Daniel Vogelbach, Patient Until He Isn’t

My wife spent three months working in Australia in 2019. I didn’t get to visit her thanks to a hectic work schedule, but that’s okay, because she brought back plenty of mementos from the trip. There were delicious snacks, wonderful pictures (check out the Twelve Apostles sometime if you haven’t), a t-shirt from the Australian Open, and excellent stories. None of that’s relevant for today, though. What’s relevant for today is what one of her coworkers called sharks: bitey boys.

That’s an excellent turn of phrase. It calls to mind a certain laziness combined with purity of purpose. They’re just boys hanging out, except for their one hobby: biting. Take an unsuspecting swim in their waters and you might be in for a bite. That’s just what they do.

Why bring this up on a baseball blog in 2022? I’d like to talk to you about a major league player who embodies that ethos. He’s mostly just there to hang out and live life. Sometimes, though, it’s time to bite – or in this case, swing for the fences. Meet Daniel Vogelbach, a shark lying in wait for a delicious fastball to devour.

As a rule, Vogelbach waits. Pitchers might swim through the strike zone without incident for long stretches. He swings less frequently at strikes than anyone else in the major leagues, only 47.3% of the time. Since the advent of pitch tracking data in 2008, there are only two seasons in which a hitter has notched 150 or more plate appearances and swung less frequently at pitches in the strike zone: 2008 Luis Castillo and 2010 Brett Gardner.

This is nothing new for Vogelbach. He had the lowest in-zone swing rate in the majors last year, too. For his career, he’s swung at roughly half the in-zone pitches he sees. It’s not a matter of some preternatural ability to lay off pitches on the fringes of the zone, either. No one swings less frequently at pitches over the white hot center of the plate than Vogelbach. That’s rough – those are good pitches to hit – but it also comes with benefits. He’s not one of the best hitters at spitting on bad pitches, but he’s quite good; he’s only swung at 12% of “chase” or “waste” pitches (as defined by Baseball Savant) this year.

If Vogelbach were just a run-of-the-mill patient hitter with power, I probably wouldn’t be writing this article. That’s not a particularly compelling story — large man crushes bad pitches for dingers, more at 11. But I find the particulars of Vogelbach’s patience both strange and interesting, and I hope you will as well.

Throughout his career, Vogelbach has had a fairly well-defined hot zone. When he can get his arms extended – down and in, or high and away – he’s at his best. Our heat maps demonstrate this quite effectively. Take a look at his career slugging percentage on balls in play bucketed by location:

That’s not particularly strange, especially for someone as strong as Vogelbach. Lefty sluggers have long golfed those low-and-inside pitches for home runs, and if you’re as strong as Vogelbach, muscling something high and away for extra bases is eminently achievable. No, what’s strange is where Vogelbach swings:

Up and in, he swings at a rate that, while still passive, is within striking distance of average. Aside from that, he’s looking to keep the bat on his shoulder. That’s been true for his entire tenure in the majors; a career-long swing heat map looks roughly the same.

How can we explain this disconnect? And is Vogelbach taking the wrong swing thoughts to the plate, biting at the wrong fish? I don’t think so, but it’s a more complicated question than can be solved by looking at a few heat maps. Let’s confuse the issue a little bit. He’s not swinging at his best power locations, at least based on his career numbers, but he is swinging where he makes the most contact:

There’s an interesting tradeoff here. Would you prefer to swing where you’re most likely to hit the ball, or most likely to drive it should you connect? It’s contextual, of course. If you’re David Fletcher, it might make sense to sell out for contact. After all, your power swing probably won’t result in many homers anyway.

On the other hand, if you’re Mike Trout, it probably makes sense to sell out for power, particularly early in the count; Trout’s power means that if he’s hitting the ball flush, good things will happen, and his solid grasp of the strike zone means that he’s not sunk if he gets behind in the count. In fact, for a powerful hitter like Vogelbach, count might be the primary consideration in where it makes sense to swing.

Let’s look back through Vogelbach’s swing decisions and separate them by count to see if we can find such a pattern. Here he is with zero strikes, when adding a strike to the count hurts the least:

That’s just no swings at all. Forget a bitey boy; Vogelbach is sound asleep with no strikes. His swings are concentrated over the heart of the plate, which makes sense: if he swings in these counts, it’s almost certainly at a meatball.

Next, here are his swing tendencies with one strike:

I’d roughly describe that as “try to hit something up.” Is he swinging more at inside pitches than outside pitches? Marginally, but that mostly looks like a rounding error to me. Mostly, he’s just hunting something high or that leaks over the center of the plate. None of these rates are even particularly high – he doesn’t swing a lot – but you can see him selecting a broader range of pitches to target than he does with no strikes.

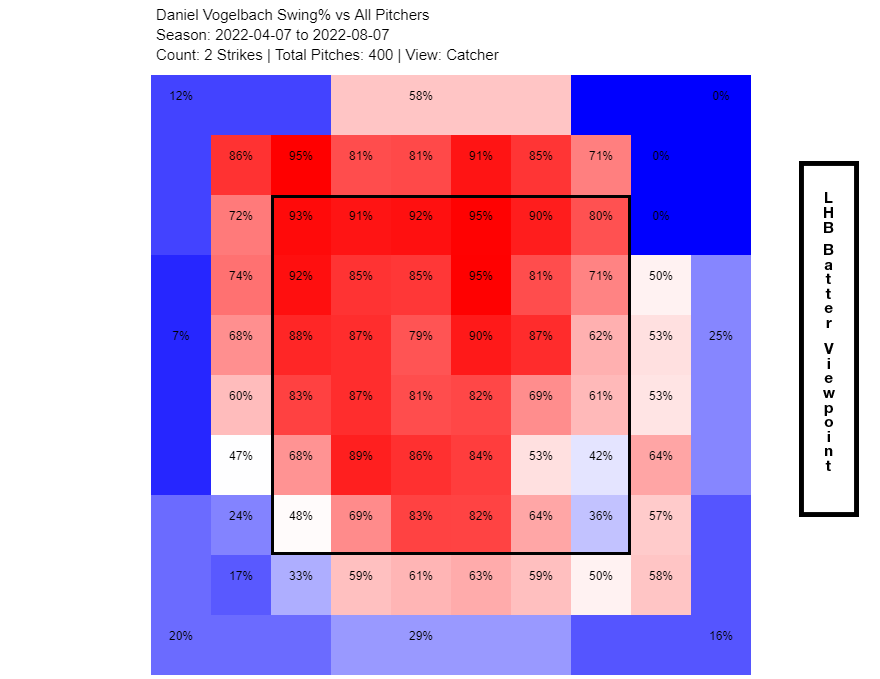

Finally, two strikes:

Now we’re cooking with gas. Vogelbach switches modes from picky-but-aggressive to voracious. Again, context comes into play: letting a strike fly by here is devastating. You can hunt your favorite pitches when passing on something in the zone means trying again in a worse count, but with two strikes, you have to take what the pitcher gives you.

Really, then, that swing map is a composite of a few things. First, Vogelbach likes to sit on high pitches early in plate appearances before expanding the zone as time goes on. That’s a smart decision in my eyes; sure, he crushes the ball down and in, but he’s not quite so productive middle or away, and it’s easier to generally look high than to look for a particular corner. Pitchers aren’t exactly eager to test lefties down and in anyway, so there are hardly any pitches for him to ambush.

As the count wears on, he’s willing to swing anywhere, but by then, pitchers are trying to stay away from his hot zones. If I told you that Vogelbach was likely to swing at something in the zone and that he’s better high and away than high and in, which of the two would you aim for? Thought so.

Pictures can deceive. One look at where Vogelbach swings would have you think that he wants the ball up and in. In reality, though, he wants the ball up, and in the counts where he’s most likely to swing, sees a few more pitches inside than outside.

As an aside, basically all of Vogelbach’s swings at low-and-away pitches come courtesy of the way he’s pitched. Lefties love to attack him there, and while he’s not helpless in that area power-wise, it’s definitely not his preferred location. But they attack him there most often with two strikes, so what is he going to do? If they were peppering him with low-and-inside pitches instead, he’d swing far more there as well. But when a pitch ends up low and inside, it’s more frequently a mistake in an earlier count, and he’s unlikely to be looking there and thus unlikely to swing.

Now, one last strange part. Here are all of Vogelbach’s career home runs that have come with either zero or one strikes in the count:

Sure, middle-middle is good, but there’s no obvious difference between up and down, yet he still prefers to swing there. With two strikes, that middle-middle tendency remains, but you can see some of his up-and-away power:

That just leaves one question: why does Vogelbach look up in the zone early in the count when he doesn’t appear to have any special affinity for high pitches? In a word, it’s fastballs. Imagine dividing the strike zone into three horizontal bands stacked on top of each other. In the top third of the zone, 75% of the pitches Vogelbach has seen so far this year are fastballs. In the middle third, 65% are fastballs. In the bottom third, only 50% are fastballs. Maybe he’s targeting an area a little bit, but the real answer here, as it so often is with hitters, is that he’s looking to hit something with no wiggle in it.

Is Vogelbach a shark? In a manner of speaking. He’s lying in wait, preparing to snack on delicious fastballs. But he’s also a defensive hitter, swinging at nearly everything in the zone when he absolutely needs to. Either approach, on its own, wouldn’t be enough to make Vogelbach a valuable major leaguer, particularly considering his limited defensive and baserunning contributions. But by combining the two approaches, he’s powerful early and tough to put away late. Just don’t expect to figure that out by looking at where he likes to swing.

Ben is a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @benclemens.

Terrific analysis!

I had no idea so much decision-making was going on beyond his tiny pivot and abbreviated swing.