Isaac Paredes Is Out in Front

Everyone should have one weird player they love. If I were commissioner of baseball, this would be part of my pitch to fans. There are a million different ways to succeed in this sport we all love, and if you only like the guys who swing hard, throw fast, and run well, you’d miss the splashes of color that dot the sport. Tyler Rogers pitches upside down. Jose Altuve is small but mighty. Luis Arraez swings slowly on purpose. Then you’ve got my personal favorite, Isaac Paredes, who is among the league leaders in WAR thanks to his one weird trick.

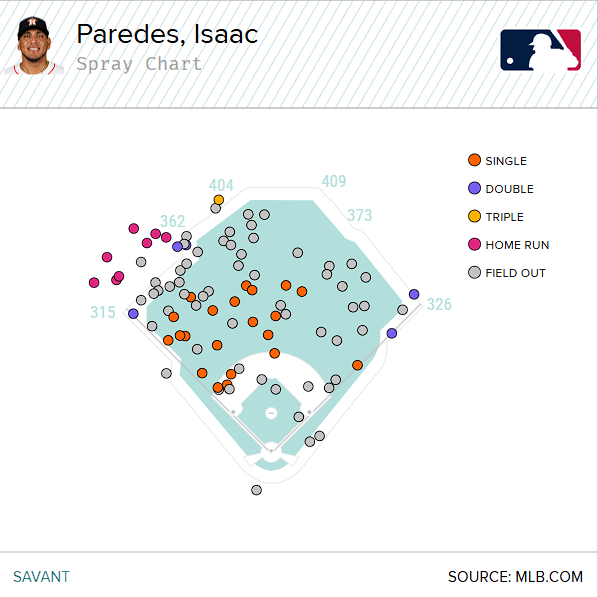

That weird trick is incredibly valuable: pulling the ball in the air. Take a look at the distribution of his aerial contact this year:

Paredes isn’t going to wow you with barrels. His hard-hit rate is among the league’s lowest. Many of those home runs look farcical. This one would be out of only five parks:

I know, I know, this isn’t news. I’ve been writing about Paredes’ pull-only power for years, marveling at his ability to rack up star-level production with journeyman-level raw tools. Since the start of the 2022 season, when he first became an everyday regular, he’s been worth about as much WAR as Bryce Harper (11.9 to Harper’s 12.4) in about as many plate appearances (1,798 to Harper’s 1,818). Some of that is defense, but even if you want to compare him on the offensive end, he’s matched Carlos Correa, Anthony Santander, and Corbin Carroll at the plate.

Paredes hasn’t received the acclaim that you’d expect from those statistics, and the sheer strangeness of his game explains why. He played in a perfect park for his lift-and-pull antics in Tampa Bay. When he spent half a season with the Cubs last year and played home games at Wrigley Field, he looked ordinary. Put him in Houston, with its iconic short porch in left field, and he’s great again. Is he just product of weird stadiums?

Obviously, that has a lot to do with it. But Paredes isn’t the only player who gets to play in these stadiums. Plenty of guys with superior bat speed play in Houston and Tampa Bay, and yet Paredes led the Rays in homers during his time there and tops the Astros in dingers this year. And as I’ve documented over the years, it’s not just that Paredes hits a ton of fly balls. He also pulls his best contact at a rate that far outstrips the rest of the league, and with elite pitch recognition and bat-to-ball skills, he rarely goes a plate appearance without either getting ahead in the count or trying to loop something over the left field wall.

None of this is new this year; Paredes is off to a good start, but he’s played more or less like this for years now. I’m writing this because the league just released some new data that shed a bit more light on how Paredes does it, at least physically, and there’s just something wonderful about understanding the mechanics that power such a simple strategy.

As David Adler noted in his examination of the new swing path data, Paredes’ bat is angled more to the pull side, at point of contact, than any other player in baseball. It’s worth reading that whole article, which is chock full of information on swing path outliers, but the Paredes section just confirms what you’d already guess. No one in baseball has his bat more tilted to pull than Paredes does when he makes contact, because no one else in baseball pulls the ball more frequently when he takes his best swing.

That’s a direct explanation of how it works, but the indirect parts of this interest me, too. How do you achieve that pull-side tilt? By hitting the ball when your bat is already curling around back toward you – out in front of the plate, in other words. If you imagine a hitter’s swing, there’s a point where the bat is exactly parallel to the front of home plate. Hit the ball before that parallel point, and some of the energy the bat imparts to the ball will point to the opposite field – right field for right-handed hitters like Paredes. Hit the ball after the parallel point, and you’re directing the ball to the pull side. Easy!

With this new data release, Baseball Savant has metrics for where hitters make contact with the ball. Which hitter is farthest in front when he makes contact with the ball? Awkwardly for this article, it’s Hunter Goodman. Paredes isn’t even in the top 10. But that just raises an interesting question: How can those two things be different?

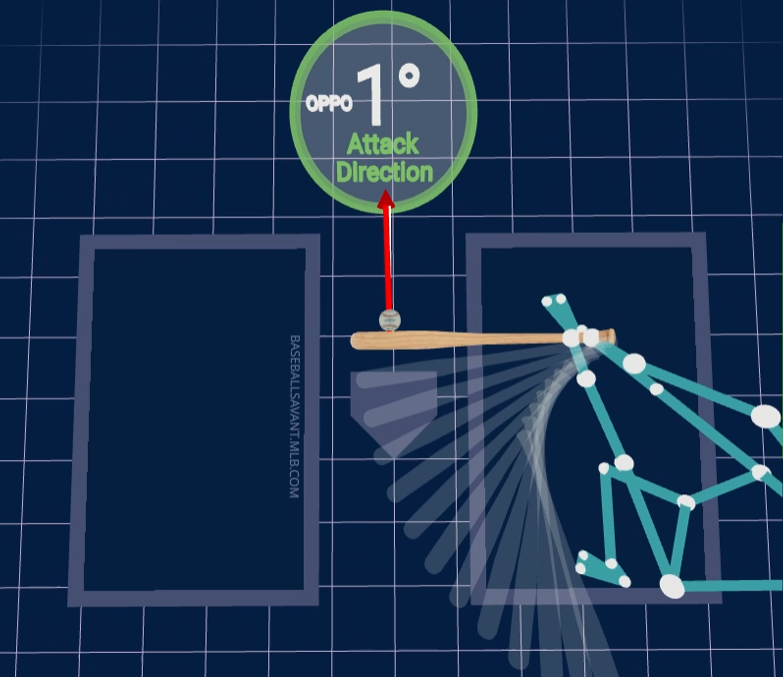

The best exhibit for why hitting the ball out front isn’t the same as hitting it to the pull side is Elly De La Cruz, specifically as a lefty. De La Cruz is one of the most extreme hitters when it comes to his contact point; he makes contact with the ball 37.8 inches in front of his center of mass. Paredes checks in at a relatively modest 34.7 inches. But De La Cruz’s bat is actually angled to the opposite field when he makes contact. How can that be? This graphic explains it fairly well. Here’s De La Cruz at the point of contact:

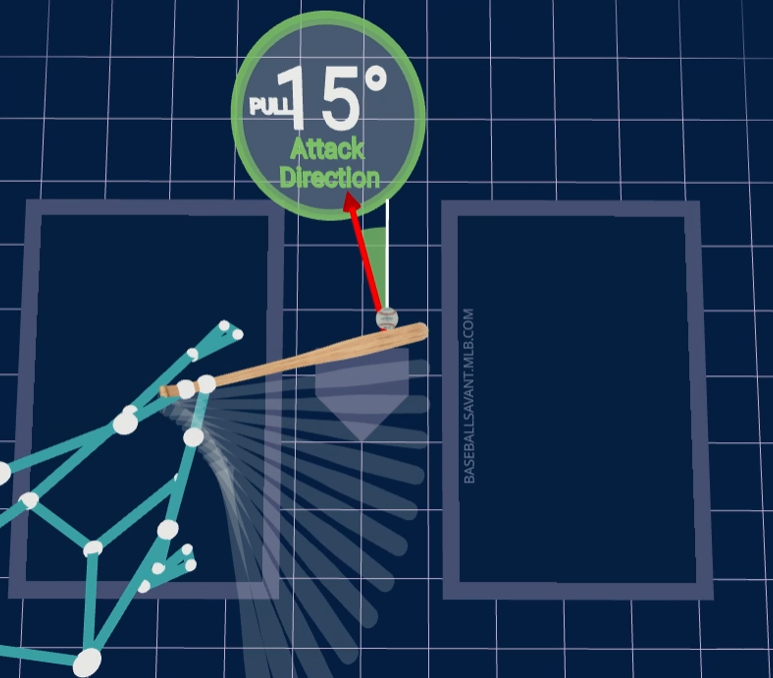

Contrast that with Paredes, who achieves far more pull-side tilt despite not getting the bat as far forward:

Another way to think about it: When De La Cruz makes contact with the ball, he’s right in the middle of his swing. He hasn’t yet broken his wrists to pull the bat up and over his shoulder. He has a long-ish stride, though, and he’s of course a huge guy with long arms, so getting that whole swing off just takes more space. Paredes, on the other hand, is deep into his swing when he makes contact. His wrists are already starting to rotate the bat up into his backswing. Sure, he’s hitting the ball closer to his torso, but it’s farther into his swing, which is what really counts.

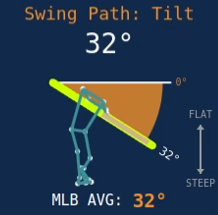

Here’s another way of thinking about that: De La Cruz and Paredes have very similar swing tilt. This graphic does a great job of explaining what that means:

The same swing tilt doesn’t mean the same launch angle, though. That’s because Paredes hits the ball later in his swing, after the bat has done all its descending and is meaningfully far into the part where it comes back up. His attack angle – the angle between the bat path and the ground at the point of contact – is steeper than De La Cruz’s not because of the shape of their swings but because of where in the swing they each make contact. The same swing plane can produce different angles of contact with the ball depending on where in the swing the hitter makes contact.

Here’s a related point: Although Paredes hits the ball closer to his center of mass than De La Cruz does, his bat travels farther before contact. It’s already through the descent and well on the way back up; meanwhile, De La Cruz is hitting his closer to the inflection point. It’s a large gap, actually; at the point of contact, De La Cruz’s swings are nearly 10 inches shorter than Paredes’s on average, and that’s despite his bat traveling faster – he has elite swing speed, after all, while Paredes is bottom tier in that category.

For me, this examination of the new data mostly proves how difficult it is to make sense of intercept points, swing tilt, and the assorted other new data we’re getting. The myriad interactions make it tricky to point to any single data point and use it to explain the world. But by adding all of this together, we can start to paint a picture of how Paredes accomplishes his pull-homer feats.

To make contact with the bat more angled to the pull side, you have to get farther into your swing before connecting. To do that, you have to start your swing earlier. When you do that, you’ll also hit the ball at a higher vertical angle thanks to the way swing tilt works. The number of moving parts is astronomical, which makes sense if you stop to think about all the body parts you use to swing a baseball bat.

Can we clone Isaacs Paredes into an army using these data and overwhelm the left field fence in Houston? Absolutely not. If anything, I think that this granular look at swing data makes it even more clear how difficult it is to do what he’s doing. He has to take a longer swing than De La Cruz – at a slower speed – to unlock his special ability to hit “easy” home runs. That means he’s making the decision to swing earlier. You’d think that would lead to strikeouts and bad swings – but nope, Paredes is among the best in the game at that.

In fact, I think that the new swing metrics mostly just validate what I’ve always thought about Paredes. His true great skill isn’t anything about his batted ball distribution or launch angle. He’s a strike zone genius. Pitchers try to locate the ball down and away against Paredes; naturally, that’s the toughest place for him to execute his swing. He spits on those pitches, and gets defensive with two strikes – no small feat considering that he has to decide whether or not to swing earlier than your average hitter. If he had an average batting eye, or even worse, had trouble with chasing too much, this plan would never work.

But oh, how it’s working this year. Pitchers are absolutely terrified of getting Crawford Boxed by him this year, so they’re treating him with deference. Nearly half the pitches he’s seen in 2025 have been either on the lower outside quadrant of the plate or out of the zone in that direction, a career high by a mile. He’s responded by just taking those pitches. He’s never swung less frequently at balls or strikes. If a pitcher hits that low-and-away corner for a strike so be it; Paredes is going to make him do it again.

Of course, Paredes also has a plan for when he’s forced to swing at those balls: Swing more often but less aggressively. He decreases his swing speed with two strikes and changes his approach to shorten up and foul pitches off. When pitchers throw him something on the outer half of the strike zone early in the count, he swings less than half the time. With two strikes, that shoots up to around 90%. He gets more aggressive on the inner half, too – but he’s already quite aggressive on the inner half, swinging at 60% of pitches early in the count.

In other words, Paredes has one of the best senses of the strike zone of anyone in the majors. If he were a giant dude, with muscles on his muscles, or perhaps a quick-twitch phenom capable of generating huge swing speed with the flick of the wrist, he might play like Aaron Judge or Kyle Tucker. But he’s not. He’s a good enough athlete to play in the majors, but he doesn’t stand out among his counterparts there. So he’s figured out a new way to beat pitchers – and thanks to Statcast’s new swing tracking data, we know more than ever before about how he does it.

Ben is a writer at FanGraphs. He can be found on Bluesky @benclemens.

Damn. This article is like a majestic home run from one of the best in the game (that is baseball writing.) Bat flip, Ben. Bat flip.