Alexis Díaz Has Lost His Job for Real. So It Goes.

Going from Cincinnati to Louisville would’ve sounded like a rip-roarin’ good time to Mark Twain. Riverine navigation, heartland American culture, brown liquor and such. Sounds like a good time to me, too. Probably less so for Alexis Díaz, who got demoted to Triple-A on Thursday morning.

Díaz became one of baseball’s most valuable high-volume, high-leverage relievers the moment the Reds called him up in 2022. And while some of the juice from his incredible rookie season faded, he was still closing games through the end of 2024. Now, in the span of about nine regular-season appearances, Díaz has gone from the top of the bullpen ladder to off that ladder entirely. I don’t know if you’ve ever fallen off a ladder, but trust me, it’s not fun.

An optimist might look at Díaz’s 2025 campaign and point out that across four of his six appearances, he’s allowed only a single hit and no runs. Unfortunately, the other two were so bad you can’t really play the selective endpoints game. Across the entire season so far — a total of six innings — Díaz has allowed eight runs, eight hits, and five walks.

Díaz is currently pulling a Joe DiMaggio: More home runs (four) than strikeouts (three). It’s actually worse than that: Over his last three appearances before the demotion, Díaz allowed four home runs and got just a single swinging strike.

The last straw came on Wednesday, when Terry Francona put Díaz into a game the Reds were trailing 1-0 in the top of the ninth. Not a terribly high-leverage situation, but an important one: Blanking the Cardinals in the top of the inning would allow the Reds, who had the middle of the order due up in the bottom of the ninth, to tie the game with a swing. Even if Díaz allowed one run, Cincinnati would’ve still been in position to mount a comeback.

Instead, the Cardinals batted around and plated five runs on back-to-back-to-back home runs. The Reds would probably still have lost no matter what Díaz did, but not even getting a chance there is the kind of thing that eats at a team with playoff aspirations.

In contrast to some other struggling pitchers, the sources of Díaz’s woes are obvious. He’s always had what I’d call a very closer-y walk rate. You know the stereotypical all-gas, no-brakes relief ace who’s only kind of heard of the strike zone but gets away with it because he never lets anyone put the ball in play? That’s what Díaz did his first year or two in the majors. As a rookie, he struck out 32.5% of opponents and allowed a .129 opponent batting average; do that and nobody will care if you walk a batter an inning.

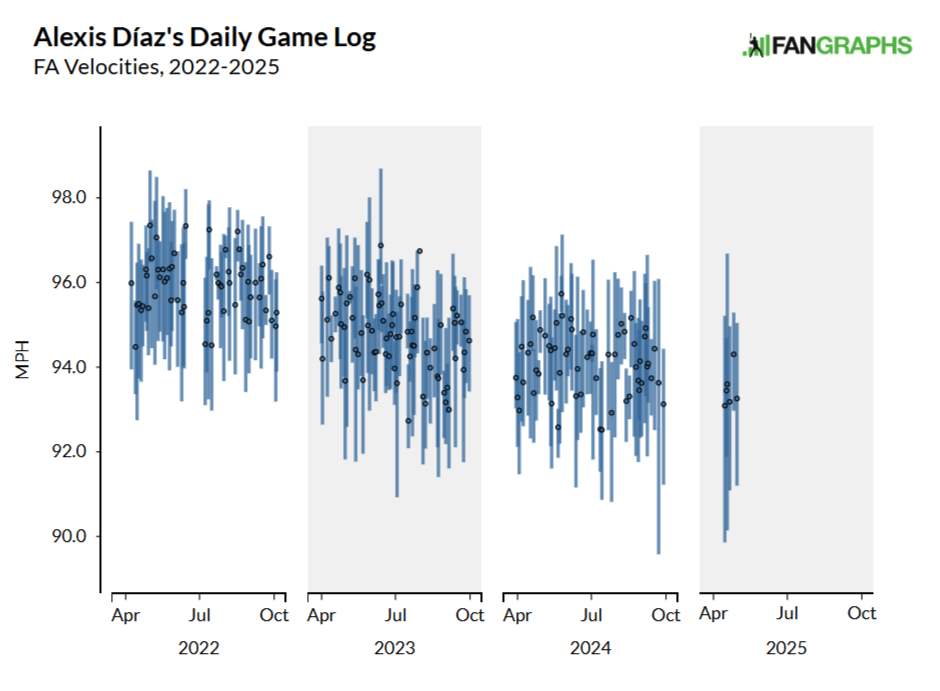

But if the strikeouts dry up, it can get ugly in a hurry. Which leads to problem no. 2: Díaz averaged 95.8 mph on his fastball as a rookie. In six appearances this year, it’s down to 93.3. That’s problematic for the obvious reason: These days, every schmuck on a 40-man roster can put 93 down the pipe in the seats. And it’s worse than that, because with no corresponding decrease in slider velocity, Díaz’s pitches are all coming in around the same high-80s-to-low-90s velocity band. It’s like batting practice out there.

This untimely crisis puts Díaz and the Reds in an awkward position regarding his overall career path. Díaz finished last year with exactly three seasons of service time, which put him in arbitration for the first time.

Closers get paid in arbitration, and Díaz came into his first hearing with a good case. He registered 75 saves across his first three major league seasons; only 12 other pitchers across all of major league history can say the same. The only two other active pitchers with 75 or more saves in their first three big league seasons are Craig Kimbrel and Díaz’s older brother Edwin.

It’s rarefied air, and it got Díaz a $4.5 million contract from the Reds. Even as a relatively inexperienced reliever, he’s Cincinnati’s third-highest-paid arbitration-eligible player. And remember, service time stops if a player is demoted, so if Díaz doesn’t fix himself and get back to the majors in the next couple weeks, it’ll push his free agency clock back a year.

In ordinary circumstances, a touchy pinko like me, with a long history of griping about service time manipulation, would be up in arms about such a thing. In Díaz’s specific case, however, I’m not the least bit worried about when he’ll hit free agency. If he doesn’t get his fastball back and start missing bats again, he won’t make it there at all.

Given that Díaz started the season on the IL with a hamstring injury, perhaps there’s an argument that he should be going back there first. But this decline, in both velocity and results, has been going on for a year now.

It’s a huge drag to see Díaz go down like this, but anyone who wasn’t at least open to the possibility of this happening was delusional. Díaz is one of 11 relievers who’s hit the following markers across his first two major league seasons: 30 total saves, ERA of 2.75 or lower, K% of 27.5 or higher.

| First Two Years | Next Four Years | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Player | SV | K% | ERA | SV | K% | ERA | WAR |

| Craig Kimbrel | 47 | 42.4% | 1.75 | 178 | 40.7 | 1.58 | 9.0 |

| Félix Bautista* | 48 | 40.4% | 1.85 | 5 | 28.9 | 2.00 | 0.3 |

| Dick Radatz | 47 | 29.2% | 2.10 | 70 | 23.8 | 3.57 | 2.9 |

| Troy Percival | 39 | 33.7% | 2.13 | 132 | 27.7 | 3.83 | 3.6 |

| Jhoan Duran* | 35 | 33.2% | 2.15 | 25 | 28.2 | 3.24 | 1.4 |

| John Rocker | 40 | 31.9% | 2.37 | 48 | 27.6 | 4.22 | 1.4 |

| Neftalí Feliz | 42 | 28.5% | 2.42 | 45 | 20.4 | 2.61 | 1.5 |

| Alexis Díaz* | 47 | 31.2% | 2.47 | 28 | 21.1 | 4.76 | -0.3 |

| Roberto Osuna | 56 | 28.1% | 2.63 | 99 | 28.6 | 2.84 | 5.9 |

| Camilo Doval* | 30 | 29.6% | 2.66 | 67 | 28.9 | 3.65 | 2.2 |

Kimbrel had the good sense to get wobbly after he exited the jurisdiction of this table. But Radatz fell apart quickly, and small wonder why: In 1964, his third season in the majors, he led the league in saves and also went 16-9 across 157 innings. He never posted a league-average ERA again. Rocker and Osuna were both finished in the majors after season no. 6, though in both cases that had to do with personal and moral defects as much as professional ones.

Even Percival, who’ll go down as one of modern baseball’s most productive closers, had some rocky years in his late 20s.

It’s frustrating for Díaz, who in a best-case scenario is out his closer’s job and a couple million dollars. The Reds, meanwhile, are probably not thrilled that they’ll have to chase down the Cubs while their would-be closer is in Kentucky finding himself.

More generally, this should be a cautionary tale for fans across the league. The bullpen is the most-scrutinized and least-predictable part of a major league baseball team. Failures elsewhere on the squad might be more costly to the operation as a whole, but they could come anywhere within a game or even go unnoticed. If a reliever blows a game, you’ll know about it. It’s a demanding, thankless job, pitching in relief. Makes you understand why so many pitchers prefer to start.

Díaz’s multi-year collapse is yet another reminder, if we needed one, that the mythical never-blows-a-save reliever simply doesn’t exist, especially on a multi-year timeline. Even as we learn about pitch design and technique in minute detail, the biggest eggheads in baseball still have not figured out how to build a reliable reliever.

Stressful, isn’t it? Twisting and squirming like the proverbial spider dangling over the fire, knowing that even a dominant closer could lose it the next day. Better get comfortable among the peril, my friends, because it isn’t going away.

Michael is a writer at FanGraphs. Previously, he was a staff writer at The Ringer and D1Baseball, and his work has appeared at Grantland, Baseball Prospectus, The Atlantic, ESPN.com, and various ill-remembered Phillies blogs. Follow him on Twitter, if you must, @MichaelBaumann.

While you mention his elevated walk rate, I’m surprised you don’t mention his suspiciously low home run rate in those two elite seasons. Diaz has never gotten many ground balls and plays in the most home run friendly park in baseball. In those two years he recorded the 2nd and 4th lowest single-season HR/FB rates among Cincinnati pitchers since 2016. Now maybe a good bit of that was skill, but there was always some very evident downside there. Even if his stuff didn’t decline, any regression in the home run rate was going to make him more of a good reliever than an elite one given the walk rate.

It’s one thing in particular that’s pretty easy to pinpoint. He’s lost the ability – seemingly, perhaps he never really had it – to pitch to LH batters and to be effective at home, despite not having a specific HR problem at home compared to the road. Never the prototypical command artist, last year he walked 7.5 guy per 9 vs. LH hitters in 114 PA, 2.87 vs. RH. in 128 PA. His season was salvaged by allowing an unrepeatable LD rate vs. LH under 13% (24.7% vs. RH).

At home his walks were up, BABIP was up, K’s were down and LOB% was way down.

Feels like the home splits were more fluky, though it’s still not a great pitching environment.

The L/R splits, however, are much more concerning. SSS caveat applies, but his 13.50 BB/9 vs. LH hitters this year is untenable. He’s faced 16 LH batters, given up 3 HR, and walked 4 of them, vs. 1 HR and 1 BB vs 17 RH batters. The only ‘redeeming’ skill he’s had this year is a low BABIP, but that’s partially due to the over 12% of guys hitting it to the fans, and his wildness (2 hbp vs. RH so far).

There’s other concerning factors – everything off him is in the air, and that’s not a trait you want in Cincy, for instance. But I think you need to start with his ability to pitch to LH batters. Unless he fixes that, there is no viable path for him to pitch in MLB again. This is a guy who was better against LH than RH in 2023 by every measure but a slightly lower BABIP. But he walked less, struck out more, and gave up fewer HR in 144 PA vs. LH (142 vs. RH on the year).

He simply can’t be allowed to pitch in competitive games while he’s facing ~50% LH batters. His OPS vs. LH last year was .738, and that was luck-based driven by that low LD rate. It’s 1.667 this year.

SSS be-damned, there is something there, and it’s horrific. Regression isn’t enough, he needs a technique change, starting with the ability to find the zone against LH batters. Then worry about his batted ball data and quality of pitches. But either way, he needs to get back to basics, and it doesn’t look like this is a one or two week fix. He’s broken.