José Soriano Can Get You to Whiff, but He Won’t Strike You Out

On any given pitch, a swing-and-miss is the best possible outcome for the pitcher. The ball isn’t put in play, the count advances in favor of the pitcher, and the batter may look a little foolish in the process. It stands to reason that pitchers who possess multiple pitches that run above-average whiff rates will likely have strong strikeout rates, too. Then there’s another, much smaller group of pitchers who have multiple pitches with elite whiff rates. Those rare hurlers will surely have the best strikeout rates in baseball, right? Among all starting pitchers this season, there are just eight who possess multiple pitches that generate a whiff more than 40% of the time.

| Player | Number of Pitches With >40% Whiff% | K% | K/9 |

|---|---|---|---|

| MacKenzie Gore | 3 | 29.7% | 11.18 |

| Cole Ragans | 2 | 36.4% | 14.05 |

| Zack Wheeler | 2 | 33.4% | 11.53 |

| Edward Cabrera | 2 | 24.9% | 9.41 |

| Kodai Senga | 2 | 24.2% | 8.81 |

| Reese Olson | 2 | 23.6% | 8.71 |

| José Soriano | 2 | 20.0% | 7.73 |

| Cade Horton | 2 | 17.6% | 6.79 |

MacKenzie Gore leads the way with three of these elite bat-missing weapons, followed by a few of the game’s best strikeout artists. At the bottom, though, are two pitchers whose strikeout rates are much lower than you’d expect given their ability to generate whiffs: groundball specialist José Soriano and rookie Cade Horton. (As an aside, Horton’s changeup has the third-highest whiff rate of any pitch thrown at least 100 times this year, yet his strikeout rate is an unimpressive 17.6%.)

What happens if you lower the threshold to pitches with whiff rates north of 30%? There are 18 starters with three or more of these less-effective-but-still-impressive pitches. Spoiler: Soriano shows up again.

| Player | Pitches With >30% Whiff% | K% | K/9 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zack Wheeler | 4 | 33.4% | 11.53 |

| Cole Ragans | 3 | 36.4% | 14.05 |

| Hunter Brown | 3 | 31.2% | 10.89 |

| MacKenzie Gore | 3 | 29.7% | 11.18 |

| Michael King | 3 | 28.4% | 10.35 |

| Jacob Lopez | 3 | 28.0% | 11.13 |

| Paul Skenes | 3 | 27.8% | 9.71 |

| Jesús Luzardo | 3 | 27.7% | 10.74 |

| Robbie Ray | 3 | 26.2% | 9.56 |

| Freddy Peralta | 3 | 25.5% | 9.41 |

| Spencer Schwellenbach | 3 | 24.9% | 8.78 |

| Bryan Woo | 3 | 24.3% | 8.58 |

| Clarke Schmidt | 3 | 23.1% | 8.35 |

| Hayden Birdsong | 3 | 22.8% | 9.32 |

| Noah Cameron | 3 | 21.7% | 7.70 |

| Tanner Bibee | 3 | 20.5% | 7.68 |

| José Soriano | 3 | 20.0% | 7.73 |

| Michael Wacha | 3 | 18.1% | 6.83 |

Here we see a bunch more of the best strikeout pitchers in baseball. Soriano is joined by rookie Noah Cameron, the struggling Tanner Bibee, and the wily veteran Michael Wacha as the outliers. For the most part, if your pitch mix includes multiple pitches that can rack up big whiff rates, you’re likely going to see a high strikeout rate to match. That makes Soriano a particularly glaring outlier.

A month ago, Michael Baumann investigated the curious case of the high-velocity pitchers on the Angels and their lower-than-expected strikeout rates. Jack Kochanowicz and Soriano were featured in that article as examples of guys with above-average velocity who just couldn’t strike anyone out, but the latter actually has the bat-missing weapons that the former doesn’t really possess. That warrants some further investigation.

The first thing you should know about Soriano is that he’s leading the majors in groundball rate by a pretty hefty margin. His 67.6% groundball rate is six percentage points higher than that of the next pitcher, Andre Pallante, and it is up nearly eight percentage points from where it was last year. He just recently set a single-game record for groundballs induced. All of this is seemingly by design, as he has increased the usage of his sinker by a little more than four percentage points this year, and it now makes up more than half of his pitch mix.

“I love throwing my sinkers because they go through the innings quicker, with less pitches,” Soriano said in an April interview with Jeff Fletcher of the Orange County Register. “I’d rather do that than have more pitches and more strikeouts.” He’s currently averaging 3.79 pitches per plate appearance, 17th among 59 qualified starters. His approach is to quickly work through the lineup, generating tons of contact on the ground with his hard sinker, and turning to his secondary pitches as, well, secondary options.

The easy answer is that batters simply don’t see enough pitches against Soriano for him to be able to rack up big strikeout totals; they put the ball in play before they can be sent back to the dugout on strikes. A little under 30% of all pitches in the majors have come with two strikes, while just 26.7% of Soriano’s pitches have come in such situations. He isn’t giving himself enough opportunities run high strikeout totals.

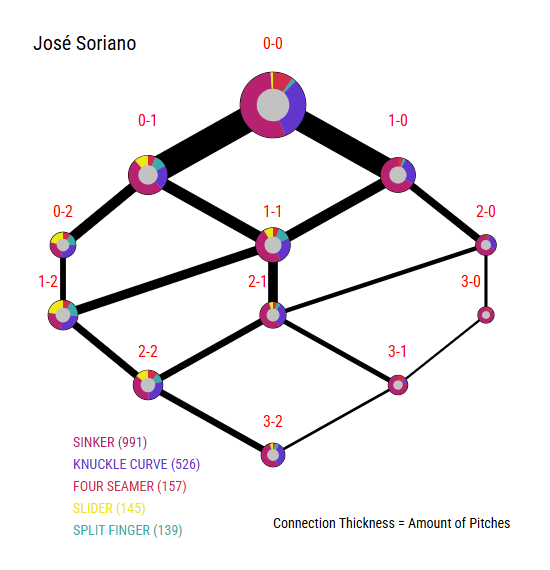

But what happens when Soriano does get to two strikes? Here’s a look at his pitch mix without two strikes and how it changes once he gets there, as well as a web graph showing his usage in each count.

| Pitch Type | Usage Before Two Strikes | Usage With Two Strikes |

|---|---|---|

| Sinker | 56.8% | 33.5% |

| Curveball | 26.2% | 28.7% |

| Four-Seamer | 7.7% | 8.8% |

| Slider | 4.1% | 16.5% |

| Splitter | 5.2% | 12.5% |

As you can see, Soriano heavily favors his sinker early in the count but starts to sprinkle in his slider and splitter with two strikes. The usage of his three non-fastballs with two strikes adds up to just 57.7%, so even when the count dictates trying to get a swing-and-miss, he still relies on his hard stuff more than 40% of the time.

Getting opportunities to use his secondary pitches is one thing, but is he using them effectively when he does throw them? Here’s a look at some of his underlying plate discipline metrics by pitch type.

| Pitch Type | Zone% | Two-Strike Zone% | Swing% | Two-Strike Swing% | Whiff% | Two-Strike Whiff% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sinker | 57.7% | 52.6% | 49.3% | 65.7% | 17.3% | 16.5% |

| Curveball | 44.9% | 38.0% | 35.9% | 60.7% | 42.3% | 35.2% |

| Four-Seamer | 54.8% | 50.0% | 41.4% | 65.2% | 25.8% | 23.3% |

| Slider | 32.4% | 36.0% | 55.2% | 60.5% | 43.8% | 40.4% |

| Splitter | 24.5% | 15.4% | 43.9% | 38.5% | 35.5% | 32.0% |

The biggest takeaway from that big table is that batters are swinging more frequently at each of his pitch types once the count reaches two strikes, but they are whiffing on those swings less often than they do earlier in the count.

It’s pretty easy to parse what’s going on with his splitter. He doesn’t throw it in the zone much, and he does so even less with two strikes. Some of that could be intentional, as pitchers typically use their splitters to get batters to chase, especially with two strikes. But it’s clear he struggles to command that pitch when you look at where he is missing. A third of his two-strike splitters end up in one of the easy-to-take locations that Statcast defines as the waste zone. He’s earned exactly one swing and one whiff on those wasted splitters.

It’s a little harder to figure out what’s going on with his curveball, which he throws more often than any of his non-fastballs and is extremely effective before two strikes. Interestingly, the Stuff+ grade on his curveball dropped to 73 this season, down from 104 in 2024. It’s hard to determine why the model has soured on the pitch, considering opponents are performing worse against it than they did last year (.270 wOBA/.251 xwOBA in 2025; .300 wOBA/.262 xwOBA in 2024). Perhaps the model is picking up something related to how his curve interacts with the rest of his arsenal.

When you look at his release point data, his curveball sticks out from the rest of his repertoire; its vertical release point is two inches higher than his sinker, and the horizontal release point has a three-inch difference. The release angle on the curveball is about six degrees higher than his sinker, too. Those are pretty small differences, but they could be enough for batters to detect as he’s throwing. The curve is nasty enough to generate an elite whiff rate on its own — its velocity is in the 93 percentile for the pitch type and its horizontal break is well above average — but as batters bear down with two strikes, perhaps that slight release difference is enough for them to be just a little more discerning.

Soriano obviously feels comfortable using his sinker as an out pitch with two strikes, even if that means fewer strikeouts. It seems like it’s an intentional approach that values quick work and groundballs in play, rather than aggressively hunting for whiffs. It’s important to note that the Angels currently have the worst team defense in baseball per OAA, with their infield ranking 27th in baseball by that same metric. An approach so heavily focused on allowing contact, no matter if it’s pounded into the ground, seems like a poor decision given the defense that’s behind him. That’s a big reason why his BABIP allowed is .317 this year and his ERA is nearly half a run higher than his FIP.

I don’t think simply throwing his secondary pitches more often will solve all his problems either. He clearly has trouble locating his splitter, and his curveball has that release point issue, which stems from his mechanics rather than his approach. His slider seems like the only secondary pitch that maintains its effectiveness no matter when he throws it. I do think that working to earn more whiffs with his breaking balls is probably a better approach than relying on the poor defense behind him. Even with their issues, his breaking balls still possess elite whiff rates, and it’s a shame he isn’t taking advantage of those weapons more fully.

Jake Mailhot is a contributor to FanGraphs. A long-suffering Mariners fan, he also writes about them for Lookout Landing. Follow him on BlueSky @jakemailhot.

This has me thinking outside the box. Looking at Soriano’s spray chart and his very extreme GB tendencies, could the Angels employ a “legal” 5 man infield by having an OF, we’ll call him Chris Taylor, play as a short rover depending on batter and situation? Perhaps this could mask some defensive shortcomings. The risk is obvious by having only 2 OF’s, but again, the spray chart suggests that might be a worthwhile trade off. Or is this just too crazy to even consider?