Michael Wacha and All the Small Things

The Rays aren’t a mess at the moment, but at 9-8, they aren’t great, either. For an explanation, look no further than their starting rotation. Chris Archer is on the Injured List with a right forearm strain, Ryan Yarbrough has been BABIP’d to death, and veteran Rich Hill isn’t racking up strikeouts like he used to. Tyler Glasnow is doing, well, Glasnow things, but he alone can’t fix the Rays’ pitching woes.

It’s not as if the Rays are average by intent, though. They’d ideally have held onto Snell and Morton, but budgetary constraints led them to make odd transactions in hopes of remaining competitive. Trying to squeeze out one more quality year from Rich Hill? Definitely a Rays move. Bringing back Chris Archer? Ditto. So is signing… Michael Wacha?

One is unlike the others. There’s clear upside in Hill and Archer, but during the offseason, Wacha seemed like a run-of-the-mill option. He had a career-worst 6.62 ERA in 2020, and while his peripherals were better (a 5.25 FIP, a 4.30 xFIP, a 3.99 SIERA), they aren’t exactly admirable numbers. Yet, the Rays stuck with him. And after two rough starts, Wacha managed to shut out the Yankees over six frames with nine strikeouts last Friday.

Lucky? Maybe. The Yankees’ offense is struggling, after all. But the Michael Wacha of now is the result of a few refinements to his game. They aren’t as noticeable as Tyler Glasnow adding a slider, but they’re there, and I suppose someone needs to write about them.

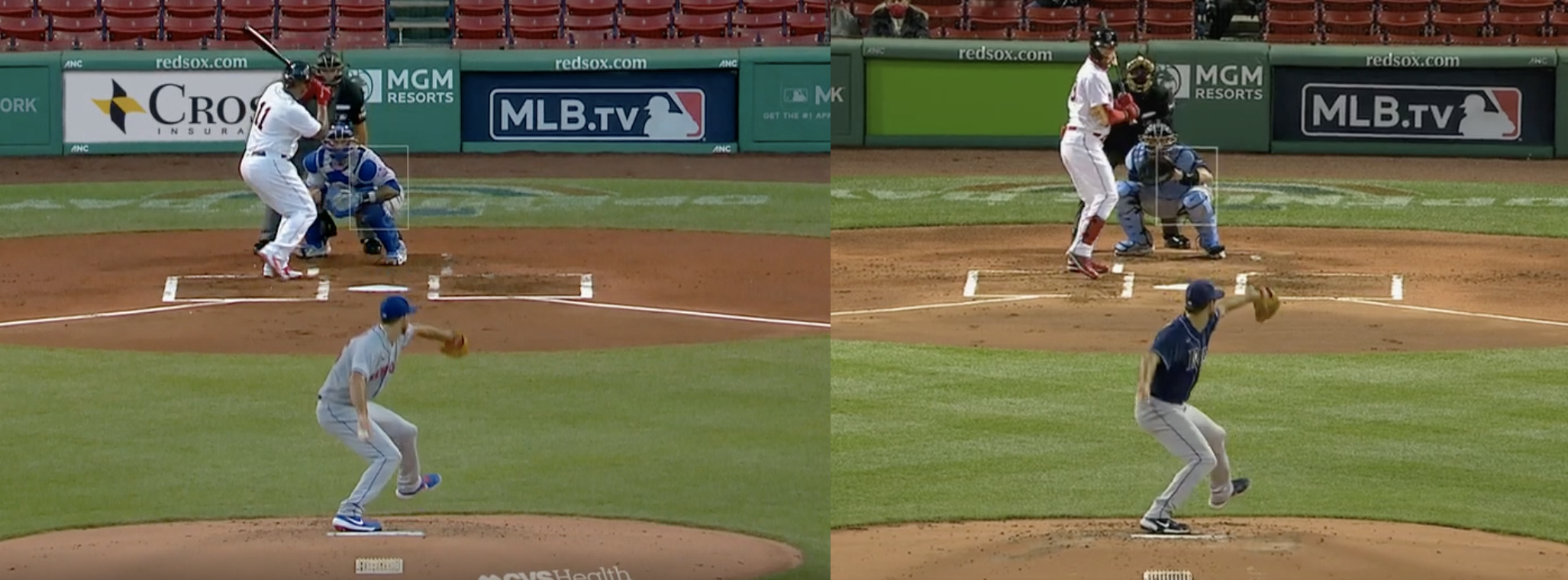

First, his delivery looks different. For consistency, both of these screenshots are from Wacha’s starts at Fenway Park. The left one is from 2020; the right one is from this season:

At roughly the same point in his delivery, Wacha now assumes a more upright posture. This alone, however, can’t tell us what he’s attempting to accomplish. Pitchers adjust their motions for a variety of reasons – achieving better balance, generating more velocity, and so on. Thankfully, the next pair of screenshots provide a better clue:

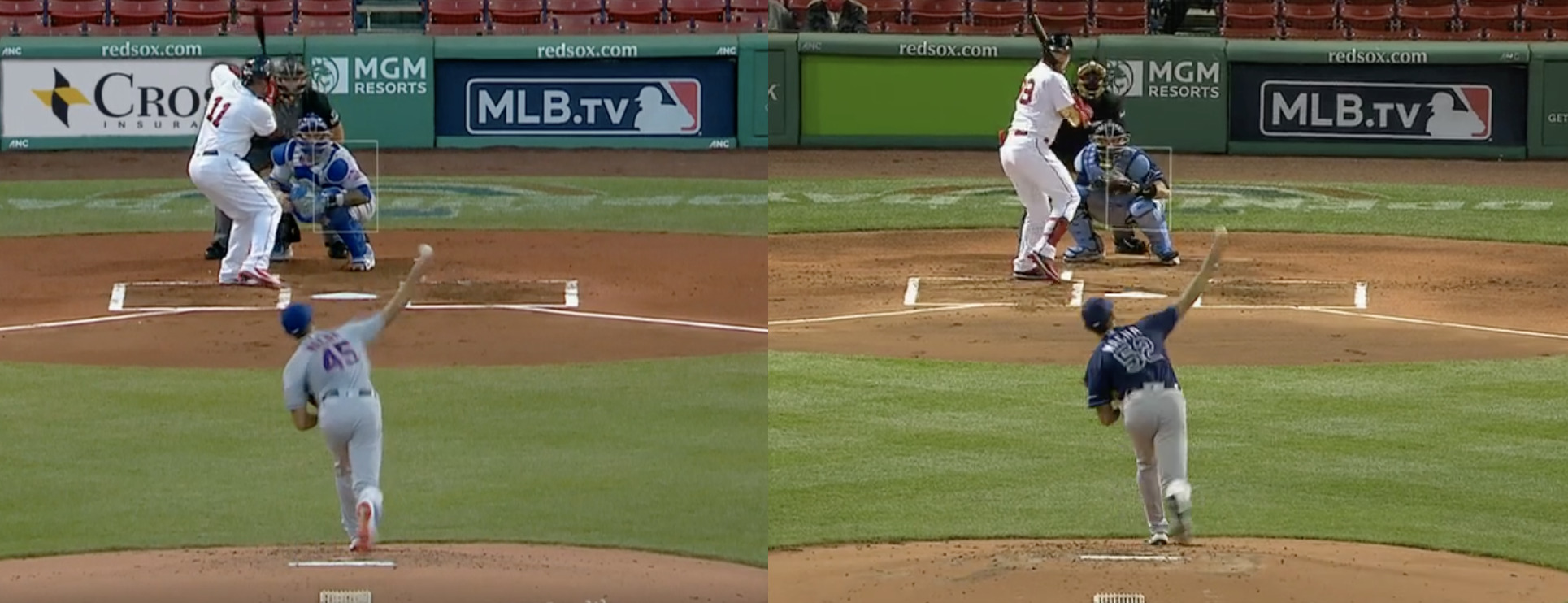

The difference is subtle, but it looks like Wacha has raised his release point. When I asked pitching coach Jeremy Maschino about this, he suggested that it could be related to his change in posture. That made sense. There’s no concrete relationship between the two actions, but I imagine it’s more difficult to generate the required momentum from his original crouch. Whatever makes the process of throwing higher in the zone replicable can only benefit Wacha.

As a result, all four pitches in Wacha’s repertoire – four-seam fastball, cutter, changeup, and curveball – have gained vertical movement this season. The biggest beneficiary is his fastball, which, according to Pitch Info, has added 1.2 inches of vertical break. Combine this increase with the high active spin rate it possesses (98% in 2020), and in theory, Wacha should see an uptick in whiffs by locating his fastballs up in the zone.

That’s not quite what’s happening, though. So far, Wacha’s fastballs have mostly ended up over the heart of the plate, a decision that’s resulted in a .414 wOBA against them. Maybe it’s an issue of command, not something Wacha or the Rays intend. But that’s not all. He’s also throwing fewer fastballs compared to last year, with cutters taking their place.

Initially, this confused me. Beginning in 2020, Wacha upped his cutter usage to remedy the fact that his four-seamer was unexceptional, both movement and velocity-wise. The problem, though, is that the cutter also isn’t spectacular! With 3.0 inches of vertical and 1.7 inches of horizontal break, the pitch suffered a bit from an identity crisis. I rise too little to be labeled a fastball-like cutter, but also break too little to be labeled a slider-like cutter. What am I?

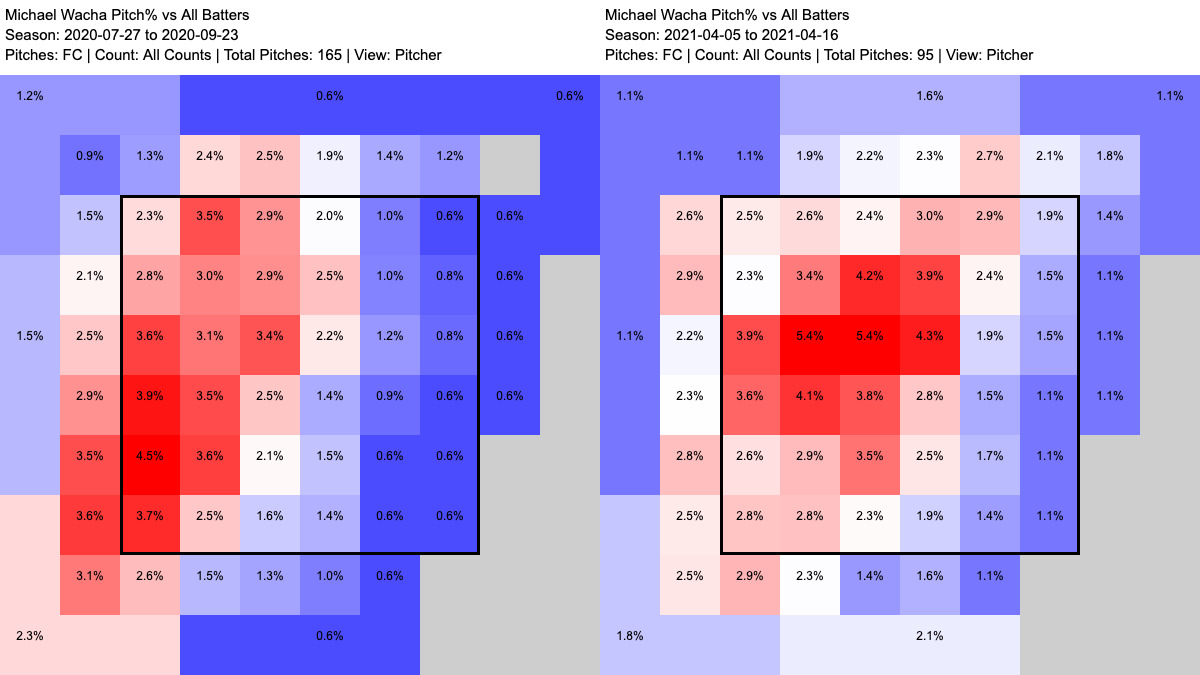

Turns out that this season, Wacha has made strides to solve the dilemma. A higher arm slot has boosted the vertical break of his cutter by 1.3 inches, but also, he’s locating it differently:

Last year, Wacha pretended that his cutter was a slider, which worked, I suppose – hitters had a .273 xwOBA against it – but might not have in the long-term. Now he’s locating it as if it’s a secondary fastball, up-and-in to lefty batters. Doing so allows Wacha to rely less on his regular fastball while taking advantage of the characteristics of his refined cutter. It’s still nothing too special, but it beats nothing at all. He’s escaped the no-man’s land of the cutter spectrum, so to speak.

Before taking a deep look at Wacha, I assumed he would bump up the usage of his changeup. It gets whiffs, hasn’t allowed an xwOBA over .300 even once in a season, and the Rays’ pitching philosophy is centered around maximizing one’s best pitch. Despite all that, Wacha’s changeup rate has decreased by 1.7 percentage points. What gives?

My educated guess: Because of how Wacha’s cutter complements it, he doesn’t need to throw the changeup more often for it to gain effectiveness. To elaborate, the cutter and changeup are separated by just 0.3 inches of vertical movement. But, by horizontal movement, there exists a whopping 9.4 inches of separation. Consider how that appears to hitters. The cutter and changeup initially travel along in near-unison, but they near home plate, the changeup veers away without warning.

Now, I’m no Pitching Ninja. I don’t know how to create pitch overlays. But the very least I can do is break down the tunneling effect via GIFs. Here’s a cutter that Wacha threw to Giancarlo Stanton:

Followed by a changeup:

And here’s a screenshot of the two pitches, side-by-side, before they diverged:

That’s nasty. Stanton didn’t bite at the changeup that Wacha set up with the cutter, but another hitter very well could have. Owing to how the changeup behaves, the cutter gains another dimension. It can function as a secondary fastball thrown up, but it can also live down in the zone when necessary. In fact, the now-versatile cutter had another moment in the same at-bat. After the changeup, Wacha went back to the cutter, but this time threw it where he usually does. A flummoxed Stanton barely fouled it off. With two strikes and a newly established height, Wacha was able to finish the job with a perfect high fastball:

Finally, there’s the matter of Wacha’s curveball, which he’s thrown 3.2% of the time so far to sneak in a strike or two in early counts. That seems like the best course of action. Its movement is too below-average to ever become an effective putaway pitch, but at the same time, abandoning it might reduce the unpredictability of Wacha’s repertoire. It’s nice to have a fourth option.

I know these aren’t the most exciting developments. Michael Wacha is no Aaron Civale abandoning his sinkers in favor of four-seam fastballs. But when we’re focused on the eye-catching shifts, we forget that for a majority of pitchers, small steps in the right direction are the norm. They too can be interesting, as long as we move beyond mere cursory looks. Wacha isn’t drastically different compared to his old self, but he’s added an inch or two of rise to his fastball, optimized his cutter, and continues to throw his stellar changeup.

The Rays don’t need Wacha to overhaul himself, anyways. For one year and $3 million, they looked to patch a hole in their starting rotation. As long as Wacha continues on his current path, he should fulfill that purpose – and possibly more.

Justin is an undergraduate student at Washington University in St. Louis studying statistics and writing.

Wacha’s cutter made an appearance in a table in Nicklaus Gaut’s piece on Seam Shifted Wake over on Rotographs. Essentially his cutter doesn’t break the way one would expect it to based on its spin – it’s one of the better ones in the majors in that regard and that’s desirable.

That’s a very good point, thanks.