Can “Hard In and Soft Away” Make Your Troubles Go Away?

I’ve been thinking a lot about two Yankees hitters recently. That’s less common than you’d think for me; out on the west coast, the TV isn’t overrun with Yankees highlights, and there are just so many baseball teams, so many interesting players to ponder. But I heard an announcer discussing one of my favorite baseball tropes, and it brought Giancarlo Stanton and Anthony Rizzo to mind.

“Hard in, soft away” is a pitching adage, and one that makes plenty of sense. There’s a mechanical aspect to it, for one: to hit an inside pitch on the barrel, a hitter has to rotate more, which naturally takes more time. On the other hand, a slow pitch has the best odds of eluding a batter’s swing, or at least the most dangerous part of the bat, if the hitter swings too quickly; in a regular swing, the barrel gets to the outside part of the plate first (on a plane to hit the ball the other way) before rotating around to the inside of the plate (on a plane to pull).

I’m not a hitting mechanics expert, and that doesn’t describe the whole story. The batter could pull his hands in to try to get the bat head through the zone more quickly, or employ different swings for differently located (or angled) pitches, or any number of counters. But the default assumption – batters want to get the bat around on inside pitches, so pitchers should give them less time to do that, and vice versa – is at least a decent approximation of the physical reality in play.

There’s another benefit, too. Think of a righty pitcher facing a righty batter. Aim right down the middle, and a fastball will naturally drift inside, while a slider or curveball tends to head down and away. Take a look at this overlay GIF, by everyone’s favorite lawyer-turned-internet-baseball-personality Rob Friedman:

Michael King, 97mph Two Seamer and 83mph Breaking Ball, Individual Pitches + Overlay pic.twitter.com/uyRutUt2QU

— Rob Friedman (@PitchingNinja) June 25, 2022

That’s how fastballs and breaking balls play off of each other: with the fastballs finishing in and the breaking balls away. Imagine what a slider paired with this outside fastball would look like:

It would bounce in the opposite batter’s box, and it’s hard to get a swing if you’re that far away. Likewise, imagine the fastball that would pair with this inside slider:

That would be a hit by pitch, or perhaps behind the hitter. I’m not saying that pitchers never throw fastballs away or breaking balls in – I just showed two examples of that – but you can see why that natural pairing exists. It’s not quite as obvious with opposite-handed batters – pitchers tend to go to changeups, which finish away, but how they pair offspeed pitches with fastballs isn’t quite so rote – but in general, hard in and soft away really does reflect how baseball works.

Want the numbers? Of the pitches thrown at least three inches towards the righty batter’s box from the middle of home plate – inside pitches, but with a strict formal definition – in righty-righty matchups this year, 67% have been fastballs. Only 47.3% of away pitches – at least three inches toward the lefty batter’s box from the center of the plate – were fastballs. It’s a real effect, and again, it’s quite clear why.

This means a few things. First, batters do better against inside pitches, because they do better against fastballs. It’s not quite that simple – batters perform better against inside fastballs than they do against outside fastballs – but the central idea is quite true. I’ve been guilty of this in the past; if you don’t control for what type of pitches batters are most likely to see, you’ll get some strange and spurious inside/outside results.

More meaningfully, pitchers mostly don’t throw breaking balls inside. They throw their fair share of fastballs away – there are just more pitches away than pitches inside, a trend that has long been true – but if you’re going to come inside, it almost has to be a fastball. Can you imagine floating a slider onto the inside corner against Mike Trout? He’s going to be out in front of it, and that’s exactly where he wants to be, putting the barrel of the bat on a soft pitch he can obliterate. Righty batters produce a wOBA nearly 90 points higher when they put an inside breaking pitch into play as opposed to an outside one. That’s the equivalent of the difference between Pete Alonso and Randal Grichuk. Here’s my valuable tip to pitchers: more Randal Grichuk, less Pete Alonso.

Hitters can take advantage of that fact, though. If you set up in a way that dares pitchers to throw inside, you’re manufacturing a situation where you’ll see an abnormally high number of fastballs. Pitchers don’t like to throw breaking balls inside. They know the rule: you want more Grichuks and fewer Alonsos. But it’s a false dichotomy, because if you’re coming inside anyway, the choice isn’t between a breaking ball in and a breaking ball away; it’s between a fastball in and a breaking ball in.

Plenty of pitchers don’t like to throw breaking balls inside, and you could easily imagine them being uncomfortable with doing so. Let’s go back to our Yankees from the introduction. Giancarlo Stanton faces the second-highest rate of inside pitches among all right-handed hitters. I speculated that it might have to do with shifts; plenty of readers noted his closed stance, which is undoubtedly part of it as well. His front shoulder is turned so far inward that his turning on a well-placed fastball seems impossible.

If you’ve watched Stanton play, you know that it’s not impossible. When he makes contact with an inside fastball – and he makes plenty of contact with fastballs overall, everyone does – he’s posted a blistering .488 wOBA over the past seven years. In other words, he crushes fastballs, which I’m sure you already knew, because you’ve taken one look at the most powerful hitter in the game.

Pitchers should really throw him more breaking balls and offspeed pitches, out of self-preservation if nothing else. He’s worse against them! He’s more likely to swing and miss against them, and getting a swing and miss is pretty much the only way a pitcher can face Stanton and not fear a 120 mph rocket.

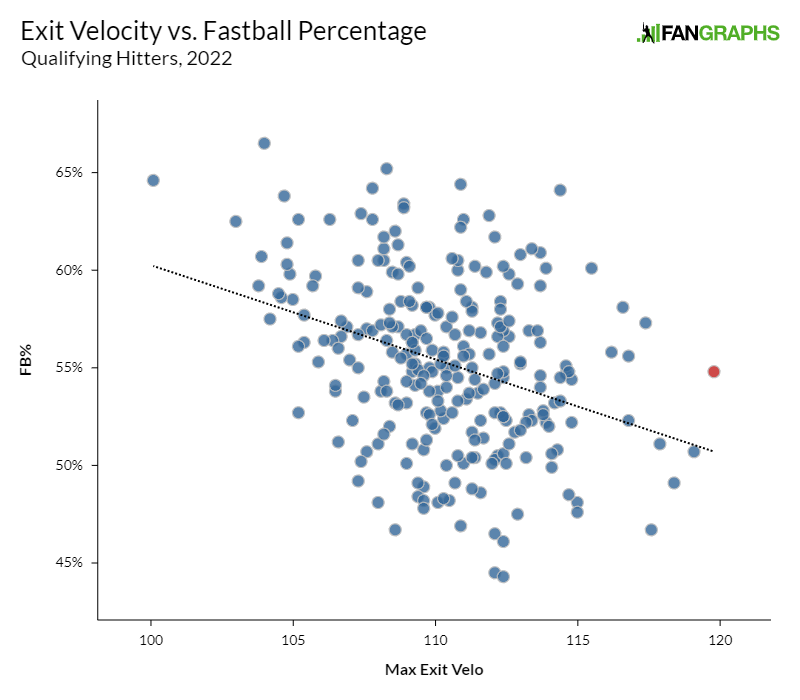

Here’s a chart of maximum exit velocity against fastball rate. The harder you can hit the ball, the fewer fastballs you see. If you’re a fastball hitter, like nearly every hitter in the game, you want to live above the downward-sloping line. Plenty of hitters do, but it’s a particular surprise to see Stanton there. He’s the red dot on the right:

What’s a pitcher supposed to do? The obvious thing to do against Stanton is throw inside. But when your catcher calls for an inside slider, you’ll probably be inclined to shake him off. Righty pitchers have thrown three times as many secondary pitches outside as inside this year. That’s the pitch they’re comfortable executing. Hard in and soft away, remember?

If you’re a powerful hitter, I think you should copy Stanton’s gambit – and to a lesser extent Rizzo’s, though I haven’t focused on lefties in this article. Set up in a way that dares opponents to throw inside. Make it so they can’t help but come inside. Force the issue. Close your stance off, or crowd the plate, or otherwise set up in the batter’s box with an eye towards covering pitches on the outer third of the plate. As an added bonus, if pitchers won’t come inside – and as we’ve learned, righties like to work outside to righties – you’re better set up to hit those prevalent outside pitches. It’s a win-win situation.

Maybe it won’t work. I’m not sure how absolute pitchers’ resistance to inside secondary pitches really is. Maybe they’re happy to throw them, but choose not to for some reason I haven’t yet divined. Maybe hitters would just do so much damage when they connected with those pitches that the whole equation wouldn’t work, even though the data we have suggests that’s unlikely.

But you won’t know unless you try, and as best as I can tell, the most prominent player to try this strategy is profiting handsomely. Why not try what Giancarlo is trying? It seems to have worked for him, and anything that can get you more fastballs in this age of unhittable secondaries is well worth investigating.

Ben is a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @benclemens.

Stanton’s last six hits are home runs that mostly look like they should be pop ups. But I also don’t think anyone (besides Judge? And new young Cruz?) can do what he does, so…

Ohtani, Vladito, and Yordan Alvarez are all in the same EV bracket.

I wish the Statcast page (somewhere, on some site) had something like a 90th percentile EV instead of max EV. Reduces the chance that it’s due to measurement error.

But also yes, Stanton and Judge are probably in a class of their own. Both have hit balls over 121 MPH. the only other guy to do that since 2007 was Gary Sanchez, and the rest of his metrics aren’t even close to Judge and Stanton. There are plenty of other guys with high max EV’s too including Machado, Yordan Alvarez Alonso, Trumbo, Ohtani, Nelson Cruz, Vlad Jr, Gallo, and Sano…but I don’t think any of them are like Judge and Stanton.

Even Judge is not like Stanton, to be honest. Giancarlo is in his own level when it comes to natural power.