The New Ball Is Confusing!

Last week, Justin Choi published an examination of the new ball. The results were — well, you should read it for yourself, but they were muddled, to say the least. Home runs are down! Exit velocity is up! Liners got better, fly balls got worse. It’s enough to make you wonder whether we’ll ever know the answer. It’s also catnip to analysts, and so today I’d like to present some supplemental evidence that only makes me more confused.

There were two key conflicting findings in Justin’s research. First: home runs are down, and fly balls aren’t carrying as far, on average, as they did last year. Second, overall exit velocity is up league-wide, whether you care about broad averages or the hardest-struck balls. The two effects — harder hits, less carry — benefit line drives over fly balls, because line drives both spend less time in the air and depend less on distance for their value.

I wasn’t really sure what to make of the fact that fly balls are carrying less. There are so many confounding factors — weather, new humidors, angle, stadiums, the list goes on and on — that I don’t think I’ll ever be able to disambiguate them all, but I took a crack at it.

First things first: I took all the batted balls that were hit from April 1 to April 30 in 2019. Why 2019 instead of 2020? Temperature and weather are part of the total picture here, and given that there were no April games last year, we’ll have to go further back to make our data tie out.

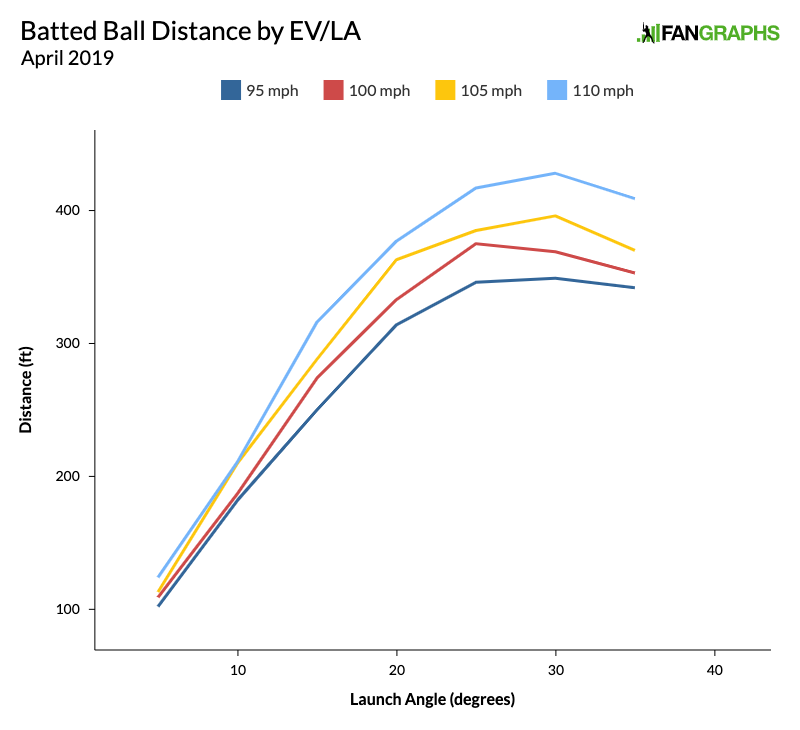

Next, I separated them based on their launch angle and exit velocity. I took every ball hit between 93 and 97 mph and put them in a 95 mph bucket, every batted ball between 98 and 102 mph in the 100 mph bucket, and so on. I then bucketed those batted balls by launch angle in the same way. The result is this graph of hit distance based on launch angle and exit velocity:

Pretty and informative, at least in my opinion. Or, well, partially informative at least. It’s unsurprising that hitting the ball harder uniformly leads to higher distance, but the decrease in distance when you hit the ball too high makes sense, and I’m happy to see that there.

Great, so we have a 2019 baseline. Plenty has changed since then, both in baseball and in the world at large, but it’s a starting point that can be used for comparison. It’s not foolproof — with only a month of data, the sample isn’t overwhelmingly large — but it can at least give us an idea of whether a massive change has occurred.

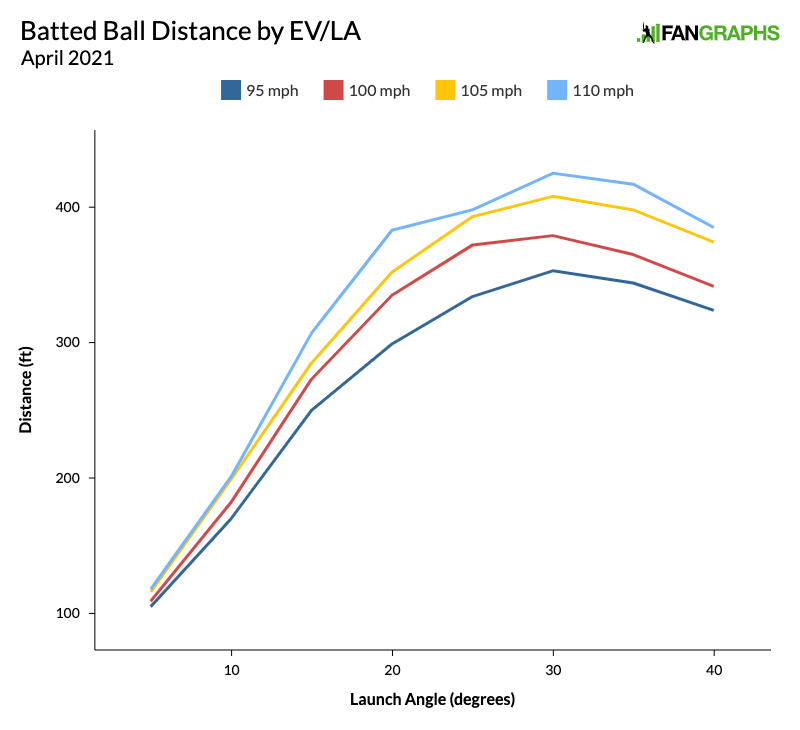

Let’s look at the same data through games of April 12 this year:

Okay, great, those curved lines look similar to the other curved lines. That’s encouraging, in that we didn’t end up in the Upside Down in the intervening two years, but zoomed-out graphs are no way to discern differences.

Let’s instead look at the changes from one year to the next, using a table instead of a graph. Obviously, now that we’re controlling for launch angle and exit velocity, the increased drag will curtail all distances, higher-angle balls more so… right? Well, drat:

| Speed/Angle | 5 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 25 | 30 | 35 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95 | 3 | -11 | 0 | -15 | -12 | 4 | 3 |

| 100 | 0 | -5 | -1 | 2 | -3 | 10 | 12 |

| 105 | 3 | -10 | -3 | -11 | 8 | 12 | 28 |

| 110 | -5 | -10 | -9 | 6 | -20 | -3 | 8 |

That’s a bunch of gibberish. Balls hit at 20-25 degrees, roughly a high line drive, haven’t gone as far. Balls hit at a loftier angle — the ones we expected to be hurt the most — are carrying farther. And balls hit at 10 degrees, low line drives, are also down in distance. This isn’t what I expected at all.

Now is the time where I inject a healthy dose of qualifications. These batted balls aren’t exactly like-for-like. They weren’t all hit in the same stadiums in identical conditions. I’m not accounting for spin on the ball; a little bit of backspin can increase carry, while topspin (or hook/slice) can decrease it. Some of these buckets, particularly in 2021, are light on observations; a wind-aided ball or two could overwhelm the effects of the new baseball.

All that said, I spent some time trying to find reasons to doubt my sampling method and mostly came up empty. When you select every batted ball within 2 mph of a given signpost, you aren’t guaranteed the same average in each sample. I went back and looked — and nope, not a problem. The average within each exit velocity delineation was within 0.1 mph for each observation, and only the 95 mph bucket displayed higher average exit velocity in 2021. Next!

What about launch angle, in the same way? Maybe the “35” degree balls in the 2019 sample are actually 36 degrees on average, while they’re 34 degrees in 2021. Given that more loft past a certain point decreases distance, we could have a problem there. I had marginally more success poking holes in my own graphs there, albeit in the wrong direction. The 110 mph/35 degree bucket, in particular, had 0.3 degrees more average loft in 2021 — but that should point the other way.

In truth, we can’t say much about the new ball based on the data I’m presenting here. If the new ball is changing the carry of balls in flight — and based on what the league said about the ball before the season, there’s good reason to believe that’s the case — a more granular study will be necessary to measure that change in carry.

That change in exit velocity? It’s real — depending on where you look. In 2019, the hardest 20% of batted balls averaged 103.5 mph off the bat. In 2021, that number stands at 103.3 mph. That’s basically indistinguishable, but the top of the register shows some differences:

| Top | 2019 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|

| 20% | 103.5 | 103.3 |

| 10% | 106.4 | 106.6 |

| 5% | 108.6 | 108.9 |

| 3% | 109.9 | 110.2 |

| 1% | 112.1 | 112.7 |

Additionally, as Justin mentioned, hitters are setting new highs in exit velocity left and right. I’m comfortable saying that, at least in the early going, the ball seems to favor higher exit velocities. I’m just not so sure that we can say anything about its drag properties based on batted ball data.

That leaves one mystery. Why aren’t fly balls carrying as far this year? If you’ll recall from Justin’s article, the average fly ball (25 to 40 degrees) carried 334 feet in 2020. In 2021, that number is at 329 feet (up slightly since his article was published). That’s still five feet short, but there appears to be at least some seasonality. In 2019, April fly balls averaged 329 feet of carry. Fly balls for the year as a whole checked in at 332 feet. In 2018, April fly ball distance checked in three feet short of the year as a whole.

That’s certainly not conclusive. Heck, I’ve been using all-April sample sizes to get more data points, but I can’t use all of April 2021 just yet, what with the tyranny of linear timelines. There are all kinds of problems with finding any definitive takeaways from this analysis.

That lack of conclusion is, in my opinion, interesting in itself. I was half-expecting a bright line change, an obvious difference between baseballs old and new. Instead, the difference is subtle, measured in single-digit feet and fractions of a mile per hour — if indeed there has been one so far.

There’s other ancillary evidence that the ball might be suppressing offense. Home runs per batted ball are down from April 2019, as well as from last year. That’s in spite of the fact that, as we already covered, the hardest-hit balls are being hit harder than ever. It sure feels like something’s going on. For the life of me, though, I can’t figure out what it is.

There will be plenty more time to observe the ball as the season wears on. We’ll get more information with every crack of the bat, with every lazy fly ball and smoked line drive. Granular data on the flight of the ball and atmospheric conditions will help, as well. The mystery won’t remain unsolved forever. For now, though, I feel comfortable saying only this: MLB has announced that they are using a different baseball, but there isn’t yet conclusive evidence of that ball’s effect on the game.

Ben is a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @benclemens.

Is there any objective difference in average movement and/or spin by pitch type? Any change in seams would likely show up on both sides–fly ball distance as well as pitch movement. Not sure if it’s possible to get a clean average, given all the types/classes of pitches, though…

It definitely wouldn’t hurt to check on this. However, I think with how intentionally pitchers can manipulate their pitches, with and without substance, and the frequency which they alter their repertoires it could also turn out to be noise.