Catchers Can’t Catch a Break Anymore

A couple of weeks ago, I saw Jonah Heim take a called strike that he felt should have been a ball. As a catcher, Heim knew better than to argue. Instead, he performed the delicate dance of the catcher who wants to make a point without showing up the umpire. I’m not sure if the clip below is the exact pitch I saw, but it’s certainly representative of the conundrum a catcher faces when he doesn’t like the strike zone.

You can see Heim duck his head and furtively say something to home plate umpire Doug Eddings. I like to imagine that whatever he says begins with, “I beg your pardon, good sir.” He doesn’t make a show of his displeasure. He asks something, Eddings nods his head yes, and everyone moves on with their lives. Still, Heim thinks he’s seen ball two, and it’s hard to blame him. Even the person operating the score bug got fooled.

For some reason, that little moment has been rattling around in my head. I tend to think too much about the relationship between umpires and catchers. It doesn’t seem possible that they could spend every night doing what they do in the proximity that they do it in without developing a bond.

A few years ago, Holly M. Wendt wrote a prose poem called “The Steadying Hand.” It’s about when the umpire rests their hand, or almost rests their hand, on the catcher’s back in the moment just before the pitch approaches the plate. It’s beautiful, and I return to it often.

In umpire school, they teach the tight-clenched fist, the quick punch: strike, out. The steadying hand is itself feathers, barest brush to say here I am and there you are because this red half-moon of earth is only ours and we are here for nine revolutions of baseball’s sun.

Every once in a while a camera at field level allows you to see the steadying hand in action.

I don’t know whether I’ve actually heard anyone say this, but I’ve always assumed that umpires tend to give catchers the benefit of the doubt on borderline calls. After all, why does Heim have to be so careful when he protests a bad call? Because he’s afraid that if he angers the umpire, he’ll lose calls for his pitcher. Obviously, he believes that there’s a relationship there, and that it affects the calls the umpire makes.

On the other hand, maybe it’s just that they’re going to be spending the whole game back there with the umpire, and they don’t want to spend the next two hours in a fight. Managers don’t seem to worry that upsetting the umpires will cost them calls. We’ve all witnessed Aaron Boone, convinced that the calls aren’t going his way, riding an umpire mercilessly from the dugout until he gets tossed, then running out to make his point up close. I can’t imagine he’d be doing that if he thought it would hurt his team in the long run.

Previous research has told us that many factors can affect the strike zone, including the count and the game situation. In as strong an argument for an automated ball/strike system as you’ll ever find, even the race of the players and umpires has been found to affect the zone. But I couldn’t find any research specifically about catchers, aside from a cursory look from Jeff Sullivan 10 years ago.

So I pulled data on every ball and called strike in the shadow zone during the pitch-tracking era, and broke the batters down into catchers and non-catchers. Specifically, if you’re playing catcher during your plate appearance, then you count as a catcher. This isn’t a perfect system, as it excludes catchers who are moonlighting at first base or DH, which could dilute any effect we find. But that also means that it focuses solely on the catchers who are keeping the umpire company on any given day.

As we’re talking about just under 2.3 million pitches for catchers and 22 million pitches overall, the sample is big enough that we can draw some conclusions. I broke down the percentage of called strikes on pitches taken both inside and outside the zone, as determined by Statcast:

| Position | In Zone | Outside Zone |

|---|---|---|

| Catcher | 70.6% | 22.2% |

| Non-Catcher | 72.8% | 24.4% |

That is extraordinarily tidy. If you’re a catcher, you can indeed expect borderline calls to go your way more often. Both inside and outside the zone, the going rate of the camaraderie between an umpire and a catcher is 2.2 percentage points.

I also split the catchers into rookies and non-rookies. My thinking was that if umpires were, consciously or unconsciously, giving catchers the benefit of the doubt, the effect would be even stronger for catchers who’d been around long enough to earn some respect. The numbers bear that out, as veteran catchers see their advantage increase to 2.3 percentage points.

| Position | In Zone | Outside Zone |

|---|---|---|

| Veteran Catcher | 70.5% | 22.1% |

| Rookie Catcher | 72.3% | 22.9% |

| Non-Catcher | 72.8% | 24.4% |

Lastly, I ran the numbers while excluding two-strike and three-ball counts. Research shows that umpires are reluctant to call strike three or ball four, and since catchers are generally below-average hitters, they’re probably more likely to be behind in the count and therefore in line for favorable calls. The results were identical on pitches outside of the zone, but the difference was down to 1.9 percentage points on pitches in the zone. I’m comfortable calling it a wash.

So that’s a pretty definitive answer. Umpires have given catchers the benefit of the doubt, and we can put an exact number on its effect on the game. But I need to offer two important caveats. The first is that the effect of this bias is very small. The numbers indicate that over the entirety of the pitch-tracking era, catchers have benefited from 4,976 calls that would’ve gone the other way for non-catchers. That’s 0.046% of all pitches. It amounts to a tiny way for an umpire to show some appreciation for their workplace proximity associates.

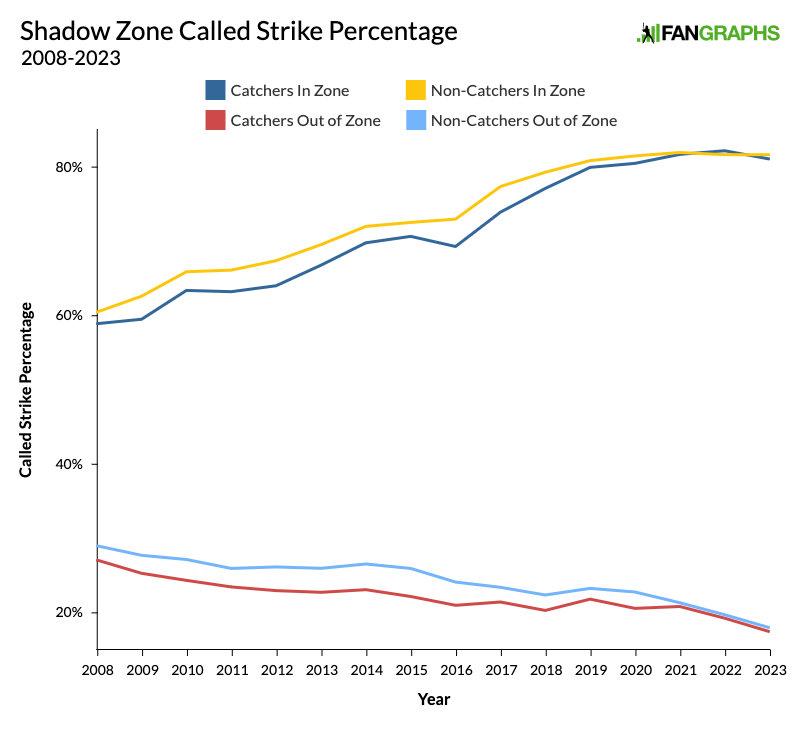

The second caveat is that this effect has disappeared. It was there. I just showed it to you in those tables. But it’s gone now. I went back and broke down the data by year, and it turns out that our original table both undersells and oversells the grace that umpires extend to catchers.

The answer to our question is a resounding yes and no. Catchers used to get those borderline calls, but the gap started narrowing in 2015 and effectively disappeared in 2021. In fact, the difference in called strike rate between catchers and non-catchers wasn’t 2.2 percentage points, as the numbers indicated earlier. From 2008 to ‘14, it was 2.6 in the zone and 2.8 outside the zone. The past few years of non-favoritism were dragging the numbers down. Over the past three years, catchers have gotten the same calls as everyone else on borderline pitches in the zone, and the difference on pitches outside the zone is down to 0.05 percentage points.

That’s not the only trend you can see in the graph above. The lines on pitches in the strike zone keep going up, and the lines on pitches outside the zone keep going down. That’s because, as I wrote back in February, umpires have been improving at calling balls and strikes throughout the pitch-tracking era, and pitch framing has evolved alongside that improvement. Here’s a graph I made at the time:

![]()

According to the Statcast strike zone, umpires have made the correct call 92.82% of the time this season. They have cut their mistakes by more than 60% since PITCHf/x data became public in 2008. MLB started using QuesTec to evaluate umpires in 2003, so the trends we see in the public data are likely a continuation of a process that started five years earlier. Regardless of how you feel about the advent of ABS, the truth is that we’ve already spent the past 20 years watching human umpires slowly turn themselves into robo-umpires.

And here’s the thing about robots, or at least robots whose sole function is to call balls and strikes: They have no souls. They are not programmed to feel the bond of kinship that grows between an umpire and a catcher. They will never ask a catcher who took a foul tip to the peanuts and Cracker Jack if he’s okay, and they will never take their sweet time brushing dirt off an already spotless plate just to give that catcher an extra minute to compose himself. They have no need for the steadying hand.

There’s just no way to get 92.82% of the calls right while also factoring in whatever feelings you might harbor about the person at the plate. As in so many areas of life, prioritizing efficiency means surrendering some of our humanity. Whatever love umpires may feel for catchers, they are no longer letting it affect their ball-strike decisions. The next time Jonah Heim gets tough luck called strike, he might as well kick up a fuss.

Davy Andrews is a Brooklyn-based musician and a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @davyandrewsdavy.bsky.social.

Great article! Is that 92.82% on all called pitches, or just the shadow zone?

Nevermind my question, your first plot implies it has to be on all pitches, since the accuracy on shadow zone tops out at ~80%.

Thanks! That’s on all called pitches. It’s 81.9% in the shadow zone, up from 80.9% in 2022.