Less Slappin’, More Whappin’

Count me among the multitudes who have been borderline obsessed with the emergence of Pete Crow-Armstrong as a superstar this season. I’m sure he’ll reach a saturation point eventually where hardcore fans get tired of him — it happened to superhero movies, and bacon, and Patrick Mahomes — but we’re not there yet.

Every time I write about PCA, I revisit the central thesis: This is a player who’s good enough to get by on his glove even if he doesn’t hit a lick. But out of nowhere, he’s turned into a legitimate offensive threat. Great athletes who play with a little flair, a little panache, a little pizzaz, tend to be popular in general. The elite defensive center fielder who finds a way to contribute offensively is probably my favorite position player archetype; the more I compared PCA to Lorenzo Cain, Jackie Bradley Jr., Enrique Bradfield Jr., Carlos Gómez… the more I understood why I’d come to like him so much.

In fact, let’s take a moment to talk about Gómez, and his offensive breakout in the early 2010s.

Gómez was the prize young player who went from the Mets to the Twins in the Johan Santana trade. The book on Gómez back then was speed, speed, speed. He stole 12 bases in 58 games as a 21-year-old rookie, and quickly developed into an elite defender in center field. But even after the Twins sent him to Milwaukee for J.J. Hardy two seasons later (I go on and on about it, but this guy has such a fascinating trade history), Gómez didn’t hit for either average or power. Even with an extremely limited offensive game, he was an average player, but nothing more.

Then, one day, Gómez woke up and realized that he was 6-foot-3 and 220 pounds. He didn’t have to just ground-and-pound to take advantage of his speed; he could hit the ball in the air as well. The result: batting averages in the .280s and 20-plus homers a year. And because nothing about the new approach prevented Gómez from playing defense or stealing bases, he did all of that while continuing to steal 30-plus bases a year. The result: 6.7 WAR in 147 games in 2013, and 5.7 WAR in 148 games in 2014.

Gómez’s emergence set in motion a chain of events that culminated in one of my favorite clubhouse anecdotes of the 2010s. Not long after the Brewers signed their star outfielder to a three-year, $24 million contract, Sports Illustrated writer Luke Winn profiled Gómez and included the following:

[Ryan Braun] says that recently Gómez informed him, while holding a plate full of kiwi, that the fruit had three times as much potassium as bananas. “I asked him how he heard it,” Braun says. “He told me, now that he’s wealthy, he’s been Googling rich-people conversations so he knows what to talk to wealthy people about, and he came across that data.”

Back to Crow-Armstrong: In 2024, he had a GB/FB ratio of 0.88, which was hardly a Nellie Fox tribute act to begin with. This year, his GB/FB ratio is 0.48. The guy with 97th-percentile sprint speed is putting the ball in the air more often than any qualified hitter except for Cal Raleigh, who is so slow any attempt to quantify his sprint speed defies the limits of contemporary mathematics.

It got me thinking: Who’s next? Which fast guys are pigeonholing themselves into a groundball-heavy approach, and thus denying themselves the pleasures of the lucrative and kiwi-filled dinger-bashing lifestyle?

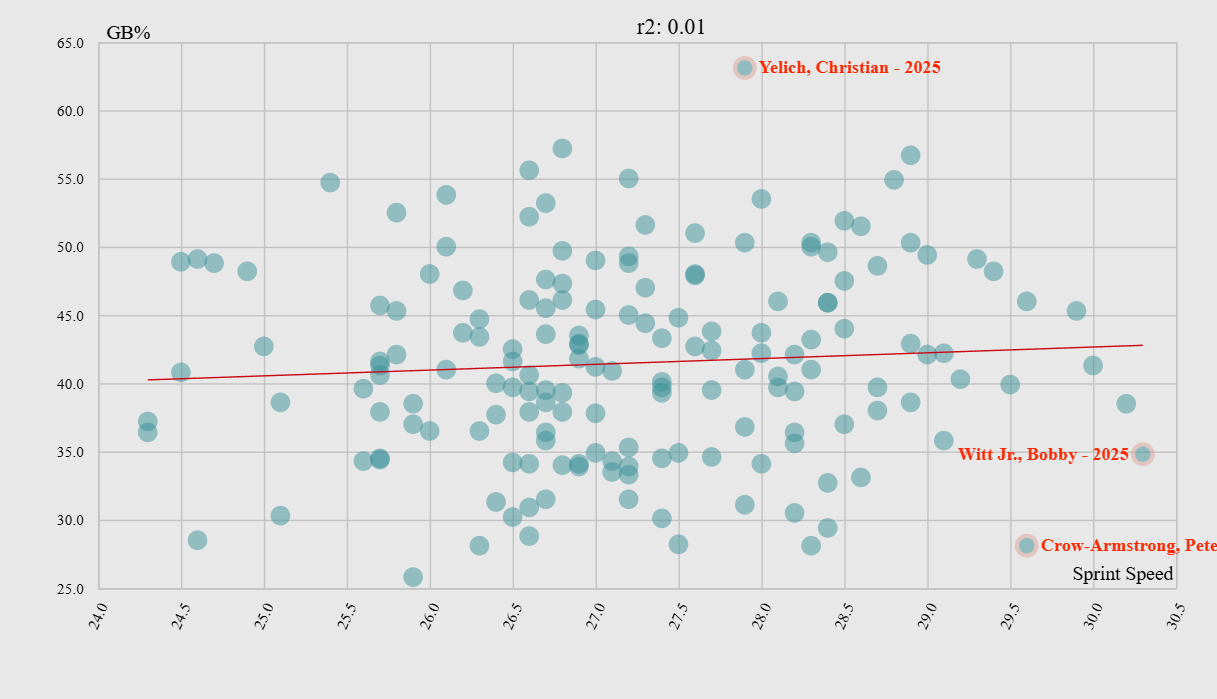

I rustled up this little chart on Baseball Savant. As you can see, there’s no correlation between sprint speed and groundball rate. What I want to see is whether anyone can be moved from the top right quadrant of the graph to the bottom right.

Some of these cases are pretty well documented. Like, we all know Christian Yelich and Vladimir Guerrero Jr. both hit the ball on the ground too much. So out of all qualified hitters, I took those who were at least one standard deviation above the mean in both sprint speed and groundball rate. Then I fiddled with the criteria a little because I wanted to get Dylan Crews into the sample. (One standard deviation above the mean for GB% was 48.6%, which left Crews four tenths shy of making this table. Also: This table uses Savant’s batted ball type classification; our numbers are slightly different, but this exercise isn’t scientifically rigorous enough to split hairs over.)

| Name | Team | GB% | Sprint Speed (fps) | EV50 (mph) | BABIP | wOBA | xwOBA | wRC+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dylan Crews | WSN | 48.2 | 29.4 | 101.3 | .233 | .277 | .343 | 74 |

| Julio Rodríguez | SEA | 49.1 | 29.3 | 102.9 | .264 | .329 | .364 | 119 |

| Brice Turang | MIL | 49.4 | 29.0 | 100.1 | .342 | .317 | .347 | 101 |

| Elly De La Cruz | CIN | 56.7 | 28.9 | 103.6 | .324 | .336 | .336 | 107 |

| Sal Frelick | MIL | 50.3 | 28.9 | 96.7 | .310 | .332 | .316 | 111 |

| Fernando Tatis Jr. | SDP | 54.9 | 28.8 | 104.1 | .295 | .368 | .387 | 139 |

| Ceddanne Rafaela | BOS | 48.6 | 28.7 | 100.9 | .269 | .270 | .335 | 65 |

| Jackson Holliday | BAL | 51.5 | 28.6 | 101.0 | .320 | .323 | .336 | 112 |

| Gunnar Henderson | BAL | 51.9 | 28.5 | 104.9 | .339 | .337 | .322 | 121 |

Let’s dive into this set of nine players. Tatis, Rodríguez, and Henderson go into the “don’t mess with what’s working” group. And I say that even though Rodríguez and Henderson are, broadly speaking, having slightly disappointing offensive seasons. I’m sure they’d love to hit more doubles and home runs, but Rodríguez is putting up basically the same wRC+ he did last year despite some appalling batted ball luck, while Henderson’s issues are numerous.

There’s nowhere to go but down after an 8.0 WAR season, I suppose, but Henderson, in addition to not squaring the ball up as well, is whiffing more, chasing more, striking out more… all the bad stuff. His woes require their own blog post, and even then — he’s got a 121 wRC+ as a shortstop. That’s still really good by any reasonable standard.

Frelick has sixth-percentile bat speed and a 12th-percentile HardHit%; I don’t think there’s much untapped power there.

And until I dug a little, I would’ve said the same thing about Rafaela and Turang. Eight-year contract or no, Rafaela is running out of rope at the major league level for two reasons: First, he’s been absolutely terrible at the plate. Second, the Red Sox are calling up shiny position player prospects faster than they can clear spots in the lineup. As for Turang, I would’ve had him lined up as a Geraldo Perdomo-type low-bat-speed, high-contact guy, with a plus-plus baserunning tool.

But look, they’re both putting better swings on the ball this season.

| Name | Year | Fast Swing% | Barrel% | Ideal Attack Angle% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brice Turang | 2024 | 3.4 | 2.4 | 25.9 |

| Brice Turang | 2025 | 10.6 | 8.4 | 42.3 |

| Ceddanne Rafaela | 2024 | 6.8 | 7.5 | 52.6 |

| Ceddanne Rafaela | 2025 | 12.8 | 13.0 | 54.4 |

Turang is getting results; Rafaela has been hampered by some bad batted ball luck and, more worryingly, the fact that he will still swing at almost anything that comes in his direction.

That leaves Holliday, De La Cruz, and Crews.

After a nightmarish rookie season, I’m mostly relieved Holiday is showing any signs of life at all. The former no. 1 overall pick has nearly doubled his wRC+ and cut his strikeout rate by a third. Even with his impressive background, Holliday is an average-over-power hitter who topped out at 12 home runs in the minor leagues. He’s still so young I’d expect him to add power as he fills out, but his batted ball profile suggests that might just lead to harder-hit grounders, not home runs.

Here’s a number you might not expect: De La Cruz grounded into 12 double plays last year. That’s by no means a league-leading figure, but it’s a pretty big number. It’s as many as Raleigh and Brent Rooker hit into combined, and Elly can run from home to first in about four strides.

Why? Because hitting the ball hard on the ground can be perilous. If the ball doesn’t get through the infield, it just gets to the fielder faster. That gives the infielder more time to record the out — or sometimes both outs.

EDLC (I find, as with PCA, that being able to go by one’s initials is a boon for a budding young athlete) is actually hitting the ball on the ground more this year than at any point in his major league career. Worse, this propensity for grounders is coming at the expense of line drives; his LD% has dropped from 20.7% in 2024 to 10.7% this season.

Then there’s Crews, at which point I realized the folly of this exercise. Of course Crews should hit the ball in the air more. His groundball rate was pretty much the only flaw anyone found in his game when he was a three-year starter for one of the most highly scrutinized amateur teams in the country. He fell — “fell” — from first to second in the draft, behind his LSU teammate Paul Skenes, mostly because of signability concerns, but Crews’ groundball rate got talked about much like Skenes’ fastball shape: not ideal, but pointing it out feels like nitpicking, and maybe the rest of the package is so good it won’t matter.

It hasn’t for Skenes; it has for Crews. C’est la vie.

I went looking for the next Carlos Gómez and came out with three of the most thoroughly researched and picked-over prospects in the history of professional sports. Everyone knows they could stand to put the ball in the air more.

This isn’t the end of the elevate-and-celebrate movement, but I do think it’s hit a dead end in terms of being low-hanging fruit in player development. Statcast data doesn’t go back all that far, but in the first year of the sample, 2015, 16 out of 142 qualified hitters had a sprint speed of 28.46 ft/sec or better, and a GB% of 48.0% or higher. This year, as you’ve seen, those endpoints snag just nine qualified hitters out of 168.

In a decade, this has gone from the kind of insight that could change a 30-year-old’s career to a basic technical competency for every 16-year-old who’s ever seen a private hitting coach. Ten years doesn’t seem like a long time, but an innovation that successful gets adopted, copied, and built upon very quickly. It took less time than that to get from Chuck Berry to the Beatles. Now we’re in the age of rock and roll.

Michael is a writer at FanGraphs. Previously, he was a staff writer at The Ringer and D1Baseball, and his work has appeared at Grantland, Baseball Prospectus, The Atlantic, ESPN.com, and various ill-remembered Phillies blogs. Follow him on Twitter, if you must, @MichaelBaumann.

The other day on the reds broadcast Barry Larkin claimed that it’s great how many outs Elly is making on the ground because “with his speed it’s better than hitting it in the air”. Some of the stupidest baseball analysis I can remember.

Larkin is not a good analyst, I much prefer Chris Welsh. And yet, there is a significant chunk of the fanbase who has been clamoring for Larkin to be the manager for years now. A lot of that group probably also agreed with Marty that Votto walked too much.