Kenta Maeda Has Made a Lot of Mistakes

Last week, you may have noticed that Kenta Maeda prominently featured in a Matthew Roberson article on this site, though probably not in the way he would have liked. He was the guy throwing the pitches that led to the “nearly 900 feet of home run” that Franmil Reyes hit. Maeda has been on the business end of a lot of home run highlights so far this year. He’s already given up seven of them after only surrendering nine last year in three times the number of innings pitched.

This is the same guy who finished second in AL Cy Young voting last season and allowed a stingy .219 wOBA (97th percentile). This year things are quite different, as Maeda carries a 6.56 ERA, a 6.16 FIP and a 4.19 xFIP through his first five starts. That 97th percentile wOBA from last season? Well it’s in the fourth percentile this season at .439. You might look at his elite walk rate of 4.5%, his swollen HR/FB rate of 26.9% and his soaring .372 BABIP and think that this is just a bit of bad luck. He’s not going to end the season having more than a quarter of his fly balls go for homers. But there’s more than just bad luck going on here. Maeda is getting hit extremely hard. He’s already allowed as many hard hits (95 mph or higher) in 2021 as he did all of last season and his xERA (the newest ERA estimator found here at FanGraphs, courtesy of Statcast) is 5.17.

So what’s going on? If you came into this article knowing anything about Maeda, it might be the fact that he has a great slider. According to our pitch values, it’s hard to find one better. Maeda’s was the sixth best slider in baseball from 2016-20. Here are his pitch values on his four main offerings throughout his career, with usage thrown in as well.

| Year | Fastball | Slider | Curveball | Changeup |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 4.8 (42.9%) | 19.1 (28.8%) | -6.4 (17.9%) | 4.4 (10.4%) |

| 2017 | 3.9 (43.5%) | 6.3 (25.0%) | 0.6 (14.1%) | -5.7 (9.0%) |

| 2018 | -2 (44.4%) | 6.7 (27.5%) | -5.8 (11.4%) | 7 (15.2%) |

| 2019 | 0.2 (37.4%) | 19.0 (30.8%) | 0.8 (7.3%) | 4.3 (23.8%%) |

| 2020 | 7.3 (25.9%) | 5.8 (39.9%) | 0.8 (3.4%) | 7.8 (28.9%) |

| 2021 | -5.5 (29.9%) | -7.3 (42.1%) | 0 (3.7%) | -0.9 (24.3%) |

Over the years, he has become more reliant on his plus slider and this year is no different, as he’s throwing it at a career-high rate. But the pitch has betrayed him completely. All of his pitches have struggled, mind you, but because the slider has been his most consistent pitch throughout his career, I think it’s worth focusing on.

The problem begins with his lack of command. It’s just not going where he wants it to go. The previously mentioned Franmil Reyes homer is a perfect example of this.

How about nine more examples?

None of those sliders were supposed to go where they did. (If you’re in the mood for a little game, there is one whiff hidden among those nine sliders as a reminder that baseballs are hard to hit, even when thrown right down the middle.)

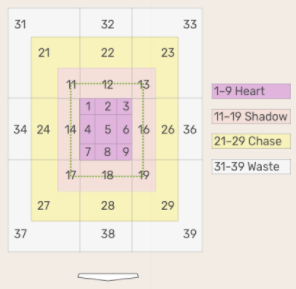

Baseball Savant classifies pitch locations with fun names like, the “heart,” “shadow,” “chase” and “waste.” Here’s a quick image of those locations as a reminder or if you are new to the concept. As you can imagine, all of those pitches you’ve seen so far were in the heart.

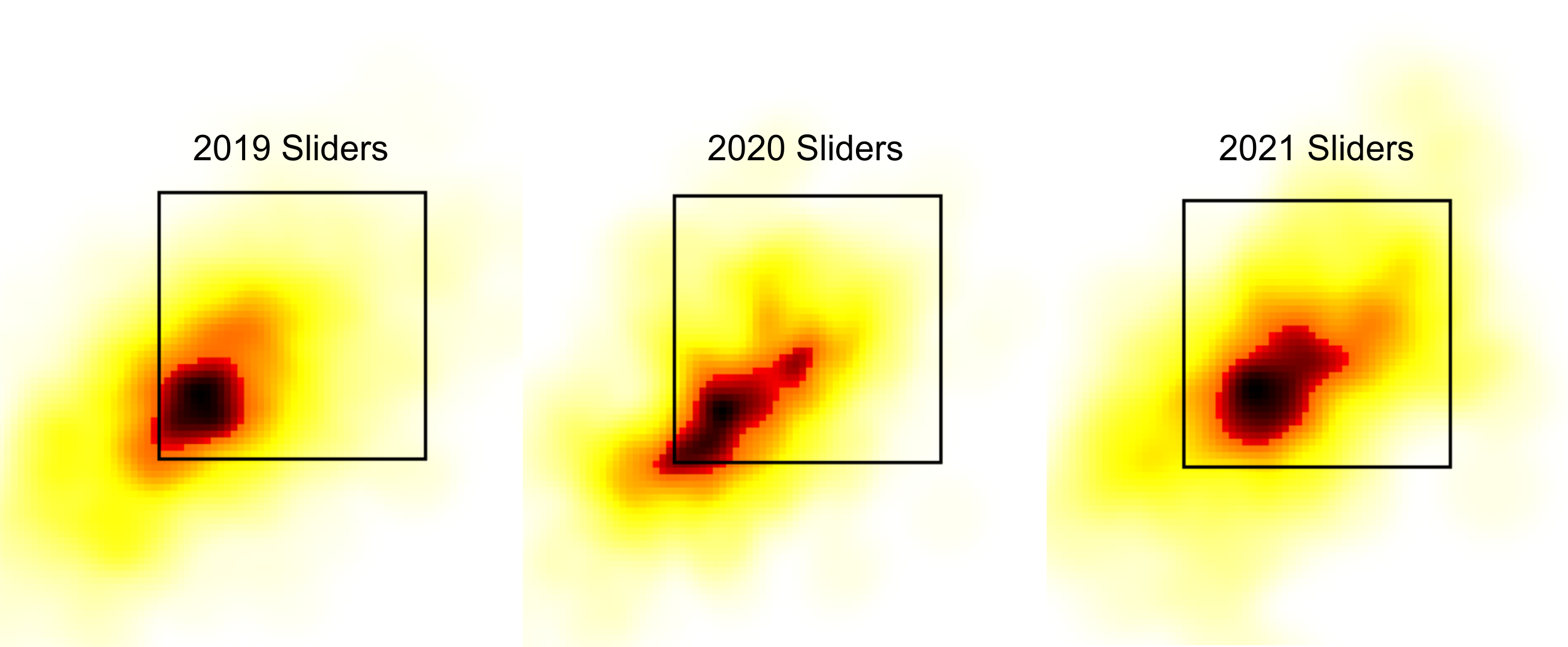

The difference between throwing your slider in the heart of the zone as compared to the shadow is massive. League-wide, hitters have a .357 wOBA on sliders in the heart of the plate while only a .206 wOBA on sliders thrown in the shadow. It’s essentially the difference between pitching to Trea Turner and pitching to John Smoltz. Maeda’s heat maps over the last three years show a pitch that is finding itself in the middle of the plate much more often than in the past.

To put numbers on those maps, he’s thrown 34% of his sliders in the heart of the plate this year (the league average is 24%). Back when his slider was at its peak in 2019, that number was 23.9%. Maeda’s 34% rate this year is the third highest heart percentage in baseball among pitchers who have thrown at least 100 sliders. He’s paying a hefty price for his missed location as well, with a .723 wOBA allowed on those pitches. The results have been worse than the quality of contact (he has a .484 xWOBA), but he’s still getting hit harder in that area than you would expect.

The heart of the plate is actually rather big, so I decided to cut it down to find the truly disastrous locations. If you look just at region 5 on Savant’s attack zone, you find that Maeda has thrown 15 sliders there, or about 10% of them. You’ve already seen screenshots from a lot of those pitches. I realize that we are whittling a small sample down to an even smaller sample but these are very important pitches. Their outcome determines whether the broadcast says, “He got away with one there” or “He hung one and look what happened.” Replays will be shown; the term “cement-mixer” will almost certainly be uttered. These pitches are clearly mistakes. Those happen to any pitcher but they’ve been happening too often for Maeda. If you are a fan of train wrecks, check out this sequence to Matt Olson. Here are the five sliders Maeda threw him in the at-bat.

He had count leverage on all of those pitches. The second slider was a good pitch but the location of all four of the others varied from not great to very bad. This year, that part of the zone has been particularly painful for Maeda. His dead center sliders have allowed an .899 wOBA (.709 xwOBA). Last year in his breakout campaign, he allowed a slightly less disastrous .535 wOBA on these mistake pitches. And believe it or not, he only allowed a .204 wOBA (.247 xwOBA) on dead center sliders in 2019.

This is where we have to start wondering whether there is more to his slider issues than merely missing his location. Even when we isolate it to only look at these dead center sliders, they’re still getting hit much harder than before. I imagine that part of this is simply bad luck and the small sample. Hitters do miss mistake pitches and I would expect Maeda to start getting a bit more lucky on his mistakes moving forward. However, the quality of stuff matters when you’re making mistakes and if Maeda’s stuff has diminished, that could help explain why his bad sliders aren’t sneaking by hitters as often. There is nothing in Maeda’s velocity to account for the pitch’s struggles. It’s down a hair but he’s succeeded at this velocity before. Likewise, his release point isn’t showing anything weird. His fastball and slider are still coming out of the same slot just like they always have.

I’ve shown you far too many bad pitches from Maeda. Looking at the good version of his slider can help us figure out what’s different about it from 2019.

My naked and un-scoutly eye is having trouble seeing a huge difference. Maeda has yet to pitch at a stadium where he pitched in 2019, so the different camera angle makes it tough. Let’s check out his movement numbers on our pitch type splits tab.

| Year | xMov | zMov |

|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 2.6 | 2.3 |

| 2020 | 1.9 | 2.5 |

| 2021 | 2.8 | 0.8 |

The different stadium cameras must be messing with my zMov-O-Meter because his slider is different this year and I couldn’t really tell.

If you aren’t too familiar with these pitch movement numbers, a fancy 12 to 6 curveball will have a negative zMov, meaning it is dropping a lot. Tyler Glasnow, for example, has a zMov on his big bender of -12.1. The closer you are to zero, the flatter the pitch is. Positive zMov will be really flat, like a fastball or a cutter. Maeda’s slider has always been fairly flat with a similar amount of horizontal and vertical movement. This year, however, his slider is dropping more. And a slider dropping more isn’t necessarily a good thing. Statcast takes pitch movement on pitches and translates them to league average. The new drop on Maeda’s slider has actually made the pitch more average. Throughout his career, his slider has dropped between five and eighth inches less than league average. This season it’s only dropping 2.7 inches less than league average. Average movement on a pitch is not what you want because it’s less weird in the eyes of hitters. And weird is good. In previous years, the flatness of his slider actually made the pitch unique, likely a factor in its success.

Maeda can’t survive throwing 34% of his sliders in the heart of the plate, especially if the movement on said slider is more conventional than in years past. Given that there aren’t any glaring velocity issues with Maeda, getting him back on track might be a relatively simple fix. In the meantime, you can also expect him to have some better luck when it comes to the mistakes he is making.

Luke Hooper is a designer and writer at FanGraphs. He lives in Portland, Oregon, longing for a major league team to materialize.

This is a kick-ass article. After his phenomenal 2020 sprint season and very good spring training stats, I was expecting Maeda would stay in the groove. Instead, he has been beaten up fairly regularly in the 1st month of 2021. Thanks for illuminating the problem with his slider. Maeda is fun to watch when he is on. I hope he can rediscover his magic . . .

This is why I am convinced there is some pitch tipping issue here. He was awesome as recently as spring training! Then suddenly guys are teeing off on his signature pitch. Not getting away with mistake pitches at an average rate seems like another good symptom that the batter knows what is coming.

Pitch tipping was something I was definitely planning on looking at more video on. In the end, I was satisfied with the fact that the slider just isn’t moving in the same way. If the movement was the same I’d be more inclined to think tipping is the main culprit.

I’ve done my best to look for any pitching tipping and couldn’t find anything, but it has really seemed at times this year that even when he does throw a good slider or splitter just outside of the zone, hitters are not even close to offering at it. The only other thing that comes to mind is the new baseball and the weather. Last years truncated season occurred during the summer and spring training this year also had warm weather. Every start of his this year aside from opening day in Milwaukee has been in weather that has been sub 60F (even in Oakland where it was 57F.) Obviously a factor we would never know without the player saying it himself, but I’m intrigued to see what happens to his pitches as the weather warms up.