I Am Declaring Victory: I Was Right About Hurston Waldrep All Along

I don’t think you can do this job for any amount of time without getting attached to particular players. Not even in the sense of having love or affection — certain ballplayers are just interesting to certain writers. For me, that manifests in just checking in with those players once or twice a season to see how they’re doing. Which reminds me, I’m overdue for my next updates on Willy Adames and Trevor Rogers.

I sometimes preface blogs about such players with the phrase, “Longtime readers might remember…”

Well, longtime readers might remember Hurston Waldrep’s splitter.

Waldrep’s splitter is a magnificent exemplar of one of my favorite pitches in the game: The ultra-low-spin splitter/split-change/forkball. He deployed it to devastating effect in the 2023 NCAA Tournament, which led to the Braves taking him 24th overall, a pick I lauded as one of the steals of the draft.

I compared Waldrep’s splitter favorably to Paul Skenes’ slider at the time, and marveled at his ability to combine a high-velo fastball and a high-spin breaking ball with this super-low-spin offspeed pitch. Pitchers with the ability to check all those boxes are few, but the following names are among them: Félix Bautista, George Kirby, Hunter Brown, Kodai Senga, Logan Gilbert, and Shohei Ohtani.

So forgive me for getting a little out over my skis on Waldrep.

Which is what seemed like had happened at this time last year. I wrote about Waldrep last June when he made his big league debut, in which he looked like a god for three innings before surrendering seven runs in the fourth. A week later, the same thing: 3 1/3 innings, two home runs, four walks, six earned runs. The Braves sent Waldrep back to Gwinnett after that, his career ERA swollen to 16.71, and forgot about him.

Truly, it appeared that they had. Atlanta entered the season with absolutely terrific rotation depth, in terms of high-end major league talent, Quad-A innings-eater types, and upper-minors prospects who could be called on at some point during the season. Sure, they had injuries to deal with, but there were plenty of able arms to hold the line temporarily. So I was not unduly concerned for Waldrep when he didn’t break camp with the team, and to be fair, he wasn’t exactly knocking the door down either.

In his first 12 appearances at Triple-A this year, dating from Opening Day to June 8, Waldrep posted a 6.35 ERA and an opponent OBP of .378. He struck out just over a batter an inning but also issued 34 unintentional walks in 51 innings. And because when it rains it pours, opponents were also 21-for-21 against him in stolen base attempts. So I’m not saying I’m outraged or anything that Waldrep had to wait until August before he saw his first major league action of the year.

Nevertheless, I had not appreciated how far down the depth chart he had fallen. This year, the Braves used 15 starting pitchers before they turned to Waldrep. That includes stars Chris Sale and Spencer Strider, 2024 breakout guys Reynaldo López and Spencer Schwellenbach, and perpetual Next Men Up Grant Holmes and Bryce Elder. They gave AJ Smith-Shawver nine starts before his elbow gave out, and cycled through a variety of openers and spot starters from the bullpen, as well as some more upper-minors depth guys like Davis Daniel.

But you can tell that things got really bleak when Atlanta started grabbing starters off waivers and the DFA scrap heap: Joey Wentz, Carlos Carrasco, Erick Fedde. This came after Waldrep was established in the rotation, but last week they fed poor Cal Quantrill to a hungry Kyle Schwarber like he was the cow in the raptor pen at the beginning of Jurassic Park, and with similar results.

I’d say that the Braves only turned to Waldrep after they were out of ideas, but 2025 Carlos Carrasco is beyond out of ideas. Not that this has had any ill effect on Waldrep, you see.

The former Florida Gator made a 5 2/3-inning, one-run relief appearance on August 2, then joined the rotation on August 9. Now, given my history of saying hyperbolic things about Waldrep, I feel obliged to point out that what comes next is absolutely literally true: Entering play Tuesday, 57 pitchers have thrown 30 or more innings in the majors since the start of August, and Waldrep has the lowest ERA of any of them.

I’m serious: 1.01 in 35 2/3 innings. Six outings, all of them at least 5 1/3 innings in length, none involving more than a single run allowed. Far from being the next-best thing to Paul Skenes, over the past month Waldrep has made Skenes look like Antonio Senzatela.

Now for just a little bit of cold water. For the first four weeks of Waldrep’s second go-around in the big leagues, he would not have noticed that he got promoted based on the level of competition. His first five opponents were the Reds, the Marlins, the Guardians, the White Sox, and the Marlins again. Those four clubs are all between 21st and 28th in the league in team wRC+. Plus it’s a small sample to begin with.

But he faced the Phillies on the most recent episode of Sunday Night Baseball and did just fine: four hits, one run, and a career-high nine strikeouts in 5 2/3 innings. And even bad teams have some good hitters, and Waldrep has held his own. This season, Schwarber, J.T. Realmuto, José Ramírez, Kyle Stowers, Bryce Harper, and Elly De La Cruz are a combined 0-for-16 with seven strikeouts against the Braves rookie. Schwarber has struck out every time he’s faced Waldrep so far this year, all on splitters.

Here’s the last one, since I feel like I owe you guys a fun video after all that preamble.

Schwarber was just three days removed from a four-homer game at this point, and Waldrep literally brought him to his knees.

The splitter is Waldrep’s most-used pitch, even to right-handed hitters, and not a lot has changed on that front. I mean, why would you? To change Waldrep’s splitter would be an affront to God the Creator. He is throwing it a tick harder, with more vertical movement, but it never had much arm-side break to begin with. This pitch has always been about a sudden down-elevator tumble, not great arm-side break.

But something had to change. Even accounting for the fact that Waldrep’s major league career, in total, has lasted eight games and 42 2/3 innings, this guy gave up an ERA last year that would’ve put him smack in the middle of the reign of Louis XIV. And this year, he’s allowed one earned run a week.

Last season, Waldrep basically threw three pitches: Most commonly a four-seamer, followed by the splitter and a slider. (He also threw five curveballs over two starts, which isn’t really worth caring about.)

During the Bad Times, Waldrep mostly followed the standard platoon approach, throwing splitters to opposite-handed hitters and breaking balls to same-handed opponents. This essentially made him two different two-pitch pitchers, one for each side of the plate.

Here’s the problem, or at least a problem. Remember how I said Waldrep’s splitter doesn’t have much horizontal movement? Neither does his slider, and they come in at the same velocity band — about 86 to 87 mph — with similar vertical movement. This is still the case, in fact.

So far this season, according to Baseball Savant, 438 pitchers have thrown 50 sliders, as well as 50 examples of a single offspeed pitch (i.e. splitter or changeup). Out of those 438 pitchers, Waldrep has the third-smallest difference between those two pitches in horizontal movement. There’s only a 2.1-inch difference between his slider and splitter in induced vertical break, and only a 0.7-mph difference in velocity.

Gilbert, a pitcher to whom I’ve compared Waldrep before, is one of the two pitchers with less horizontal daylight between splitter and slider, but Gilbert’s splitter is more than five mph slower than his slider. They’re obviously different pitches, even before you look at things like context and spin rate.

With that information, Waldrep’s struggles last year begin to make sense; evil split-change or not, he was throwing one fastball, and two secondary pitches that ended up in basically the same place at the same time.

Two things are different with Waldrep’s repertoire this year. First, he’s throwing his curveball more. Not a lot more (only 12% of the time), but more than the slider. He’s pounding the deuce more frequently to lefties (16.0% of pitches) than righties, which on its surface flies in the face of everything we know about platoon-based pitching theory. Throwing breaking balls to opposite-handed batters is usually a bad idea.

But in the context of Waldrep’s slider and splitter, it makes sense. His curveball is a completely distinct pitch, one that allows him to drop into a different velocity band (the low 80s) that he wasn’t able to touch before, and with significant glove-side movement unmatched by anything else in his repertoire. Lefties have only made contact with it on half of their swings, and they’ve only put it in play twice. If nothing else, it’s a much-needed new look for Waldrep.

The other thing that’s changed is (takes a shot, puts a dollar in the swear jar), Waldrep has added a cutter.

It’s more than that, in fact. Waldrep has all but abandoned his four-seamer entirely, in favor of a fastball mix that’s about two-thirds cutters and one-third sinkers. (Fastballs as a whole make up a little less than 40% of Waldrep’s total output.)

I mentioned earlier that Waldrep had struggled in the upper minors while the Braves were in dire need of arms, and that as of June 8, his Triple-A ERA was 6.35. Well, he made seven starts between that date and his call-up, and over that time he allowed a 1.99 ERA, with an opponent slash line of .203/.287/.345. That’s the kind of outstanding performance that begs for a shot in the majors, even in a small sample.

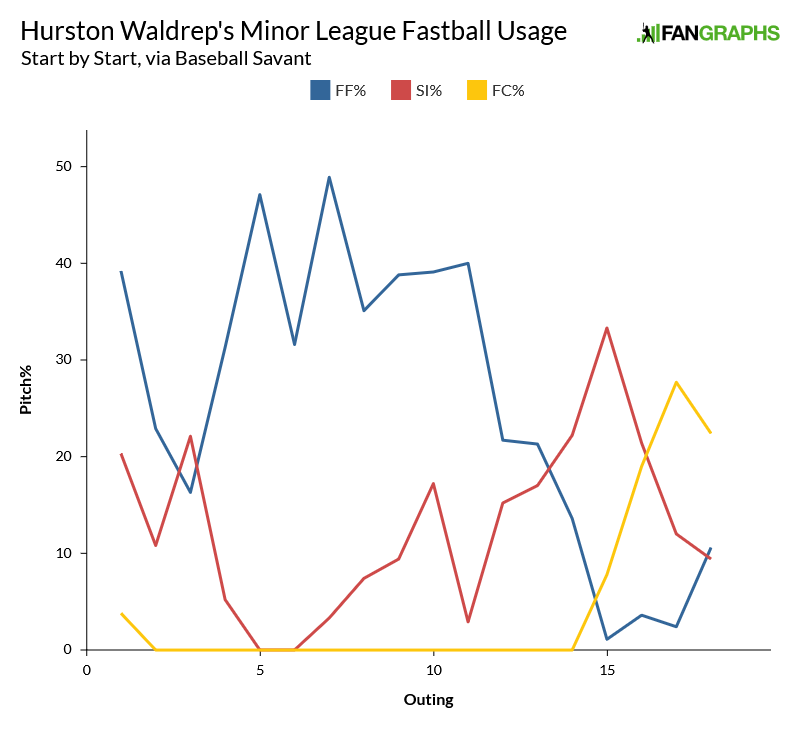

I drew the dividing line between Waldrep’s 12th and 13th minor league starts this season. With that in mind, here’s his start-by-start fastball mix in Triple-A. Let me know if anything changed around start no. 13.

I still think there’s work to be done on Waldrep’s menu of fastballs; even in a small sample, opponents have a .400 xwOBA or better against all three of the cutter, the slider, and the vestigial four-seamer (all 13 of them). But Waldrep doesn’t throw that many fastballs; out of 239 pitchers who have thrown 250 or more fastballs as starting pitchers this year, only 16 (including Gilbert) have thrown fewer all-type fastballs than Waldrep.

But he’s not getting absolutely slaughtered on hard stuff like he was last year; none of those three fastballs are more than a run either side of average, according to Baseball Savant.

More promising: Here’s how opponents are faring against Waldrep’s secondary pitches: .088 wOBA and 45.7% whiff rate against the splitter, .126 wOBA and 31.3% whiff rate on the curveball, and .223 wOBA and 19.4% whiff rate on the slider, which was an absolute liability last year. That’ll play.

In other words, Hurston Waldrep is good now. Just like I said he’d be all along. I have predicted the future. You’re welcome.

Michael is a writer at FanGraphs. Previously, he was a staff writer at The Ringer and D1Baseball, and his work has appeared at Grantland, Baseball Prospectus, The Atlantic, ESPN.com, and various ill-remembered Phillies blogs. Follow him on Twitter, if you must, @MichaelBaumann.

I love a good 12-6 rainbow curve, but to me, the most aesthetically pleasing pitch in baseball is a splitter that starts thigh-high and ends at a dude’s ankles. There’s something magical about the proverbial “falling off a table” that I love.

I don’t know if you’re old enough to remember Mike Scott, but if not you ought check out some video circa 1986 when Scott was the most dominating pitcher in baseball (8+ WAR, 300+ Ks) thanks to the most devastating splitter most had ever seen. He learned it from famed pitching coach and apostle of the splitter Roger Craig.

’86 was right on the early periphery of me following baseball, so I have some real hazy memories of Scott in his prime. Should try to dig up some video.