Meet the Rays’ Latest Starting Pitcher

By now, you know how the Tampa Bay Rays operate: Due to their small budget, their success hinges on whether they can replace formerly cost-controlled and talented players with currently cost-controlled and talented players. The process works (even as we wish they would flex their financial muscle more often), and the Rays have been to every postseason since 2019.

But inevitably, the Rays’ way results in a few bumps in the road. Sometimes, prospects or trade acquisitions don’t pan out as hoped. This season in particular, their rotation has suffered a spate of injuries. Shane Baz is injured. Luis Patiño is injured. Tyler Glasnow might miss the entire season. As for internal options, Josh Fleming failed to impress as a starter and was recently optioned to Triple-A Durham. Fortunately, the Rays always seem to materialize at least one good player out of thin air each season. Their latest trick? Making a starter out of Jeffrey Springs.

What’s surprising is that unlike Fleming, Springs had virtually zero prior experience starting in the big leagues, save for two opportunities in his rookie year. Nonetheless, his workload has begun to increase. He tossed 4.2 innings against the Blue Jays on May 15, followed by 5.2 innings against the Orioles on May 21. And in his latest start, Springs pitched a full six innings, striking out six Yankees while giving up just two runs. But it was their B-squad! I know, yankeesfan0567. But what matters to the Rays is that Springs passed with flying colors, his spot in the rotation now all but entrenched.

Why Jeffrey Springs of all people, you might ask? Let’s hear from the man(ager) himself, Kevin Cash:

“Certainly, it’s interesting to talk about. He hasn’t done it in a long time, to become a starter/bulk guy. But being so tough on righties, and being as good as he’s been, it makes the conversation fun to have.”

Springs is a lefty. But as Cash mentioned, that doesn’t mean he’s an easy target for right-handed hitters. That’s because they have to deal with his changeup. In fact, if you were to look for the biggest change Springs has made this season, you’d come across his changeup usage, which is up to 39.3% after a 27.8% mark last year.

There’s been a commitment to the changeup because it is, without a doubt, Springs’ best pitch. The decision itself is nothing new, but what’s different in this case is that it’s a matter of command, not stuff. The movement Springs imparts to his changeup isn’t outrageous, nor is it terribly fast. But it’s amazing just how consistently the pitch is located down and away. When Springs hits his spot, which is often, major league hitters tend to do this:

And on occasion, they will also do this:

I mainly put that second GIF in for the laughs. Bo Bichette’s swing decisions aren’t great overall, and he didn’t look sharp that day. Still, if not for his reputation as a slow ball whisperer, Springs probably doesn’t earn that whiff. One reason why changeup-first pitchers might be shunned in the modern game is because when located down the middle, offspeed pitches allow a higher wOBA compared to breaking balls or fastballs. There’s less room for error, in other words. But owing to his command, Springs serves up very few meatballs – his rate of middle-middle changeups (10.6%) ranks seventh-lowest among pitchers who’ve thrown a change at least 100 times. And even when hitters do make contact against Springs’ changeup, they don’t accomplish much.

Of course, a good changeup doesn’t exist in a vacuum. It needs to play off the fastball in order to fool hitters, and the success Springs is enjoying can be partially attributed to his heater. Once again, the stuff isn’t amazing – Springs sits 91-92 mph and generates slightly above-average vertical movement – but he arguably has the best fastball command of any lefty this season. Hyperbole? Not really! We can find the evidence, too. What Springs does exceptionally well is place his heaters up and away, where left- and right-handed batters alike have trouble. Limited to lefty pitchers, here’s a table of this season’s leaders in up-and-away fastball rate:

| Pitcher | Pitch% |

|---|---|

| A.J. Minter | 55.3% |

| Jeffrey Springs | 55.1% |

| Reid Detmers | 52.8% |

| Caleb Thielbar | 51.0% |

| Brent Suter | 49.3% |

| Madison Bumgarner | 48.8% |

| Tarik Skubal | 48.2% |

| Carlos Rodón | 47.2% |

| Zach Logue | 47.1% |

| Justin Steele | 46.1% |

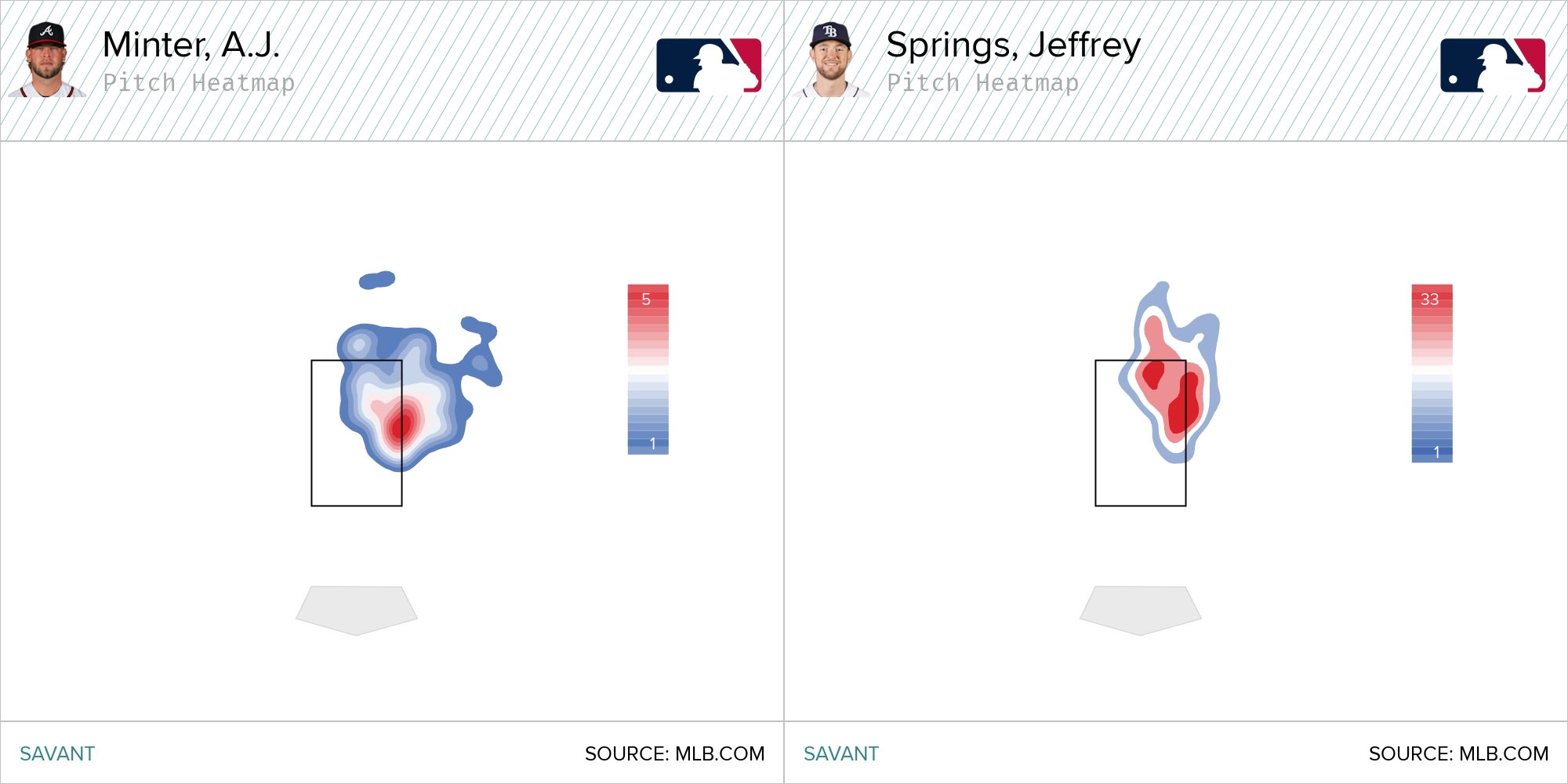

This is a diverse cohort, ranging from dominant lefties like Carlos Rodón and Tarik Skubal to crafty relievers like Brent Suter and Caleb Thielbar. At the top is A.J. Minter, who’s having a fantastic season, with our protagonist close behind. Overall, while imperfect, the table passes the smell test. But do you know what separates Springs from Minter? Consider this side-by-side comparison of where their up-and-away fastballs have actually ended up:

There’s a difference between sending a pitch towards a general vicinity and commanding it with pinpoint accuracy. Minter has been great, but for a different reason: His overwhelming stuff more than makes up for the fact that his fastball is all over the place. Meanwhile, you can see how Springs’ heat map is concentrated around the outer edges of the plate. When he throws a fastball, it seldom goes to waste. With that heat map in mind, you start to understand how Springs is capable of striking out someone like Aaron Judge, who usually has little trouble dealing with the hard stuff:

Eight times out of a 10, a hitter will either see a fastball or a changeup from Springs, both of which almost never leak out over the plate. That’s been the bulk of the formula, and it’s worked. But on the occasions when Springs does face a lefty batter, he’ll whip out his third pitch: a slider. It’s the least impressive of his troika stuff-wise, but – surprise, surprise – Springs’ command shines through. Here’s how the pitch typically looks:

Not much to add here! That’s what every southpaw wants to do with his slider: Make it run away from the barrels of left-handed hitters, which Springs has become better and better at as his career has progressed. Here it is worth noting that he’s dramatically altered the tilt of the axis on which his slider spins. Referencing a clock face, we can say the old slider (pre-2022) spun in the direction of 3:30; the new slider, meanwhile, spins in the direction of 1:45.

The result has been a breaking ball that drops less and moves more laterally than before. It’s not a sweeper, though, so Springs isn’t jumping on a bandwagon. And it’s unclear whether this represents an improvement. There’s been a loss in total movement, but the tricky thing about pitch design is that more movement isn’t necessarily beneficial. I supposed in instances like these, it’s best to trust Springs and the Rays. They came to the conclusion that a brand new slider shape would help. Maybe it really has.

The image you might have of a typical Rays pitcher is someone who relies on stuff over command. Springs, however, is the exact opposite, which makes him both a joy to watch and stand out compared to his staff mates – triple-digit fastballs are cool, but so are a series of perfectly located pitches that stymie an entire lineup. Moreover, Springs’ command has improved as a starter. It has helped him weather the predictable decline in strikeout rate that marks the transition from the bullpen to the rotation. The whiffs are down, but so are the walks. The multi-inning outings have looked as dominant as the single-inning ones.

Because Springs lays waste to righties, it’s possible teams will counter by sending forth more lefties, platoon advantage be damned. Sure enough, in that start against the Yankees, Matt Carpenter batted fifth. Fifth! But the decision paid off for New York: In the top of the fourth inning, Carpenter yanked a high fastball into right field for his first home run of the season. It was also one of just two runs the Yankees mustered against Springs, but that’s all it took. The Rays couldn’t score at all, and Springs took an unfair loss.

That’s not the entire story, though. Springs got to face Carpenter one more time, and like all good pitchers do, he made the adjustment. His first pitch was a slider. His second pitch was… also a slider. His third, fourth, and fifth pitches? Slider, slider, and slider. No reason to offer a fastball when your opponent is hunting for one. And on the sixth pitch of the at-bat, Springs got Carpenter to whiff at a two-strike slider, ending the outing on a high note:

As of this writing, Springs has a 2.35 ERA, a 3.44 FIP, and a 20.7% K-BB% as a starter. Those are numbers that stand to worsen in a larger sample, but the Rays aren’t hoping for an ace. And already, Springs has exceeded expectations – his command has been pristine, and he’s demonstrated the ability to navigate the second and third times through an order. It’s enough to make the Rays likely feel much better about their rotation. Not everything has gone according to plan. But if not for Jeffrey Springs, it could have been worse.

Justin is an undergraduate student at Washington University in St. Louis studying statistics and writing.

The pitching has been great, despite all the injuries to 3 of their projected 4 top starters. If Tampa’s bats come to the party they could be very strong in the second half.

Nobody destroys arms like the Rays. It is not bad luck, it is what it looks like when you don’t value a player’s long-term outlook at all. Just for fun look at their team pitching stats from any other year – it has to be the highest turnover in the league. Within a year or two it is a graveyard of arms every time. They abuse pitchers and ruin their careers – that is their MO. Also, what bats? They don’t have a lot of offensive talent. They create platoon players that have short bursts of production but spend most of the season being bad. Great players don’t need to platoon, but TB isn’t trying to develop players. TB is literally a mediocrity factory – lucky for them half the league is not actively trying to win. They are competitive at the cost of grinding up the roster into hamburger but they are not far above average in terms of talent if at all. They seem to have played a super soft schedule so far – that is antecdotal but I think it is true. Then again, I can’t say that everyone isn’t playing a super soft schedule so far. I would bet on them having a worse second half.

You must really dislike the Rays. They have the 4th best record in baseball since 2008 with two World Series appearances.

For a team that destroys pitchers and doesnt have a lot of offensive talent, they sure have been good for, oh, the last fifteen years, in which they have won over 90 games eight times.

Ok but is he wrong? Ignoring the (considerable amount of) dicta, which the two above commenters rightly rebutted, is he wrong about the rays and pitcher injuries? I’d never thought about it, but is this kind of a 49ers running backs thing? Where the system works super well but inherently takes a toll on the purposely cheap and replaceable players?

One would think this would be measurable, and a pretty interesting thing to measure. I’m sure there’s a lot of ways to go about it, but I’d probably try something like:

-Identify all unique pitchers who have had, say, a 2 WAR season in the last ten years.

-Look at how many innings each pitcher pitched in the three years following their first 2 WAR season.

-Run averages based on the team that pitcher had their first 2 WAR season for, see if there’s anything interesting.

-Somehow adjust starters/relievers.

(I’m sure someone can come up with a better way.)

1. Pitchers are inherently risky.

2. Optimizing pitcher performance (which I would say the Rays do the best in baseball) and overusing pitchers are different things. Maybe someone else can do a deeper dive, but guys like Luis Patino, Drew Rasmussen, Blake Snell, etc. are all examples of guys who generally only get 80-90 pitches, 5 innings or two times through the order. You don’t really see that on other teams as often.

3. Part of optimizing said performance could be telling pitchers to throw max effort, which could in turn lead to more injuries. Also, the idea of throwing your best pitch. Sliders (and other breaking balls) are more likely to hurt your arm than fastballs. Guys like Matt Wisler, Diego Castillo, and Rasmussen have seen there fastball rates drop and breaking ball rates increase which could in theory lead to more injuries.

4. Rays do have a rotating door of pitchers relative to other orgs as they will usually trade their good pitchers usually by their 2nd or 3rd year of arbitration.

There probably is a little bit of truth to pitchers on the Rays get hurt more often, but it’s also hard to separate that from normal pitcher injuries imo. For example, Patino was already injury prone and the Rays acquired him from the Padres. Is it the Rays fault? Hard to say.

Yeah, this all makes sense. I guess it’s plausible that the Rays, knowing that (a) pitchers break and (b) they have no money and thus will never be giving their pitchers big contracts, are more likely to lean into the max-effort-5-and-dive or just throw your slider all the time type stuff. Which might lead to more injuries.

And since they’re so good at development and optimization, it doesn’t really hurt so much if/when somebody goes down, because they’ve likely already got more than fair value out of the player and have another one ready to step up.

I don’t think it’s nefarious at all but I do think the Rays probably have a more nihilistic view of pitcher health than other teams. Because of their constraints and capabilities it makes sense to get the most out of a pitcher, and since they’re never going to pay them big money and they have a million other guys it’s not the end of the world when they get hurt.

Tampa goes through pitchers rapidly because of financial considerations.