Merrill Kelly Returns From Whence He Came

Like Travis Henderson in 1984’s Paris, Texas, Merrill Kelly left his home, wandered across the desert, and ultimately realized he needed to head back where he came from. On Sunday morning, Ken Rosenthal reported that Kelly was finalizing a two-year, $40 million contract to return to the Arizona Diamondbacks.

Kelly is as Arizona as a cactus in a backyard pool. (Meg tells me they typically aren’t actually in the pool, but you know what I mean.) He went to high school in Scottsdale, a couple dozen miles northeast of Chase Field. After a stint at Yavapai Community College, he transferred to Arizona State to finish up his college career. Drafted by the Rays, Kelly shuttled off to Korea for four years in his 20s before returning to make his MLB debut for the Diamondbacks in 2019. He has spent his entire major league career in Arizona, save for a two month sojourn to Texas following a midseason trade at the 2025 deadline. Perhaps scandalized by Arlington’s complete lack of any public transit — not even a single bus line! — he kept his time with the Rangers short. In Phoenix, he’ll return as the presumptive ace at the unlikely age of 37 and with the unlikely fastball velocity of 91.8 mph.

There will be analysis of Kelly’s game to come, but his appeal is easily summarized: The guy can just pitch. Yes, his fastball sits about three ticks slower than the average right-handed pitcher. And sure, his stuff metrics are nothing to write home about. But even with these clear limitations, Kelly succeeds because he does two extremely important things: He locates the ball, and he makes it impossible for hitters to guess which pitch is coming.

The command bit is easy enough to see from his FanGraphs player page. Kelly’s 6.4% walk rate ranked in the 70th percentile among all pitchers with at least 80 innings pitched this season. Unlike many of his peers, Kelly cannot readily challenge hitters with fastballs over the heart of the plate in hitter’s counts. His stuff requires finesse, pitching on the edges, aiming for fine targets. Given these conditions, Kelly’s above-average walk rates are more impressive than they might seem at first glance.

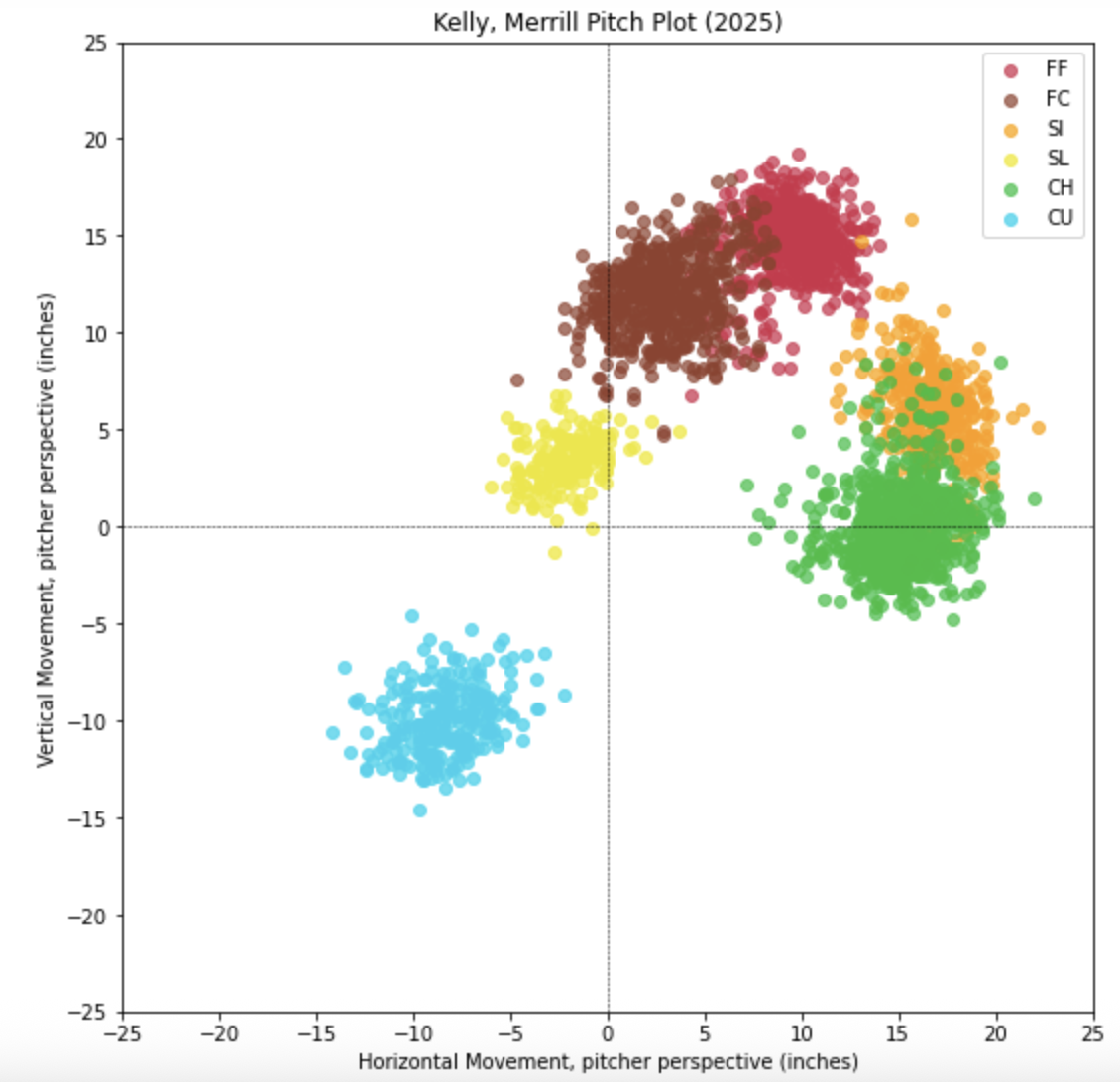

The unpredictability aspect requires more digging. As his pitch plot shows, Kelly throws three fastballs — a four-seamer , sinker, and cutter — all in the same quadrant:

Even the cutter moves arm side (and, it should be noted, performed spectacularly in 2025, allowing a .262 xwOBA on contact with equal usage to both righties and lefties). Kelly’s primary pitches — save for the changeup — all move in a similar tunnel.

He also mixes his pitches as well as anyone. To righties, he throws five pitches with nearly identical frequency. At 21% usage, his cutter is his most-used pitch to righties; at 19%, his sinker is his fourth most-used pitch. He leans more heavily on his changeup to lefties (more on that pitch later), but at 32% usage, he’s not exactly spamming it.

These tendencies make Baseball Prospectus’s arsenal metrics smile upon him. As a quick reminder, BP introduced these metrics in January of this year; they became available on the site’s leaderboards earlier this offseason. They grade a pitcher along four criteria: Movement Spread, Velocity Spread, Pitch Type Probability and Surprise Factor. While Kelly grades out poorly in the former two categories, he excels in the latter two. His pitch type probability — essentially, an average of how likely a hitter is to identify which pitch is coming — was 52.2%, 13th among the 274 pitchers with at least 1,000 pitches thrown. He’s exactly what you imagine from a slow-throwing veteran right-hander: a big pitch mix, and a willingness to throw any pitch in any count to any type of hitter.

Kelly’s unpredictability is the best explanation for his continued success at suppressing damage. Since 2022, he’s allowed just a .270 BABIP, ninth best among pitchers with 500 innings pitched over that period of time. These historical BABIP suppressing qualities make an argument for Kelly being a smidge better than his FIP-based WAR, which — outside of his injury-shortened 2024 — has finished between 3.1 and 3.2 each year of the aforementioned timeframe.

No analysis of Kelly can be complete without a discussion of his best pitch. Traditionally, the ideal changeup moves exactly like a pitcher’s four-seam fastball with as much velocity difference as possible. (This is what’s referred to as a “straight change.”) By these standards, Kelly’s changeup does everything wrong. He throws it over 88 mph on average, just three ticks slower than his heater, with almost 15 inches of difference in vertical movement. (Check out the gap between the red and green dots on the pitch plot above.) This power change — closer to a splitter by its movement characteristics — is nonetheless effective, racking up gaudy whiff rates (33.4% last year) even as Kelly throws it more than any other pitch.

As long as he’s healthy, Kelly has proven he can deliver above-average production even with subpar stuff, making the Diamondbacks’ $40 million bet a relatively safe one. Sure, he’s almost certainly not getting Cy Young votes, but he’s also nearly a lock to deliver a FIP in the high 3.00s or low 4.00s with a good chance of an even better ERA.

That will be just fine for the Diamondbacks, whose rotation depth was looking a little shaky after the departure of Zac Gallen in free agency. Even with the addition of Kelly (as well as Michael Soroka last week), Steamer still sees the team’s pitching as comfortably within the bottom 10. As a franchise, they are in a liminal state between Wild Card contender and rebuilder; if they ultimately decide to hold on to Ketel Marte and make a go of it, they are in need of as many reliable innings as they can get their hands on.

Their ability to meaningfully upgrade beyond Kelly, however, may be constrained by prior outlays. Corbin Burnes will be making $33 million to rehab his torn UCL for the majority of next season. Eduardo Rodriguez will make exactly as much as Kelly over the next two years, and posted an ERA over 5.00 in each of his two previous seasons in Arizona. Brandon Pfaadt is locked into a deal until 2030; while he certainly has upside, he’s yet to deliver an effective big league campaign. Even with Jordan Montgomery’s contract off the books, it’s hard to imagine them locking in another high-priced arm at a deal of considerable length, especially since even average-ish starting pitching is evidently going for big bucks on the open market. Kelly secured the second-biggest guarantee issued this offseason, trailing Dylan Cease’s $210 million by a solid margin. If Kelly’s contract is any indication, Michael King is likely to blow past his crowdsourced estimate of a $22 million AAV; Framber Valdez, Ranger Suárez, and Tatsuya Imai are all similarly licking their chops. With Ryne Nelson slotted in as a cheap and effective mid-rotation option and Kelly now in tow, the Diamondbacks rotation appears just about locked in.

Michael Rosen is a transportation researcher and the author of pitchplots.substack.com. He can be found on Twitter at @bymichaelrosen.

I’m the jerk that signed up to say “from whence” is redundant (like “as per”) since whence means “from where”.