If you take a quick glance at Aaron Civale’s 2021 numbers, nothing looks out of the ordinary. Yes, the 2.18 ERA signals a stellar start, but with strikeout and walk rates relatively in line with his career numbers, you wouldn’t suspect that Civale has undergone a host of changes to both his repertoire and his delivery. But look beyond the numbers to the guy on the field, and it’s clear that he’s undergone a rather obvious change in his process and approach, one that merits further analysis.

Coming into the season, Civale was mainly a sinkerballer, though that requires a rather liberal definition of the word “mainly.” Civale threw his sinker, cutter, and curveball to batters of both handedness, and supplemented those main offerings with a side of slider to righties and a side of changeups to lefties. That mix of speeds and movements put him in an interesting class of pitcher:

Five Frequent Offerings

| Pitcher |

FIP |

WAR |

| Yu Darvish |

2.23 |

3.0 |

| Hyun-Jin Ryu |

3.01 |

1.8 |

| Max Scherzer |

3.46 |

1.8 |

| Aaron Civale |

4.03 |

1.2 |

| Kyle Freeland |

4.65 |

1.0 |

| Mike Fiers |

4.94 |

0.6 |

| Danny Duffy |

4.75 |

0.6 |

| Johnny Cueto |

4.64 |

0.5 |

| Adrian Houser |

4.82 |

0.4 |

| Jon Lester |

5.14 |

0.2 |

| Tyler Alexander |

5.26 |

-0.1 |

| Alex Young |

5.57 |

-0.2 |

| Tanner Roark |

6.86 |

-0.6 |

| Total |

4.41 |

10.3 |

Pitchers with five pitches thrown at least 100 times, 2020

As you can see, Civale was one of 13 pitchers to throw five different pitches at least 100 times last season. This isn’t a group of particularly good or bad pitchers. In fact, combined, these 13 had a FIP- of exactly 100. And though Civale had a solid 2020 season, it’s not as if his 4.74 ERA, 4.03 FIP, and 22% strikeout rate scream ace.

What is interesting about Civale is that he has changed so dramatically year-over-year. Though he threw five different pitches fairly frequently, it is Civale’s sixth pitch — his four-seam fastball — that is in the spotlight so far this season. After throwing just 58 total four-seamers out of a total of 2,064 pitches over his first two seasons in the majors, Civale has already thrown 83 in his three starts this April. Still, that’s not the only change he has made (pun fully intended). Civale has ditched his traditional changeup in favor of a split-change and has all but stopped throwing his sinker. His yearly pitch type chart is extraordinary:

That’s not all. Civale also completely revamped his delivery, adopting a shorter arm action. It’s the same mechanical change Lucas Giolito made going into the 2019 season, greatly contributing to his development into a frontline starter. In a similar move, Civale went from being a long-windup, over-the-top pitcher last season to one who is now a side-stepping short-armer.

“That will be my windup for the year,” Civale told reporters, including Mandy Bell of MLB.com, this spring. “I did a lot of my work out of the stretch in the offseason. Changing my arm path, I didn’t want to add any rotation into my delivery that could alter that. Just decided to keep it simple. I didn’t do too much work on that windup, it’s just a little stutter-step. Not really shifting too much weight. A lot of the work I did to transition to the new arm path was out of the stretch. Less movement is less chance for error.”

Here’s 2020:

And now 2021:

Given how much Civale changed, the title of this article may actually be an understatement. One could argue that he is a completely different pitcher now. It’s hard to know exactly what results those changes will bring, and considering how different he has become, it’s interesting that his numbers are almost identical to last year’s thus far.

Still, it’s worth examining the early returns on an individual pitch level — even if the samples are minuscule — and comparing those to previous seasons. First, let’s look at the exchange of the sinker for the four-seam fastball, a rather common move by pitchers over the last few seasons as sinkers across the league continue to get crushed.

2020 Sinker vs. 2021 Four-Seamer

| Pitch |

% of Total |

MPH |

wOBA |

xwOBA |

Whiff% |

CSW% |

| 2020 Sinker |

28.9% |

91.8 |

.359 |

.358 |

11.3% |

34.0% |

| 2021 Four-Seam |

29.6% |

91.3 |

.293 |

.361 |

31.8% |

25.3% |

Admittedly, the number of both pitches he’s thrown is small. But, at least so far, what is interesting is that the pitches have generated rather similar quality of contact results. While Civale’s four-seamer has performed better from a wOBA standpoint, the two pitches have almost identical xwOBAs. Also striking is that Civale’s CSW% from his 2021 four-seam is lower than on his 2020 sinker, despite generating a whiff almost three times as often. Indeed, Civale already has 14 whiffs on his fastball this season, out of 44 total swings; last year, his sinker generated just 15 whiffs on 133 swings. That is a marketed improvement.

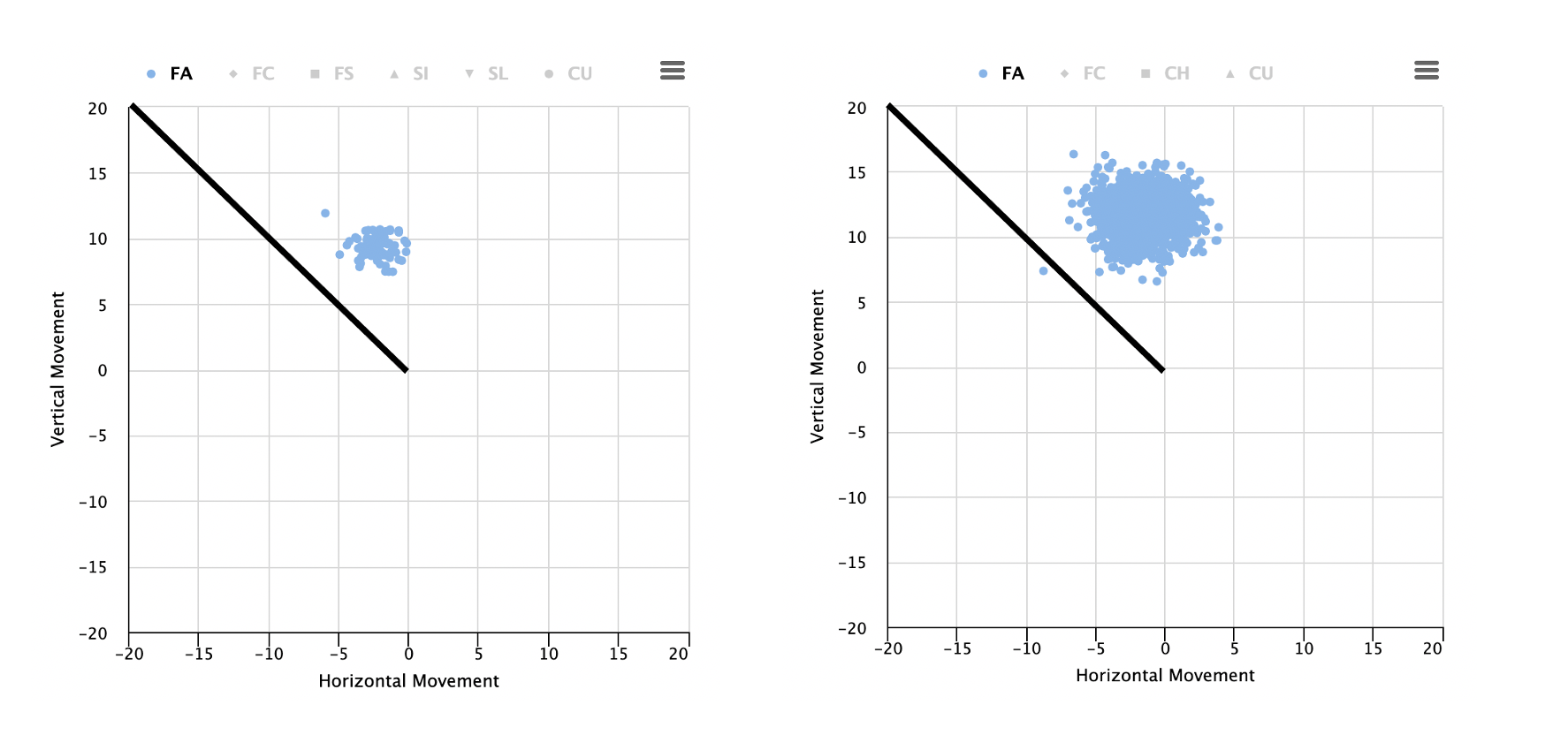

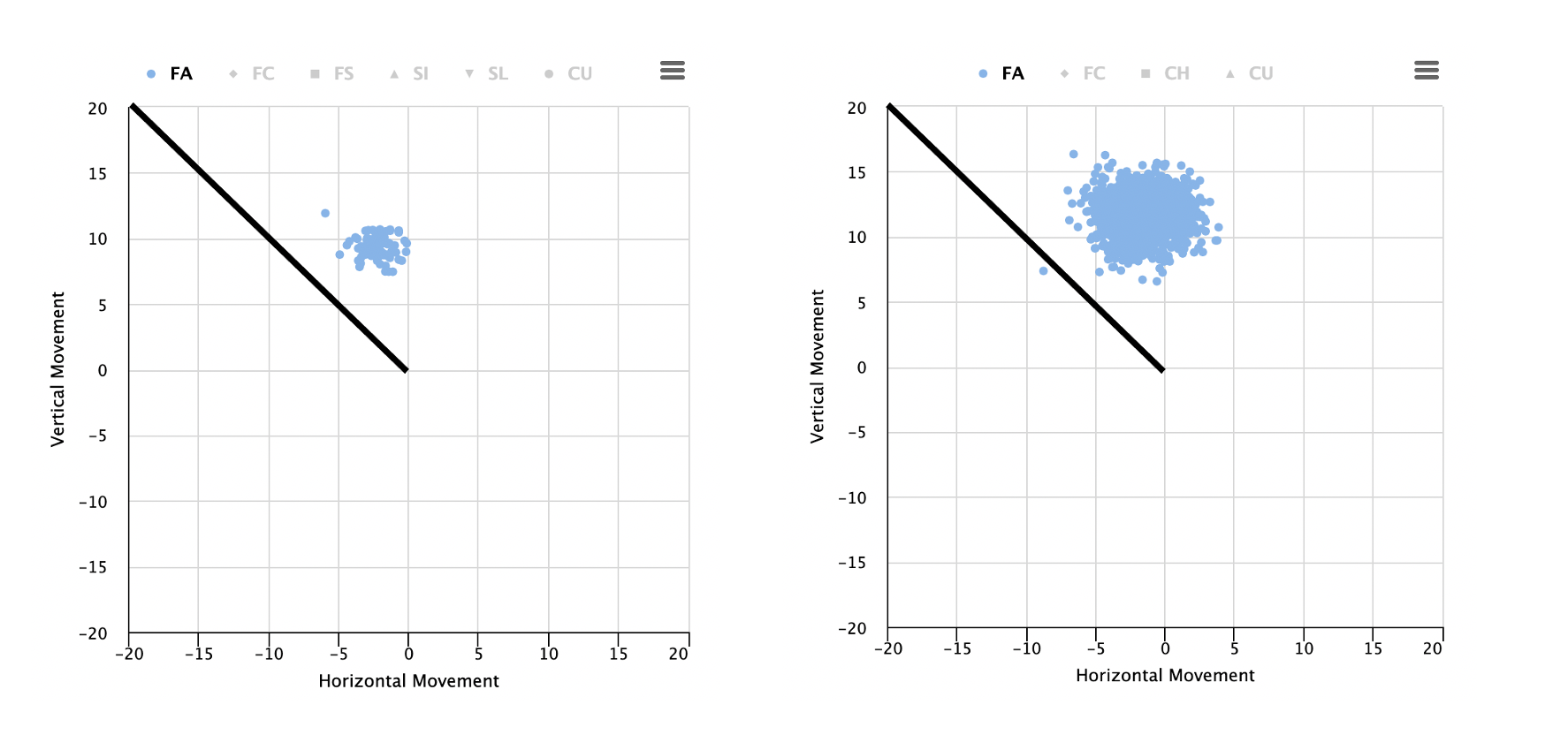

Additionally, while neither Civale’s fastball nor sinker will blow by hitters in the low-90s, the four-seamer’s movement profile is noteworthy. Kevin Goldstein recently wrote about the importance of fastball shape, and indeed, Civale’s pitch looks not-too-dissimilar from the 2016 Marco Estrada example he was highlighted. 2021 Civale is on the left, and 2016 Estrada is on the right:

Of course, Civale doesn’t quite match Estada in the vertical movement department. But there’s clearly a similarity between the two in terms of raw, non-velocity-adjusted rise. Even after adjusting for velocity, however, Civale still generates about 5% more rise on his fastball than average, which definitely represents better pure stuff than his sinker, which generated 8% less sink than average. Indeed, as we would expect, there are signs that hitters will be popping him up. Civale is currently in the 75th percentile in average launch angle off of the four-seam fastball and has also been a big proponent of the lazy fly ball, ranking 16th in average exit velocity allowed on all air contact.

Then there’s the changeup, which — as Civale noted himself — is now a split-change. With the adjustment, it might have become his best pitch, or at least gives him a second strong offering in addition to the cutter. By our pitch values, Civale’s 2020 changeup was worth 1.6 runs above-average per 100 pitches. So far in 2021, his “split” has been worth 4.3 runs per 100. While we are again dealing with small sample caveats, here is what the quality of contact numbers look like year-over-year:

Changeup vs. Split-Change

| Pitch |

% of Total |

MPH |

wOBA |

xwOBA |

Whiff% |

CSW% |

| 2020 Changeup |

9.2% |

85.3 |

.155 |

.272 |

34.1% |

31.8% |

| 2021 Split-Change |

18.2% |

84.6 |

.146 |

.174 |

17.9% |

19.6% |

Again, we can’t yet draw firm conclusions from the wOBA and xwOBA data, though in the early going, it seems as if Civale has made what was a good pitch even better. Similar to the fastball/sinker chart, though, Civale is struggling in the CSW% department, with his former pitch performing much better than his new one so far. It very well could be noise, or it could still be him getting used to the new delivery; it’s worth noting that his overall CSW% is down six points from 2020 to ’21 as well. Nonetheless, to the naked eye, it definitely looks like he is getting more bite on the change; it’s dropping by about four more inches this year on average.

Here’s Civale’s 2020 change:

And here’s his 2021 split-change:

What do we make of all of this? It’s hard to know. There are so many moving parts, and it’s still early in the season, after all. But if you like pitcher reboots, you should definitely be paying attention to what Civale has done. I am not sure I have ever seen a pitcher change so much in just one offseason. I’m curious to see how it works out for him, and, really, I’m fascinated by his willingness to overhaul everything in an attempt to become a more effective player.