salt on a slice of watermelon: when it’s executed correctly, it only makes the watermelon sweeter. If Manoah can refine his changeup to the point where it effectively tampers with the timing of the hitters he faces, and further expands the zone he’s working with, the slider that has already provided his fast track to the major leagues will continue to propel him toward a successful career as a starter.

Tess is a contributor at FanGraphs. When she's not watching college or professional baseball, she works as a sports video editor, creating highlight reels for high school athletes. She can be found on Twitter at @tesstass.

Great analysis, very insightful.