Carlos Santana’s Encore Features New Material

Author’s note: Five Things will return next week. In the meantime, enjoy an article about one of my favorite players.

Do you want to know how much Carlos Santana loves playing baseball? From 2020 through 2023, he played for five teams, got traded midseason twice, and compiled a 94 wRC+. He was 37, had earned more than $100 million in his career, and didn’t have an obvious everyday starting job lined up. He could have hung up his spikes right then – but he took a one-year, $5.5 million deal with the Twins and turned back the clock with a 114 wRC+. Then he signed another one-year deal, this one for $12 million with the Guardians, and kept the train rolling. Through the first third of the season, he’s on pace for his best year in more than half a decade.

What’s his secret? As a fellow 39-year-old, I wanted to find out – for, you know, mostly professional reasons, but also because sometimes my knees hurt after going on a particularly brisk walk. Bad news for me, though. I’ve found out one thing that Santana has done in 2025 to rejuvenate himself, and I’m not sure that I can replicate it in my personal life.

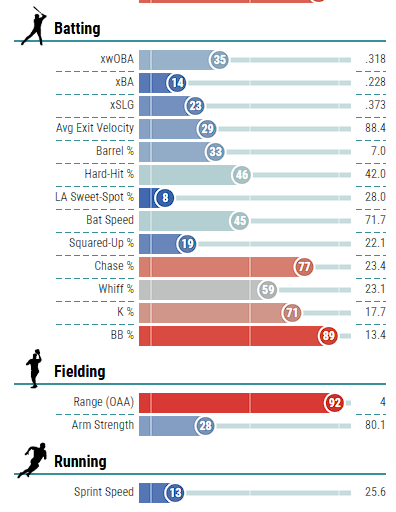

Let me explain. If you look at Santana’s Baseball Savant percentile rankings, you won’t come away impressed:

Yes, we get it, the man has an elite sense of the strike zone, and he’s still great at defense — no big surprise — but it’s a bit of a bummer if we look only at the bar graphs above Chase%; there’s not a ton of loud contact, not a ton of squared-up contact, and he’s rarely hitting the ball on the sweet spot. That’s a lot of blue for a guy running a 123 wRC+ and getting an article written about his late-career resurgence.

To understand what’s going on here, you have to look a little closer. Santana is a switch-hitter, but in recent years, he was doing most of his damage while batting right-handed. From 2020 to 2024, Santana posted a 124 wRC+ against left-handed pitchers and an 89 wRC+ against right-handers. This year, on the other hand, he’s teeing off when he gets to bat lefty, to the tune of a juicy 130 wRC+ and all seven of his homers. He hasn’t faced a ton of lefty opposition and thus hasn’t batted righty very often, but he’s only managed a 99 wRC+ there.

The first lesson here is one that you inevitably learn in baseball: Arbitrary-endpoint splits are volatile. What’s so special about 2020 through 2024? What’s so special about the first few months of 2025? Why should we expect a noisy game like baseball to stop being noisy when we zoom in? The only constant is change, and splits like these fly around even without changes in true talent level.

That said, let me show you a different split. These are all numbers on contact, for context, but here are two different subsets of Santana’s performance against righty pitching in 2025:

| Split | BA | SLG | wOBACON | xSLG | xwOBACON | EV | HH% | Barrel% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good | .424 | 1.061 | .628 | .809 | .491 | 94.0 | 55% | 18% |

| Bad | .091 | .182 | .106 | .089 | .061 | 79.7 | 8% | 0% |

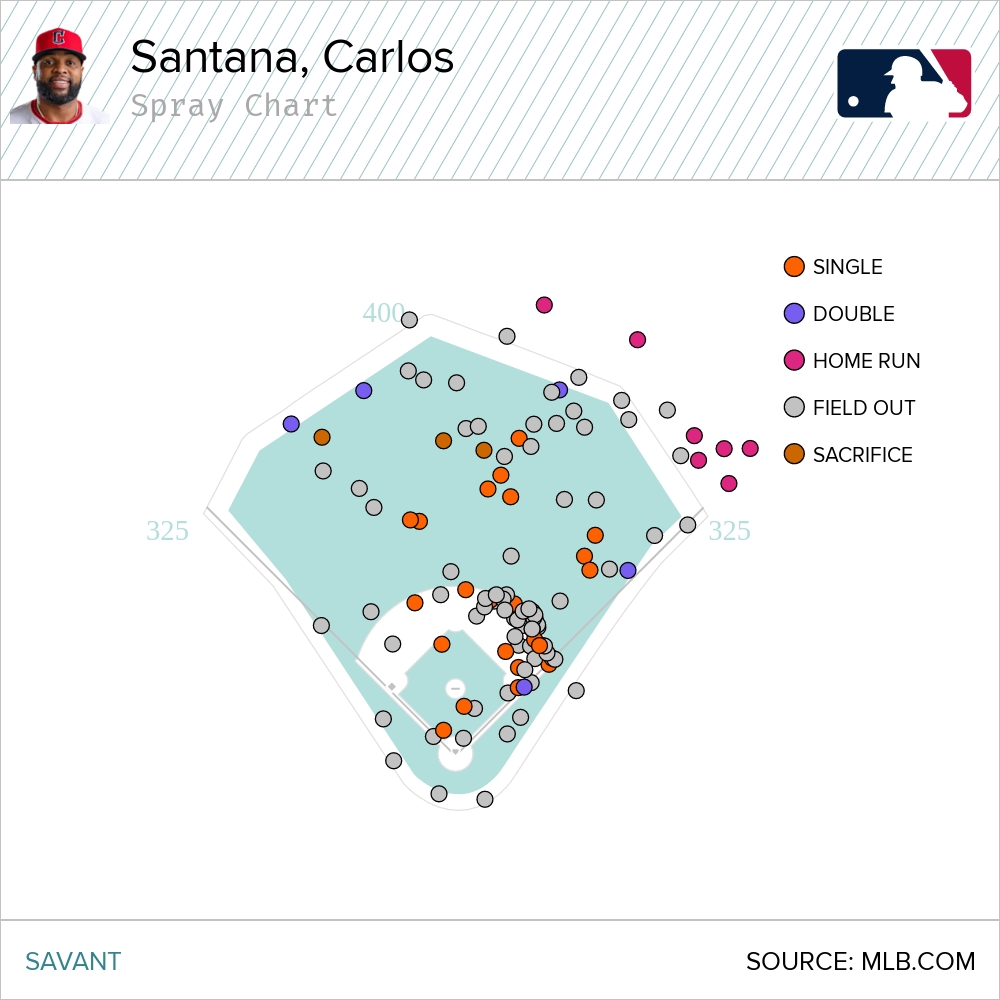

You’d fill your team with any number of clones of the first guy. The second guy might not make it in Double-A. I left it blank so you could briefly guess at what separates the two, but not for long: The table shows his performance on balls hit in the air, split by pulled aerial contact on the top row and opposite-field aerial contact on the bottom. That’s how you end up with this batted ball spray chart:

Sure, Ben, you might say. We’ve already heard about the pulled fly ball revolution. We know that hitters do better when they pull the ball than when they don’t. But I think that understates just how much Santana is selling out to pull. For example, consider the spread in exit velocities: 295 hitters have put 10 balls in the air to both sides of the outfield, and Santana’s 14.3-mph gap in average exit velocity is the 16th largest. The league-average gap is around seven miles an hour. That’s just one metric, but the same general pattern holds for everything. The point here is not that every hitter performs better to the pull side; rather, it’s that Santana performs especially better to the pull side.

That’s clear from where he hits his homers. Here’s something else that might not be immediately evident, though: In addition to doing more damage when he pulling the ball, Santana is also pulling it more frequently. Focusing only on his lefty plate appearances, he’s pulling the ball in the air more frequently this season that he has in any other year during his career. His previous high? That’d be 2024. The flip side is of course true, too: He’s never gone to the opposite field less than he is now. It’s also not a coincidence that this year and last are the two seasons in which Santana has posted his largest gaps in contact quality between pulling the ball and going the other way. More of his hits are heading to right field, and he’s becoming more fearsome when he hits the ball that way (and hitting with even less authority when he goes oppo).

You might recognize this general pattern as the Isaac Paredes approach. Hitters with good-but-not-great power – Santana fits that mold – can’t just blast homers to every remote corner of the park. They tend to do better if they can concentrate all of their best contact to the parts of the ballpark where the outfield fence is closer, and it certainly helps that almost every batter naturally hits the ball harder to the pull side.

Here’s a table from an earlier article I wrote about Paredes:

| Exit Velocity | Pull | Straightaway | Opposite |

|---|---|---|---|

| <90 | .091 | .107 | .084 |

| 90-95 | .214 | .015 | .050 |

| 95-100 | .812 | .079 | .289 |

| 100-105 | 1.043 | .598 | 1.082 |

| 105+ | 1.853 | 1.505 | 1.728 |

The relevant part of the chart here is 95-100 mph, and to a lesser extent 100-105 mph. That’s how hard Santana generally hits it when he makes good contact. He’s not ever going to be Aaron Judge or Giancarlo Stanton; as we already covered, his hard contact and barrel rates are meaningfully lower than league average. They have been for half a decade, in fact. To turn so-so contact quality into production, he has to aim for the pull side. That explains a lot about the difference between Santana’s Statcast expected numbers and his real-life production; he’s disproportionally hitting the ball to a part of the ballpark where he can get the most bang for his exit velocity buck.

Want a clear sign that this is an intentional change? Everything about Santana’s game has tilted that way. He’s swinging more often at inside pitches, and pulling them a lot when he does swing. When he hits a pitch down the middle, he’s pulling it at the second-highest rate of his long career. When he hits a fastball down the middle, the same is true. He’s swinging less frequently at outside pitches – it’s harder to pull those – but he’s also pulling them more than ever when he makes contact with them. He’s become one of the most extremely out-in-front lefty hitters in baseball, as measured by the average angle of his bat when he makes contact with the ball – eight degrees to pull, a top-15 mark among all lefty hitters in the majors.

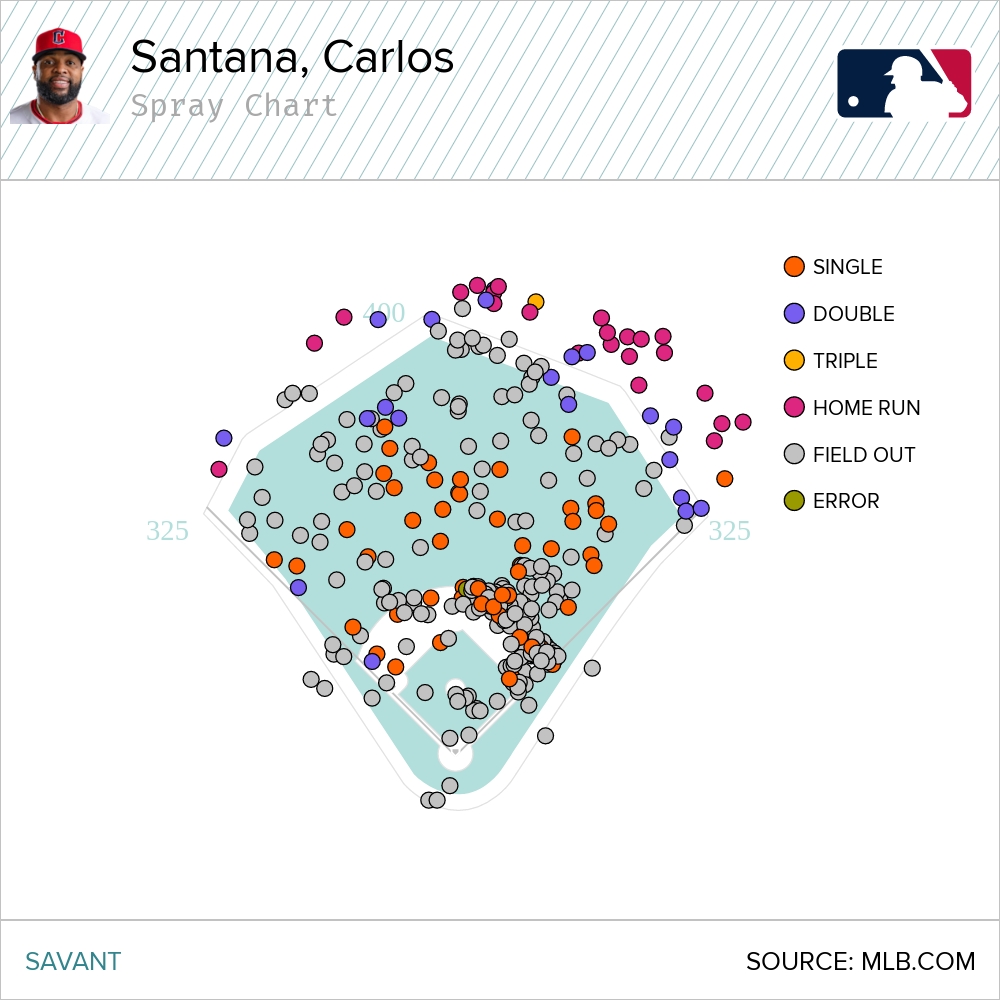

I’m particularly interested in Santana’s new approach because of his existing skill. Santana is one of the great strike zone knowers of the 21st Century. He’s walked more than 1,000 times in the major leagues, in a ridiculous 14.5% of his career plate appearances (he only strikes out 16.5% of the time). He combines solid contact skills with a preternatural ability to identify pitches quickly; if Mr. Santana thinks it’s not a strike, the odds are that it isn’t a strike. Historically, though, when he identified a pitch to swing at, he worked back up the middle — hitting it to center or maybe right-center if he was particularly on the ball. Here’s where he hit the ball as a lefty in 2019, his last great season of left-handed production before his recent resurgence:

Now, the game’s a little different: Santana appears to be turning his pitch identification skills to finding balls to pull. He’s sacrificing elsewhere to do so: When he hits the ball anywhere other than the pull side this year, it’s with the least authority he ever has. If he weren’t so good at pitch identification, I don’t think this skill would work. His teammate Jhonkensy Noel, just to give you an example, is hammering his pulled contact this year, far in excess of how hard he hits it to the opposite field, and pulling more balls than he sends the other way. He’s also striking out a third of the time and never walking, leading to a 12 wRC+.

I’m not sure how long Santana can keep this up. It feels like a ploy, a “one stupid trick pitchers can’t stand” that will be revealed as a gimmick after opponents spend enough effort learning to counter his tactic. In the long run, it’s hard to make this work. But who cares? As John Maynard Keynes said, in the long run we’re all dead. Four years ago, it looked like Santana might be on his way out of baseball. In 2025, he’s batting cleanup for a playoff contender and crushing righties as well as he ever has in his long, excellent career. Sign me up for that kind of one stupid trick every day of the week.

Ben is a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @benclemens.

No Five Things – lame

Carlos Santana article – nevermind 🙂