I’ll Have an Isaac Collins, Please, Bartender

I used to have a bit that one of the joys of the postseason was watching the wider baseball-watching public discover a previously unknown Rays pitcher when he mowed down the Astros in the first nationally televised game of his career.

It’s a little harder to pull that off as a position player: Go from complete unknown to key regular on a playoff team. In fact, a lot of the most important position players in this pennant race — Shohei Ohtani, Kyle Schwarber, Manny Machado — were names before they even joined their current teams.

On the other hand, you’d be forgiven for not knowing Isaac Collins.

The Brewers offense, as I’ve written repeatedly over the years, is usually not the fun part of the machine. And even if it were, there are some big names, or at least bigger names than Collins’. If you want to go down the line name by name, Collins has the least impressive biography of any regular in Milwaukee’s ideal lineup (so including the currently injured Rhys Hoskins and Jackson Chourio).

Christian Yelich is on the downslope, but he’s a former MVP. Sal Frelick, Brice Turang, and Andrew Vaughn were all high draft picks and top prospects. Hoskins and William Contreras were splashy acquisitions with playoff experience. Joey Ortiz was the centerpiece of the Corbin Burnes trade… OK, I’ll grant you that the third base platoon isn’t that exciting either. Still, Collins blends in, even in a lineup without the star power certain richer coastal teams can boast.

Technically, Collins was a Rule 5 pick, but his origins with the Brewers are so much less glamorous than that. He was drafted by the Rockies in the ninth round out of Creighton in 2019, and after four seasons in the minors, the Brewers snatched him up from Colorado in the minor league phase of the Rule 5 draft.

Collins can switch-hit, which is cool, but he’s 5-foot-8, 188 pounds, with no remarkable physical gifts. He’s an average runner, and while he’s got good bat speed, that hasn’t exactly contributed to big power. Collins’ EV90 this year, 103.9 mph, is 118th out of 285 players with 200 or more plate appearances this season. His career-high ISO at any minor league level is .201, and his career high in home runs is 14.

In this May’s Brewers Top Prospects list, Collins came in 38th, which is actually quite a compliment. He entered the majors unlikely to play a premium position and without a single tool grade over 50, even in future projection. Not that you’d project anything more from a player who was about to turn 28 (which he did two weeks ago; many happy returns, Isaac). For a player like that to end up on a prospect list at all is unusual.

Three months later, here he is, hitting in the middle of Milwaukee’s lineup, in what I’d describe as a practical four-way tie with Frelick, Contreras, and Freddy Peralta for the title of the team’s most valuable player by WAR.

Collins has been terrific defensively in left field, which helps. He’s tied for the league lead in FRV for left fielders with Steven Kwan, who’s played more than 350 more innings at the position. Of course, to say that Collins is a great left field defender is damning with faint praise. The thing that’s actually kept this undersized, unfancied, too-old-rookie, limited-power corner outfielder in the lineup is a concept worth throwing a dollar in the Moneyball swear jar for.

Here’s a full list of National League hitters with 200 plate appearances and an OBP higher than Collins’, as of August 5: Will Smith, Ketel Marte, Kyle Tucker.

Moneyball isn’t just a worthwhile reference here because Jonah Hill says the line; it has to do with why I think Collins is interesting. The simplest, most facile-bordering-on-misleading takeaway from the book (and later the movie) is that baseball teams can win more if they load up on guys who walk.

The more accurate one-sentence summary is that smart teams can gain an advantage by identifying classes of player whom contemporary analysis underrates. The characteristics of this class change from one year to the next; in 2002, it was guys who walk. A few years later, it was good defenders, then hitters who strike out a lot but hit for power, then pitchers who throw sinkers, then pitchers who throw four-seamers, and on and on and on.

I would say most stats people retain a soft spot for hitters who walk a lot, if only because we all remember what was fashionable in our formative years, but fashions change. Guys who walk are no longer undervalued for several reasons. First, every major league GM has read Moneyball, too. Second, now that everyone knows how valuable walks are, pitchers tend to avoid them if possible. That means hitters have to earn their walks, leading to point no. 3: Guys who walk a lot tend to also be good at other stuff, and are therefore expensive to acquire.

Here’s an example. All the stats that you see on FanGraphs’ various leaderboards that start with a lowercase w (or most of them, at any rate) are based on a linear weights system. Every contribution that a hitter makes — walks, singles, doubles, and so on — is worth a certain number of runs. How many runs changes by year; you can find the whole table here.

Everything in that genre — wRC+, wRAA, wOBA — comes from totaling up those runs and comparing them to league average, adjusting for park effects, and what have you. Here are the hitters who have drawn the most unintentional walks this year, and have therefore generated the most value by taking their base. (All stats from here on out are current through August 4.)

| Name | Team | PA | BB | wBB |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Juan Soto | NYM | 488 | 85 | 51.2 |

| Rafael Devers | BOS/SFG | 515 | 80 | 49.8 |

| Marcell Ozuna | ATL | 425 | 73 | 49.1 |

| Kyle Schwarber | PHI | 498 | 74 | 47.7 |

| Kyle Tucker | CHC | 488 | 75 | 47.1 |

| Geraldo Perdomo | ARI | 494 | 65 | 45.0 |

| Matt Olson | ATL | 495 | 66 | 44.3 |

| Vladimir Guerrero Jr. | TOR | 496 | 68 | 42.2 |

| James Wood | WSN | 482 | 66 | 40.1 |

| Shohei Ohtani | LAD | 512 | 71 | 40.1 |

And hot damn, would you look at that, it’s just a list of either nine or 10 really good hitters, depending on how you feel about Geraldo Perdomo. This list of 10 players includes the three biggest contracts in baseball history in total value, plus Devers (who’s in the top 20) and Tucker (who will be this time next year).

Out of the Brewers’ price range.

Let’s see another table. Using the formula for wOBA, I calculated a version that removes walks from both the numerator and denominator, then compared it to the original formula to see who’s generating the highest proportion of their offensive value through walks. Here are the 10 hitters (min. 200 PA) who benefit most from being able to walk.

| Name | Team | PA | wRC | wOBA | wOBA-uBB | Delta | Walk Value/wOBA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marcell Ozuna | ATL | 425 | 58 | .338 | .267 | .072 | 21.1% |

| Max Muncy | LAD | 319 | 49 | .359 | .296 | .064 | 17.7% |

| Juan Soto | NYM | 488 | 79 | .368 | .308 | .060 | 16.2% |

| Pavin Smith | ARI | 264 | 40 | .357 | .298 | .058 | 16.4% |

| Joey Bart | PIT | 246 | 27 | .303 | .245 | .058 | 19.2% |

| Bo Naylor | CLE | 289 | 29 | .292 | .235 | .057 | 19.6% |

| José Caballero | TBR/NYY | 278 | 27 | .289 | .234 | .055 | 19.1% |

| LaMonte Wade Jr. | SFG/LAA | 242 | 14 | .242 | .187 | .055 | 22.7% |

| Rafael Devers | BOS/SFG | 515 | 80 | .361 | .306 | .055 | 15.2% |

| Matt Chapman | SFG | 376 | 53 | .345 | .290 | .055 | 15.8% |

A lot of the usual suspects, but a couple of these guys stink. All they have going for them are walks. Take Wade, for instance. In 2023, he hit .256/.373/.417 with 17 home runs. He was a well above-average hitter, thanks largely to the fact that he never swung outside the strike zone. This year, his exit velo numbers fell, pitchers started pitching him in the zone more, his batting average dropped almost 100 points, and the whole castle came a-tumbling down.

Wade went from a 120 wRC+ to getting cut by the Angels in less than a year. If you can’t do damage on pitches within the zone, there’s no incentive for a pitcher to let you walk.

You’ll notice Collins hasn’t been on either of these tables so far. He would’ve been 25th out of 285 on the second table, placing him within the top 10 percent of the league in walkless wOBA-regular wOBA.

Which is in keeping with his minor league performance. Collins put up some ludicrous walk numbers in the minors; he walked 20.0% of the time during his first year in the Brewers system, in 96 games across Double-A and Triple-A.

There’s no guarantee that walk rate would transfer; a lot of guys who put up numbers like that in the high minors either get the bat knocked out of their hands or don’t take the bat off their shoulders in the majors. (This is why I was so interested in Chase Meidroth when he got called up earlier this year.)

In that 200 PA-and-up group, Collins is 26th with a walk rate of 12.9%, which is great news in and of itself, because while it’s possible to be a bad hitter with a walk rate of (rounding things up) 13%, it’s highly unusual. The top 21 players on that leaderboard in walk rate all have a wRC+ of 117 or better.

The question is whether Collins has the juice to stay up there. Here’s a leaderboard on which he shows up near the top: the 10 lowest chase rates in baseball.

| Name | Team | Chase% | HardHit% | BB% | wRC+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Juan Soto | NYM | 15.2% | 55.3% | 17.4% | 142 |

| Gleyber Torres | DET | 16.7% | 40.4% | 12.8% | 126 |

| Liam Hicks | MIA | 17.2% | 27.5% | 11.2% | 107 |

| Isaac Collins | MIL | 17.8% | 38.2% | 12.9% | 131 |

| Kyle Tucker | CHC | 17.9% | 42.3% | 15.4% | 144 |

| Trent Grisham | NYY | 17.9% | 44.0% | 13.7% | 133 |

| TJ Friedl | CIN | 18.1% | 29.7% | 11.5% | 117 |

| Josh Rojas | CHW | 18.7% | 34.8% | 8.9% | 42 |

| Tommy Pham | PIT | 18.8% | 45.6% | 9.7% | 100 |

| LaMonte Wade Jr. | SFG/LAA | 18.8% | 31.8% | 11.2% | 5 |

These guys won’t get themselves out by chasing, but hitters who can’t help themselves by hitting the ball hard can get swamped by pitches in the zone. (Except TJ Friedl, apparently, who continues to be the weirdest hitter in the league.)

I don’t think Collins is a poor man’s Soto or anything. Well, he might be, but, like, a really poor man’s Soto. But Collins is doing enough to survive in other areas of hitting. He’s putting up average whiff numbers, and while his .281 batting average is buoyed by a .356 BABIP, he’s still hitting .281. Collins is also getting the most out of his hard contact by hitting the ball in the air and to pull; his in-air pull rate is 21.5%, compared to the league average of 16.7%.

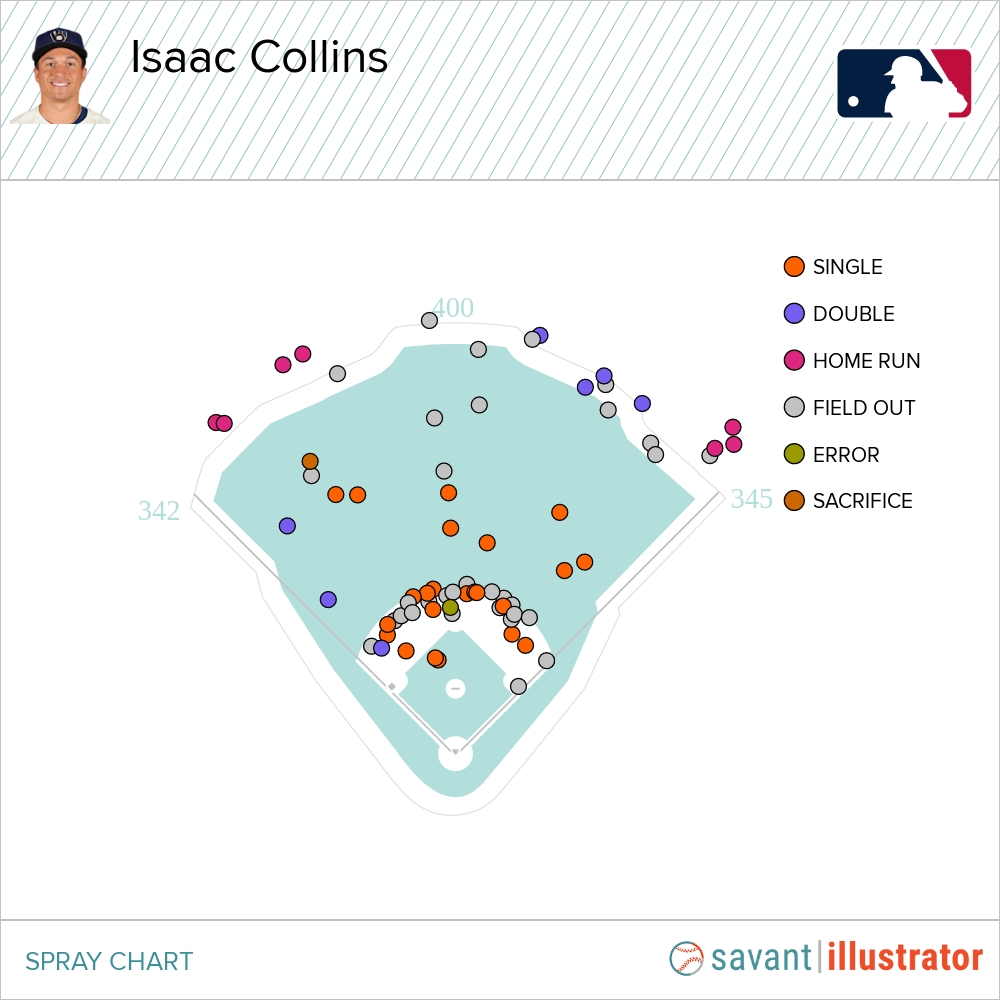

Five of Collins’ seven home runs this season have been down the lines, and here’s a spray chart of his hard-hit batted balls this year. (Remember, he’s a switch-hitter.) Not a lot to dead center.

Collins is elite in one aspect of hitting: strike zone judgment. I don’t know if he’s even good at any other part of the offensive game. But he’s been average enough everywhere else to make his one standout skill, well, stand out. As a result, this rookie nobody heard of before this season has been one of the most valuable players on the team with the best record in baseball.

Michael is a writer at FanGraphs. Previously, he was a staff writer at The Ringer and D1Baseball, and his work has appeared at Grantland, Baseball Prospectus, The Atlantic, ESPN.com, and various ill-remembered Phillies blogs. Follow him on Twitter, if you must, @MichaelBaumann.

Thanks for the article. At this level of play he’s a modern day Roy White.

No idea if it’s sustainable long term. But at minimum he’s a good 4th outfielder between the ability to take a walk, play defense and switch hit

He’s almost the platonic ideal of a fourth outfielder. In addition to everything you said, he runs well enough to pinch run late in the game, he’s got enough power that you can’t ignore it, and he could probably play center in a pinch, although you wouldn’t want that for a long time. He could even pinch hit for a light hitting catcher or infielder.

He kind of does a little bit of everything well enough without having any tool that says “you have to get this guy in the lineup,” assuming his BABIP reverts a little and he doesn’t keep running a .385 OBP.