Financially savvy or cheap? Like beauty, the fundamental essence of thriftiness lies in the eye of the beholder. In truth, either adjective adequately describes the Blue Jays under the stewardship of club president Mark Shapiro and general manager Ross Atkins. In their teardown, the Jays have done much to rebuild the farm system and add a youthful vigor to the big league team. Recent trades to unload veteran talent, most notably the Kevin Pillar and Marcus Stroman deals, were difficult but justifiable moves for a team unable to compete in the short term.

But the Jays have also come under criticism for leaning a bit too far into the rebuild. They were all set to play the service-time manipulation game with Vladimir Guerrero Jr. (a hamstring injury allowed them to delay his call-up without resorting to that tactic) and have been so aggressive in culling their veterans that Anthony Alford, with all of 59 career plate appearances to his name, is now the club’s longest tenured player. The makeover led an obviously delighted Shapiro to gush: “The combination of young talent along with the lack of future commitments, it will never be this again. It’s just for this moment.”

Surprisingly soon after achieving that spiritual high, the Jays started adding major league players. The big signing was Hyun-Jin Ryu, but they’ve made other moves to fill out their hollow roster. The additions of Chase Anderson and Tanner Roark give them a respectable rotation, and by signing of Travis Shaw, Toronto may well lengthen the middle of the lineup. Taken together, these moves make the Jays quite a bit better in the here and now. I don’t know if I’d call them playoff contenders quite yet, but it’s been a far more expeditious winter north of the border than many anticipated.

Shaw signed a one-year contract for $4 million, with incentives that could carry the deal to nearly $5 million if he plays well. Of course, he was only available for that price because he was non-tendered by Milwaukee after his horrible, no good, very bad 2019 season. After producing 3.5 wins in 2017 and 2018, his production fell off a cliff:

Mind the Gap

| Year |

BA |

OBP |

SLG |

HR |

K% |

BB% |

wRC+ |

| 2017 |

.273 |

.349 |

.513 |

31 |

22.8 |

9.9 |

120 |

| 2018 |

.241 |

.345 |

.48 |

32 |

18.4 |

13.3 |

119 |

| 2019 |

.157 |

.281 |

.27 |

7 |

33 |

13.3 |

47 |

For a player who was only 29, the regression was as surprising as it was dramatic. Few players pumpkin overnight and the ones who do usually aren’t in their 20s, nor holding their own at a demanding defensive position.

Knowing nothing else, signing Shaw makes sense for a rebuilder like Toronto, particularly given the terms. It’s a classic pillow contract, a one-year, low-dollar commitment that won’t disrupt the club’s burgeoning young core. A third basemen by trade, Shaw will likely slide across the diamond to first to fill the vacancy left by Justin Smoak’s departure. The new man will get a chance to start and rebuild his value after a nightmare season, a mutually beneficial proposition; if last season proves an aberration, the Jays can flip Shaw for a prospect near the deadline. For his part, Shaw would then hit free agency without his 2019 numbers looming over his recruitment.

The challenge here is that Shaw didn’t merely have an off year, or put up lousy numbers after battling an injury. Rather, he was simply one of the worst players in the league last season. Among players with at least 250 plate appearances, only Mike Zunino offered less at the plate:

Lowest wRC+ in 2019

200 PA Minimum

Everywhere you look, there’s a damning statistic. He struck out in 33% of his plate appearances, which is troubling on its own and also nearly double how often he fanned in 2018. His .157 batting average was the lowest in the league, which is bad, though not nearly as bad as the fact that his .270 slugging percentage also brought up the rear.

But a glance at Shaw’s batted ball profile suggests that all may not be lost just yet. His average exit velocity has barely budged throughout his major league career, and he actually set a career best in 2019, at 88.7 mph. His hard hit rate was only a tiny bit lower in 2019 than in previous seasons. For what it’s worth, he hit just fine in Triple-A after a midseason demotion.

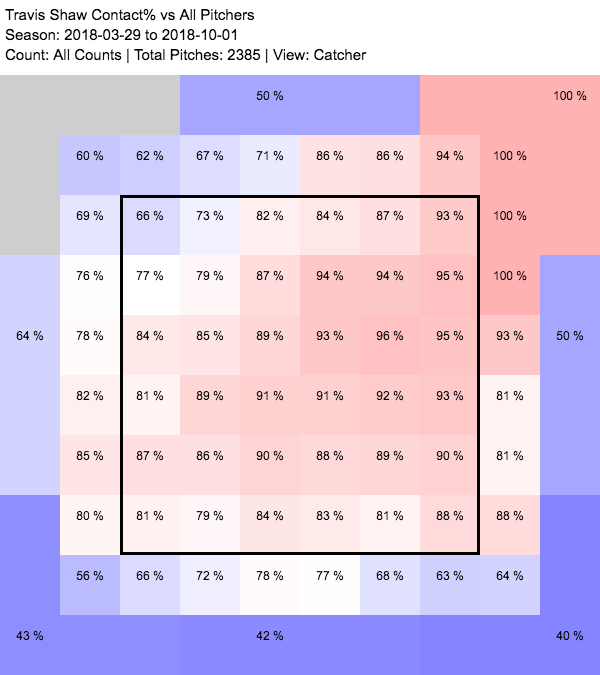

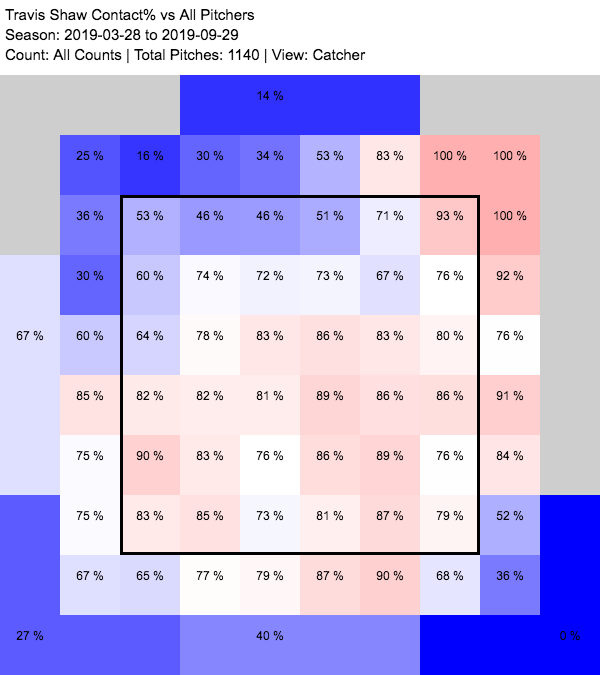

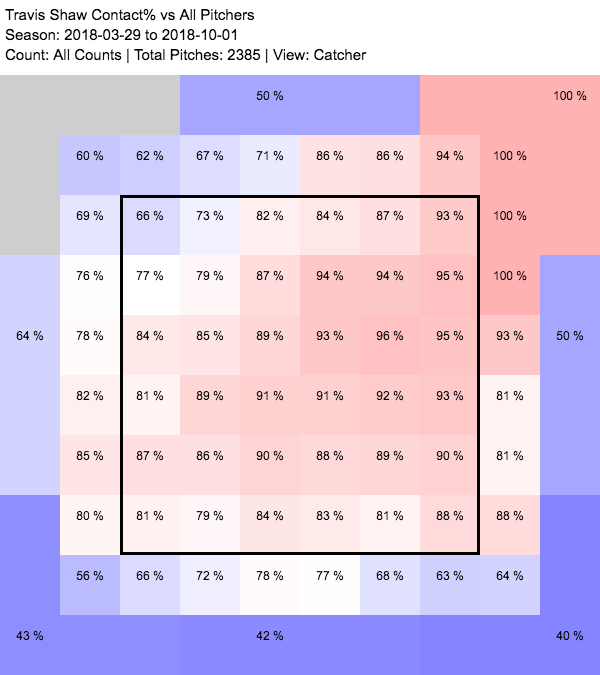

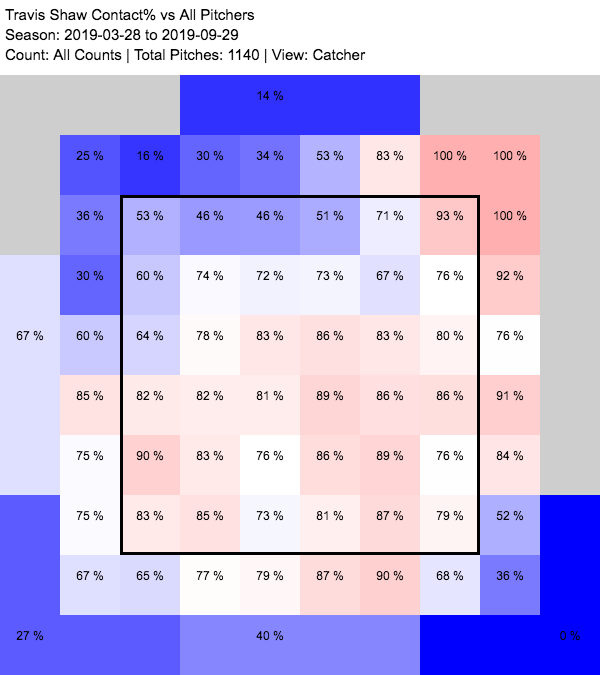

Shaw had two problems last year, and they may well be related. The first is that he swung and missed far too often, and way more than he normally does. He made contact 70% of the time he swung last year, which is bad relative to the league and terrible compared to his career norms. There isn’t a key split here, mostly because none of them are good: He didn’t swing any more often (on either pitches in or out of the zone) but he missed a whole lot more, and his whiff rate rose on fastballs, offspeed pitches, and breaking balls. The uptick in missed fastballs was particularly substantial, from 18% of the time in 2018 to nearly 30% last year. Interestingly, a lot of those increased whiffs were concentrated in the upper part of the strike zone and above. His whiff rate was worse just about everywhere, but the difference is especially glaring above the belt:

That feeds into the second problem, which is what happened when he did connect. Always a guy who put the ball in the air a lot, Shaw’s average launch angle shifted from 16.6 degrees to 24.5 degrees (the league average was 11.2) in 2019. That was the second highest launch angle in baseball, and as you’d expect, it produced a corresponding increase in fly balls and popups from previous campaigns.

Critically, this change was clearly counterproductive for Shaw. On this site, we’ve often covered how hitters try to change their launch angle in an effort to hit more balls in the air, and how this tends to lead to a better offensive output. But there’s a limit to how high you want to go. It’s not necessarily that Shaw climbed into dangerous territory — Rhys Hoskins had the third highest launch angle last year, and Edwin Encarnación and Mike Trout occupied similar real estate — but it may well be dangerous territory for him. After all, Shaw was a pretty darn good hitter pre-2019, and with a higher launch angle than most bears. Raising that launch angle produced more harmless flies and far more swings and misses, particularly up in the zone, as we’d expect from a player using a steeper swing plane. All of this suggests that he wasn’t getting his bat in the hitting zone for nearly long enough.

It’s a trend that started early in 2019. At FanGraphs, we’ll often talk about how spring training numbers are meaningless, and usually they are. At the very outer fringes of the extremes though, we can sometimes detect something meaningful, for either good or ill. Such was the case with Shaw last year, who struck out 25 times without a walk in 52 trips to the plate. He hit the ball pretty well when he did connect last spring, which somewhat masked the issue at the time, but in hindsight it’s clear that this was a season-long problem for him.

Despite the depths of his struggles, this seems like a reversible trend. It’s far easier to fix glaring and identifiable problems than to grasp for solutions in the dark. Toronto’s challenge is to either help Shaw make more and better contact with the swing plane he employed in 2019 or to help him return to what worked in previous seasons. Simply knowing what to do doesn’t ensure that Shaw can do it, of course, but at least it’s a theoretically fixable issue. We’ve seen plenty of players successfully adjust their launch angles and there’s no reason to think Shaw can’t do the same.

Ultimately, for one-year and $4 million, this is the kind of move rebuilding clubs should be lining up to make. If Shaw doesn’t hit, the team can swallow the money and find someone else to man first base. But even modest improvement makes this a bargain of a contract, and given Shaw’s underlying batted ball indicators and recent history of success, there are plenty of reasons to think he can bounce back. A return to form won’t necessarily propel Toronto to the top of a very competitive AL East, but combined with a number of promising young players, it would go some way toward making the Blue Jays a fun club to watch in 2020. Between that and his potential re-sale value, what’s not to like?