Lourdes Gurriel Jr., Destroyer of Sliders

Lourdes Gurriel Jr. needed a reset. It was April 14, and he was hitting .175/.250/.275 over 44 plate appearances. After starting the season 2-for-27, he’d recorded hits in four straight starts, but the Toronto Blue Jays still saw enough significant problems to warrant time in the minor leagues. They sent him down to Buffalo, where he hit .276/.308/.480 with a 94 wRC+ in 31 games. It was a perfectly cromulent performance, but nothing that suggested he was a brand new man capable of wreaking havoc on big league pitching.

Then in his first game back in the majors on May 24, Gurriel hit his first homer of the season. The next day, he homered again, and the day after that, he homered again. He hit another three games later, was quiet for a week after, and then rattled off 10 homers in his next 18 games. That included back-to-back two-dinger performances last Wednesday and Friday. Since his return from the minors, no one in baseball has better numbers than Gurriel in homers (14), slugging percentage (.750), wOBA (.466), or wRC+ (199). Just three hitters have produced more WAR.

Gurriel’s hot streak is a surprise, though not because his talent has ever been in doubt. A native of Sancti Spiritus, Cuba, he was known in his young Havana Industriales career for being an athletic player with a nice glove, but he began to break out with the bat by hitting .344/.407/.560 in the 2015-16 season. That’s the kind of performance that will help put a player’s name on the map, but in Gurriel’s case, plenty of people already knew his name. His father, Lourdes Gourriel, is a former Cuban National Series MVP winner and won a gold medal with Team Cuba in the 1992 Olympics. Meanwhile, his older brother Yuli had already been a star in Cuba for the better part of a decade. Lourdes Gurriel Jr. definitely had strong baseball genes, and in November 2016, he signed a seven-year, $22-million contract with the Toronto Blue Jays, a team that has shown quite an affinity for signing players who come from prominent baseball families.

Gurriel was the sixth-ranked international prospect at the time of his signing according to MLB Pipeline, and our own Eric Longenhagen had him ranked at No. 7 in the organization the next spring. Because of his six years of professional experience, the Blue Jays chose an aggressive track for him, placing him in Double-A ball just 19 games into his stateside career. That proved to be more than the then-23-year-old could handle out of the gate, as he struggled through a .229/.268/.339 batting line across 64 games of High-A and Double-A in 2017. The following season, his promise began to shine through again, as he posted a 134 wRC+ in 14 games at Double-A before Toronto made another aggressive decision to bring him straight to the majors. Once again, he floundered, hitting just .206/.229/.309 in 20 contests before getting sent to Triple-A.

When Gurriel returned to the majors last summer, he did so a seemingly changed hitter. He homered in his first game back from the minors, and from July 11-29, he recorded a franchise-record 11 consecutive multi-hit games. He was the first rookie in baseball history to do so since 1911. After limping his way to a 43 wRC+ in his first 20 games, he finished his rookie year with a wRC+ of 103.

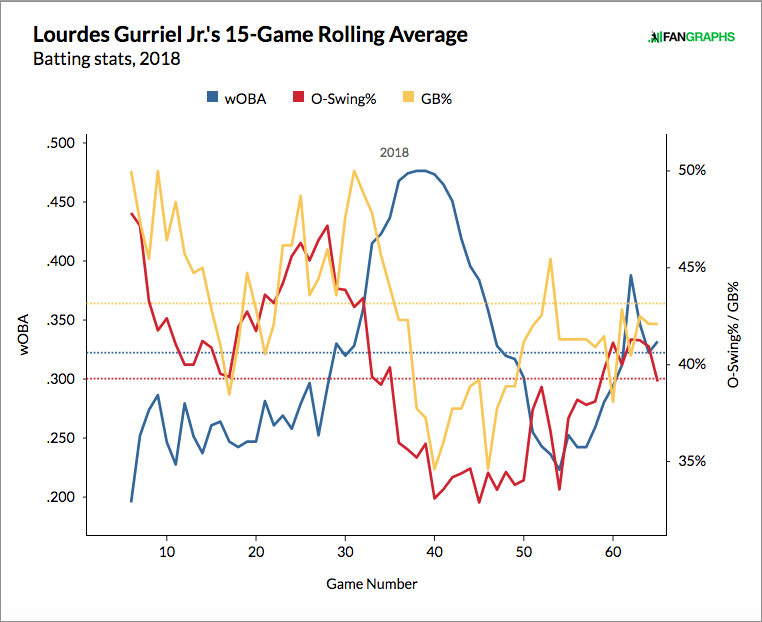

We have something of a pattern here. For two years in a row, Gurriel has landed in the big leagues early in the season. He’s struggled each time, been sent down to Triple-A, and returned as a legitimately imposing bat. Last year, the adjustments he seemed to make were rather straightforward: Only swing at pitches inside the strike zone, and hit them in the air.

It’s a fine plan to have, and the results showed quickly, but they didn’t stick around. At the start of 2019, his ground-ball rate soared again while his chase rate began to wobble up and down. Both of those figures have dropped as Gurriel has heated up again, but they no longer seem to be the defining force of his surge. Instead of working on improving a couple of weaknesses, he has turned one weakness into a pretty significant strength.

| Name | wSL |

|---|---|

| Lourdes Gurriel Jr. | 10.1 |

| Hunter Dozier | 9.6 |

| Xander Bogaerts | 9.1 |

| Adam Frazier | 7.1 |

| Charlie Blackmon | 7 |

| Scott Kingery | 6.9 |

| George Springer | 6.6 |

| Josh Bell | 6.6 |

| Eduardo Escobar | 5.9 |

| Tim Anderson | 5.9 |

Against sliders, Gurriel is hitting .356/.383/.933 in 2019. He has had had 45 at-bats end on a slider, and seven of them have been home runs. No one in the majors is doing more damage against the pitch.

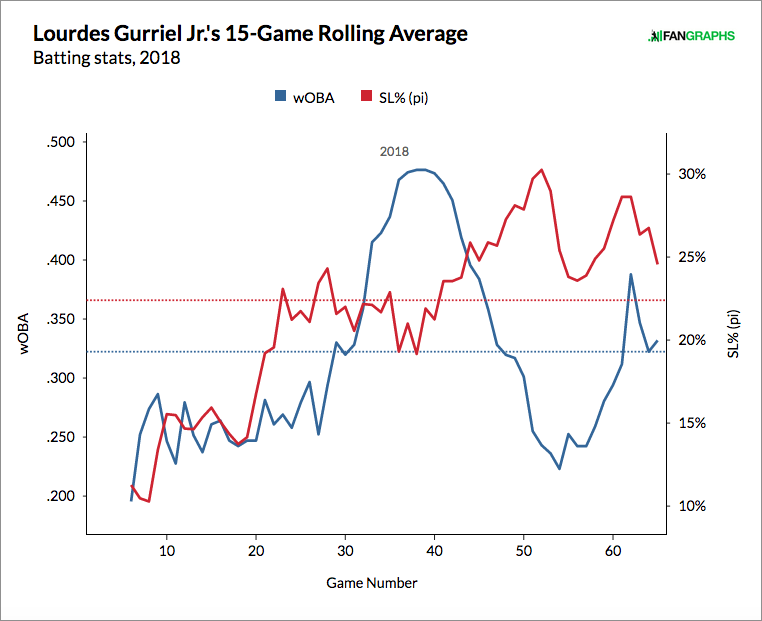

This is notable for a few reasons, the first of which is that Gurriel was not a good slider hitter last season. He posted a wSL of -3.4 in 2018, with an xwOBA of .212. In fact, the more sliders Gurriel saw, the worse he performed overall. This rolling average chart showing the relationship between the percentage of sliders seen and his wOBA is pretty damning.

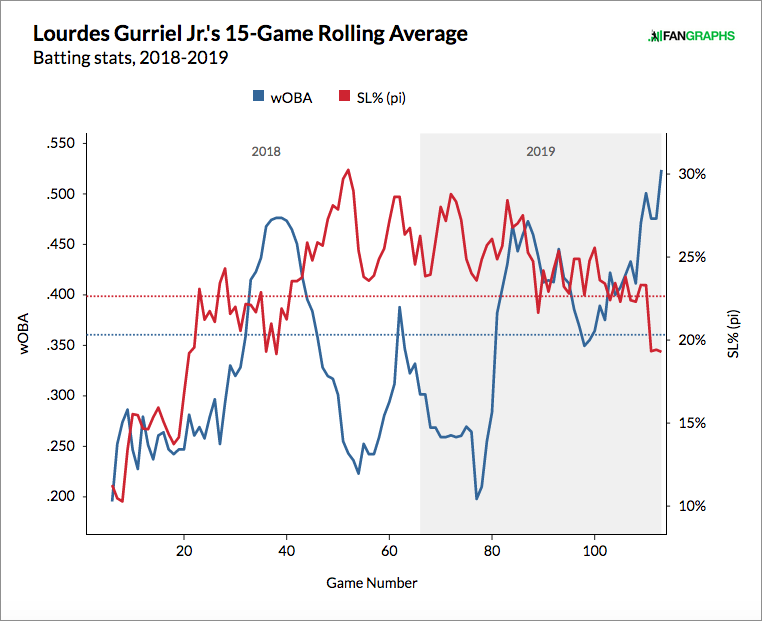

You can see right around the 40-game mark where things begin to go south for Gurriel. Near the end of his multi-hit streak, opposing pitchers began to bombard him with slider after slider, and his production absolutely cratered. By the time both lines reach their maximum separation, Gurriel is seeing sliders over 30% of the time, and his wOBA is down to .223. It’s easy to see the incentive he might have had to work on his ability to pick up the slider, and for the time being, it seems that he found that ability during his latest stint in the minors. Here’s the above chart with the 2019 season added onto it, with Gurriel’s latest promotion happening around the 80-game mark.

As you might imagine, Gurriel hasn’t done this kind of damage against sliders without getting to pummel a couple of cement mixers, like this one from Brad Peacock:

But while he has certainly benefited from a few hangers, it seems unfair to call this run of success a fluke. Here, for example, is Gurriel yanking a slider below the knees from Robbie Ray 414 feet to left field.

And here he is driving another low slider off the center-field wall, this time against Chaz Roe.

That’s a pretty good pitch. Plenty of drop, starting high enough so that it’s a strike until the very last few feet. But Gurriel waits for just the right moment to swing, and an 80.3-mph offering leaves his bat at 104.7 mph.

This isn’t a perfect fix yet. Gurriel’s vast improvement against the slider has come at the expense of his ability to hit four-seamers, against which he holds an xwOBA of .296 in 2019 after posting a .406 figure a year ago (though he mitigates this a bit by hitting sinking fastballs very well). He’s also still the same hitter against other secondary offerings, such as the curveball and the changeup, that he was a year ago. And while he’s improved his walk rate from its ghastly minor league track record, it still sits at just over 6%, which won’t play well with a strikeout rate exceeding 25%. For now, however, this is a step forward in his game that is obviously working for him. Time will tell if it’s part of a grander stride toward consistency in the big leagues.

Tony is a contributor for FanGraphs. He began writing for Red Reporter in 2016, and has also covered prep sports for the Times West Virginian and college sports for Ohio University's The Post. He can be found on Twitter at @_TonyWolfe_.

Once every batter starts sitting slider, they will function like bad fastballs.

Gotta be able to recognize slider, which too many batters aren’t able to do. Been the death of many a “good” prospect.