Five Things I Liked (Or Didn’t Like) This Week, April 25

Welcome to another edition of Five Things I Liked (Or Didn’t Like) This Week. Normally, this column is a celebration of the extreme athleticism and talent on display across the majors. This week, though, I found myself drawn to the oddities instead. Unhittable 98-mph splinkers? Boring. Let’s talk about a pitcher who can’t strike anyone out and yet still gets results. Some of the fastest human beings on the planet stealing bases? I’d prefer some slower, larger guys getting in on the act. Brilliant, unbelievable outfield catches? I was more fascinated by a play that didn’t get made. The only thing that hasn’t changed? Mike Trout still isn’t to be trifled with. So thanks to Zach Lowe of The Ringer for his incredible idea for a sports column, and let’s get down to business.

1. In-Game Adjustments

In the 15th year of his career, Mike Trout doesn’t stand out the way he did early on. He’s no longer the fastest and strongest player every time he takes the field; he’s more “slugging corner guy” than “perennial MVP frontrunner” these days. But one thing hasn’t changed: Trout’s wonderful ability to adapt.

Landen Roupp faced the Angels last Saturday, and he leaned on his curveball. He always does, to be fair. It’s one of the best curveballs in baseball, with enormous two-plane break, and he throws it 40% of the time, more than any of his other pitches. In fact, he throws his curveball more often than any other starting pitcher. Trout had never faced Roupp before, and so he struggled to deal with the signature offering.

The first three curveballs Trout saw tied him in knots. He struck out and looked bad doing it:

Roupp doubled down on his approach to start Trout off in the fourth, and Trout took it for a strike:

Watch the appreciative nod after that pitch. “Hey, nice work, you can really spin it.” Some advice to pitchers out there: Don’t throw Trout another of the same pitch after he does that nod:

It’s not just you. I had trouble tracking that ball in the GIF. That’s because Trout annihilated it — 115 mph off the bat for a 484-foot homer. It took five curves to go from “I’ve never seen the centerpiece of this youngster’s arsenal” to “he’s never allowed louder contact.” And it got worse for Roupp, too, because Trout is capable of learning more than one thing at a time. Roupp had shown Trout a few changeups while trying to keep him off the curveball. And when Trout batted again in the sixth, he showed that he’d learned that pitch shape too:

You can fool Mike Trout – but not for long, and probably not down in the zone. Even in his latter years, that hasn’t changed.

Incidentally, Shohei Ohtani might have moved on, but the Angels are still putting up Tungsten Arm O’Doyle games. Brief summary of this one: “Trout’s bid for third homer of ballgame falls five feet short, Angels lose 3-2.” This hasn’t been Trout’s best start, or even close to it, but he’s still incredibly enjoyable to watch, even if his team can’t seem to back his efforts.

2. The Tomoyuki Sugano Experience

I can’t decide if this is a Like or a Don’t Like because I can’t figure out if I think Tomoyuki Sugano is good. He came over to Baltimore from Japan, where his decorated career had already entered the “crafty veteran” phase. He throws a kitchen sink’s worth of pitches, uses everything in every count, and leans on the “pitching is disrupting timing” aspect of his craft.

Every single Sugano start, I find myself saying, “Oh no, this isn’t working.” On Wednesday, that moment came after the second of the two titanic first-inning home runs he allowed. Last Thursday, it was the back-to-back bombs he gave up to Daniel Schneemann and Austin Hedges (really!). Combine a fastball that tops out around 94 with a zone-flooding, walk-limiting approach, and you’re going to get some explosions.

One thing you won’t get in a Sugano start? Strikeouts. He has nine strikeouts through five starts, good for an 8% strikeout rate that feels ripped from another era. His splitter, a signature during his NPB career, isn’t missing bats. Sugano’s impeccable command has been obvious right from the start – his 4.4% walk rate is no fluke – but the fact that his pitches can’t make major league batters swing and miss has been just as obvious.

The loud contact and the lack of whiffs are scary. But Sugano is doing well! He bounced back from that nightmarish first inning on Wednesday to shut the Nationals down over the subsequent six frames, ending up with a solid seven-inning, three-run day (one strikeout). The previous start, the one with the Schneemann/Hedges double dip, ended with seven innings and two runs (three K’s). Sure, all of his ERA estimators are screaming that this can’t last, but when it comes to volume and run prevention, he’s been Baltimore’s best pitcher. He’s running a 3.54 ERA and eating innings. Meanwhile, there are three different Orioles starters with an ERA above 6 this year.

How is this going to end? I really have no idea. I don’t have a good comparison for him. You think he’s Jamie Moyer? Moyer struck out 14.2% of the batters he faced in his final season – at age 49, when the league-average rate was below 20%. Sugano’s inability to miss bats stands out even compared to the finesse artists we often use as comparison points.

My cold, rational brain tells me that Sugano is going to end the season with an ERA in the high 4s. He can’t miss bats! The contact he surrenders is so loud! But, well, he’s spinning seven-inning gems even with both of those things being true. I watch all of Sugano’s starts, because every one of them feels like it should be when his spell runs out – but he just keeps doing it. It’s some of the strangest-looking baseball you’ll see all year.

3. The Great Home Robbery… Well, Almost

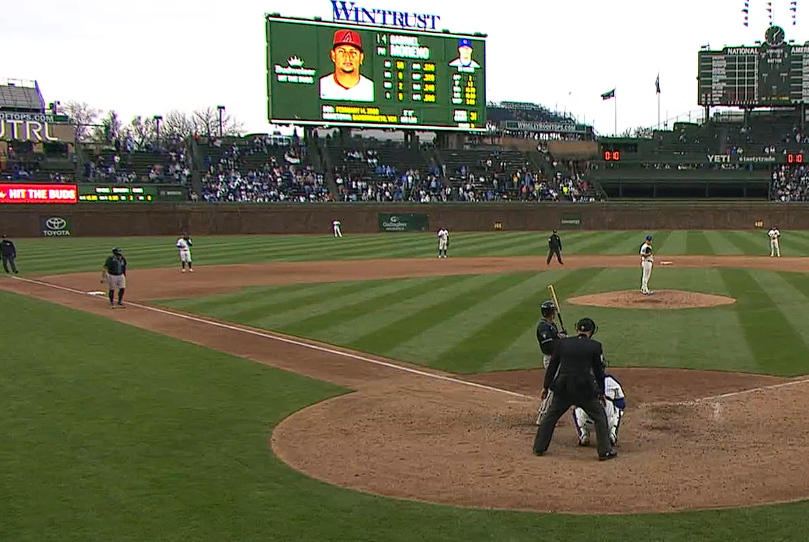

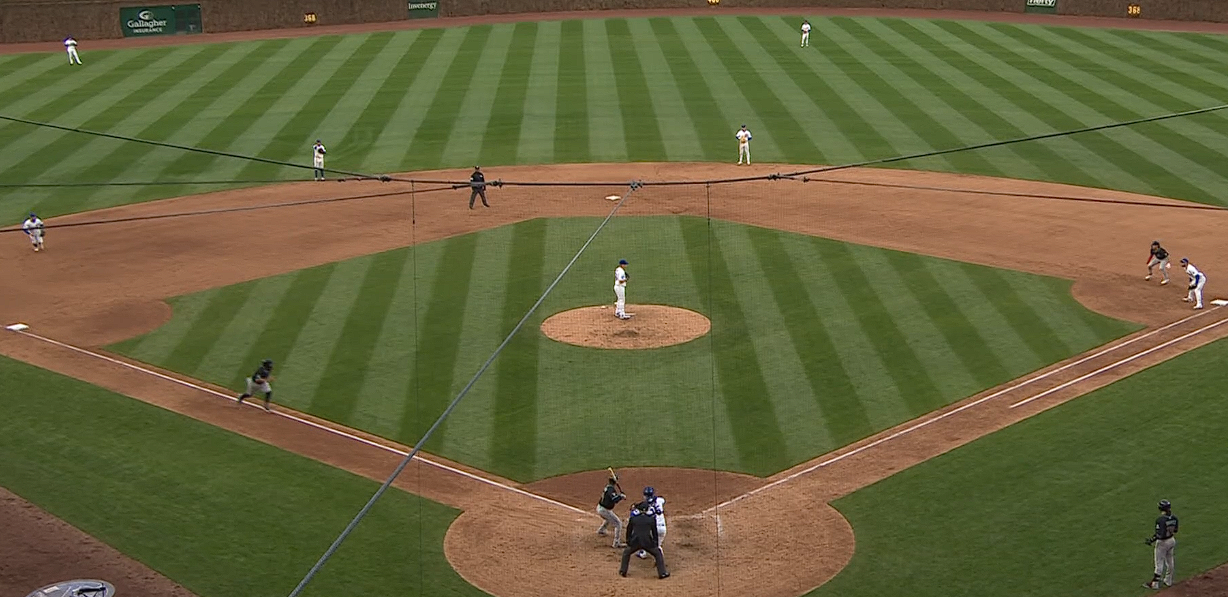

The Diamondbacks can’t stand still, at least not on the basepaths. Last year, they were one of the best baserunning teams in the majors. They’re doing it again so far this year, stealing bases and advancing aggressively. Corbin Carroll leads the way, but he’s hardly Arizona’s only player with speed to burn and a larcenous attitude. There’s Alek Thomas, Geraldo Perdomo… Josh Naylor?

Uh…

OK, an explanation is in order. Naylor really is an aggressive baserunner, and he’d been timing up Jordan Wicks for two batters. Wicks is a lefty and fairly deliberate to boot. When he gets set, he stays set. Naylor sat and watched that delivery for eight pitches: set, wait, wait, wait, throw. He watched Wicks pay absolutely no attention to him and also saw third baseman Jon Berti back up almost to the outfield grass. You can hardly blame him for feeling a little bit like Bilbo Baggins: “After all, why not? Why shouldn’t I take home?”

This one really could have worked! Look at how much time Naylor had to get up to speed before Wicks noticed:

Even saying “Wicks noticed” might be giving him too much credit. Catcher Carson Kelly all but sent up an emergency flare to get the pitcher’s attention. Kelly had been watching Naylor warily the entire time as he clocked Wicks. Kelly kept sneaking glances behind the hitter between pitches, trying to figure out where Naylor was and what he was thinking. Even then, it almost wasn’t enough. A few things went wrong that turned the heist of the century into just another out.

First, the setup. I mentioned that Berti was playing off the bag at third, giving Naylor carte blanche to walk down the line as far as he wanted. But he didn’t take enough advantage:

That’s the last frame before Naylor started into his mad dash home. If you’re going to make this ploy work, you need to be farther down the line before you take off. If Naylor had been standing three feet closer to home, what would the Cubs have done about it? Thrown over? Berti was barely in the same zip code.

There would have been time to find those extra steps surreptitiously. As Naylor astutely noticed, Wicks never looked all the way to his right. The Cubs broadcast had a camera on Wicks from the time he received Kelly’s toss after the previous pitch until Naylor took off:

I don’t believe for a second that two shuffle steps from Naylor would have drawn the Cubs’ attention. I’m not sure that an air horn could have made Wicks turn to look toward third. Naylor really was seeing something here; Wicks thoroughly ignored him. He just needed to take more advantage of that lapse.

The next issue: personnel. Naylor is fast for a human being. If you and he got into a footrace, he’d almost certainly win. But he’s incredibly slow for a baseball player – in the eighth percentile for sprint speed this year, 24.8 feet per second on average. Compared to Thomas, who was camped at first base during all the excitement, Naylor is a statue. It takes him an extra 0.2 seconds to cover 80 feet of ground, per Baseball Savant. Thomas can cover 80 feet in the time it takes Naylor to cover 75.

Now that I know what happened, this pre-play split screen keeps sticking in my head. One of these men looks like a real person, slightly winded after performing an athletic act. One looks like a Ferrari in human form. Guess which one tried to steal home:

OK, so: suboptimal jump. Suboptimal personnel. This heist could easily have worked anyway, though. Short lead, slow runner, whatever: Naylor still got an enormous head start. At the exact moment that Kelly started to rise and wave to Wicks, Naylor was nearly halfway home with a full head of steam:

From this point, the Cubs would have to be perfect to record an out. And they were. Kelly positioned himself perfectly; left foot at the front of the plate, body open, glove ready for a sweeping tag. Wicks navigated the step-off perfectly and threw a strike, putting Kelly in a perfect position to drop the tag. And still, Naylor was out by mere inches:

Maybe Naylor should be more of a mastermind than a field agent. He clearly has great awareness of what’s going on around the diamond. Now if only he could direct Carroll, Thomas, and company instead of trying to do the dirty work himself.

4. Novel Double Plays

This Kyle Higashioka foul out unfolds like an M. Night Shyamalan movie. Wait for the twist:

I had to watch this a few times before my brain could make sense of it. Higashioka hit a lazy foul pop, the kind that happens uneventfully every day. The ball hung in the air for roughly five seconds. Logan O’Hoppe took his time and played it right out of the Carlton Fisk manual: He kept his mask in his hand until he located the ball and then discarded it while taking slow, controlled steps to keep the ball dead in his sights. He was in no hurry, and he shouldn’t have been – the ball will come down at the same time no matter how you stand under it.

You’ve seen that sequence of events many times. What you’re missing is that Jake Burger was on the move. He was dancing off of first base from the moment he reached on an infield single. Ian Anderson had already thrown over trying to keep Burger close. Now, I think that Burger’s antsiness was more about a hit-and-run than a straight steal. Since the rule changes that made stealing easier were put into place before the 2023 season, Burger has attempted five steals and been caught three times. But anyway, he was going.

Burger is actually quite fast in a straight line. He has 75th percentile sprint speed. When the big man hits his stride, he chews up ground in chunks, but it takes a while to get someone that big moving that fast — the laws of physics can’t be cheated. Trains don’t accelerate or decelerate quickly either. The hit-and-run was on, and for Burger, that meant full focus on getting to second. The problem was that he got to second:

That’s not how this should work. When Higashioka popped the ball up, Burger should have slammed on the brakes immediately and retreated. Sure, maybe he can’t be watching home plate while he kicks into high gear, but the Rangers have a first base coach: “Stop stop stop!!!!” is an internationally accepted shout that will get any runner to look around. But whether Burger couldn’t hear or couldn’t translate what he was hearing into action quickly enough, he couldn’t stop his momentum until he’d touched second. I stitched together the few replays of this play and worked out that Burger touched second base roughly 2.8 seconds after Higashioka made contact. That’s just too much time spent running in the wrong direction before turning around.

You can do the math: Bobby Witt Jr., the fastest man in baseball, covers 90 feet in about 3.75 seconds. Throw in the time necessary to decelerate to a stop and turn around, and it takes a long time to take off from first, touch second, and get back to first. And that’s for Witt! Burger was out by a lot as a result:

I love the base coach, on one knee pointing out where first base is while Burger is desperately and fruitlessly hustling back. I also love what this says about the margins in baseball. A lazy infield popup, the kind every player has seen a thousand times, can still produce action. Burger wasn’t dogging it on that play. He showed great hustle and effort from start to finish. He just didn’t slam on the brakes fast enough, and if you don’t do everything right, baseball is a punishing game. I’m almost surprised that we don’t see more plays like these – and then I remember that professional athletes are spectacular at what they do.

5. Beautiful Bluffs

Watching Naylor and Burger careen around the basepaths is fun, but it’s not what you’d call graceful. This, on the other hand? This is magnificent, and I don’t mean Gunnar Henderson’s double.

Steven Kwan has won the Gold Glove in left every year of his major league career. He does it all, but his best skill is probably his inch-perfect routes. It’s incredibly hard to get a good jump and still take a direct line to the ball; the longer you think, the better your brain does at calculating the fastest way to the ball. Kwan is just better than most everyone else at that. He’s coordinated and instinctual in a way you just can’t teach.

That particular skill isn’t the good part here, but I think it’s related to the casual mastery Kwan displayed. To combine a good jump with a good route, your brain needs to make quick calculations separate from what your body is doing. If it’s not automatic, it’s not fast enough. And if all of the mechanics of seeing the ball take off, tracking it, and heading to the spot are instinctual, you might have the mental capacity to think, “Hey, I should pretend I’m catching this ball,” while making an otherwise routine play.

I’m not talking about the “here’s my glove” bluff, though that’s part of it. Plenty of outfielders try that move. But Kwan sold this with his whole body. After he realized that he wasn’t getting to that ball even on a full sprint, he didn’t panic. He just pretended he was catching a different, unrelated ball, one that happened to bring him into a good place to play a carom off the wall from Henderson’s actual missile. Watch him glide calmly like he’s playing a routine fly out:

That’s just not how outfielders look when they’re trying to track down balls hit to the extremes of their range. But Kwan was never getting to that, even with a full sprint and layout. He took his usual perfect route, it just didn’t matter. Statcast gave that ball a 5% catch probability, and I think that’s being generous given how much it was slicing toward the line. But if you were just watching Kwan, you’d think he was playing an easier ball. Compare his loping gait to this play he made last year:

Looks pretty similar, right? The difference is that in the latter play, Kwan had plenty of time to make the catch, a 75% catch probability according to the computer. That’s routine for him, and he played Henderson’s drive like it was also routine. Ramón Urías, the baserunner, bought it hook, line and sinker:

Man, you have to feel for him. He was watching the play the whole time. But there’s just no way to keep your eye on the ball from his position; all you can do is watch the fielder and pick up the third base coach if you get a chance. As best as I can tell, Urías never picked up coach Tony Mansolino, but it didn’t really matter, because I don’t think Mansolino picked up the ball in time either. I didn’t see him urging on Urías in any of the angles I watched, at the very least.

To add insult to injury, Urías didn’t last long on third. Two pitches later, he fell victim to another excellent Guardians defender:

Austin Hedges had himself a day. To bring things full circle, this came only an inning after he’d launched a home run off Sugano to give the Guardians a lead. But of course, the O’s won anyway, even without that run. They had their ace on the mound, after all. Baseball is a funny sport sometimes.

Ben is a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @benclemens.

Back-to-back weeks with Burger making an appearance, making a mistake near first base. Can he make it three??

Without you pointing out Kwan’s fake catch, I would not have noticed it in the replay. Masterful, thank you!

Shout out to the O’s broadcast for also noticing it and getting that replay of Urias rounding second

Burger has definitely qualified for the three-peat.

Hear me out: I was at the game today and the ninth inning throwaway isn’t the one that stuck with me. It’s not scoring from second on a double

“WhyNotBoth?”